Podcast: Escape from Warsaw’s Ghetto - Memories of a Child Witness

HALINA WOLLOH

LIMA, PERU

BORN 1936, POLAND

TRT: 17’11”

TOPICS:

LIFE IN WARSAW GHETTO

SAVED BY GRANDFATHER

ESCAPING GHETTO

REUNITING WITH FATHER

JOURNEY TO PERU

IDENTITY LOSS

TEACHING THE HOLOCAUST

SENSE OF PURPOSE

Escape from Warsaw’s Ghetto: Memories of a Child Witness

MUSIC FADE UP AND OUT

HALINA:

I have to tell my story, that’s why I survived. I’m here telling what I’m supposed to tell.

NARRATION:

Welcome to In Their Words: Surviving the Holocaust. Finding Hope, a podcast preserving the testimonies of those who survived the atrocities committed by the Nazis and their racist collaborators in the 1930s and 1940s, and who shared their stories at United Nations Holocaust commemorative events around the world, remind-ing us of the human cost of hate, and our responsibility to fight injustice. Some survivors have agreed to join us for an in-depth conversation. This is the story of Halina Wolloh.

Halina Wolloh and her parents arrived safely on the shores of South America in 1948 as Jewish refugees from their native Po-land.

The month-long voyage by boat from Italy’s Port of Genova was but one stretch of a lengthy journey from surviving the Warsaw Ghet-to, to eventual immigration to Peru.

Just a toddler when the Nazis stormed her family’s confining liv-ing quarters in the Warsaw Ghetto, Halina says the smell of fab-ric left a lingering reminder of the life-saving moment her grandfather hid her between textile goods, as women and children were piled into German trucks and taken to death camps.

Following her grandparents’ deportation, her father organized a successful escape from the Ghetto—one of many times their fate would be defined in an instant.

Speaking to us from her home in capital city Lima, Halina ex-plains how her family’s escape from persecution to safety was helped by demonstrations of humanity by the unsung heroes of the Holocaust — non-Jewish Europeans and other rescuers who risked their lives to protect Jews.

At 84 years old, Halina says fulfilling her purpose as a survivor means telling her story.

HALINA:

I was born in Warsaw Poland, in the year 1936. My full name is Halina Sachs-Stein and then “Wolloh”, once I was married.

NATALIE: If you could briefly describe your first years in Po-land, what was your childhood like?

HALINA: Well, I practically didn’t have a childhood unfortunate-ly because when I was four years old, the Second World War start-ed, the Nazis took my parents’ apartment and my grandparents’ apartment and put us in the ghetto.

Because I was young, I was four or five years old, what I can tell you is what my parents told me—the ones who saved my life.

NATALIE:

There was a moment when your grandfather hid you, correct? Could you tell us about that moment?

HALINA: Yes, my grandfather produced jackets and coats beginning several years before arriving to the ghetto, and thus has a lot of fabric in an attic. So the day the Nazis came in their trucks, he realized they came to take all the women and children that were working with the sewing machines, so my grandfather grabbed me, and shoved me between the fabric material, and this was how he saved me so the Germans couldn’t take me. So this was a life-saving moment.

NATALIE: Do you remember how you felt in that moment?

HALINA: I remember it by the smell of wool. You know that smells often make us remember. Even now, at 84, I just turned 84, every time I go into a fabric shop I remember that moment. It’s a part of my life you could say I will never forget.

Of course, life in the ghetto was very hard. They had us without food, without medicine, and there were no health workers. It was a very, very hard life. In 1942, the Nazis took my grandparents and my uncle to Treblinka.

After that, my father decided to organize an escape from the ghetto, and we did so. He taught us to pray “Our Father” in Polish. I speak perfect Polish until today. We escaped into the night, as Christians, and luckily, my father had a lot of non-Jewish friends in the Aryan part of Warsaw. He arranged to have each of us living in three separate non-Jewish homes—one for my mom, another for my father and another for me. I was taken care of by a friend of my father’s, a good woman who taught me to read and right. I was with her until 1945 when the war ended.

The Poles were ordered to turn in any Jew there was, so my par-ents couldn’t visit me much. They visited me maybe once every two months. This is how we saved ourselves.

When we had escaped and we lived in the Aryan area of Warsaw, my father was taken as a non-Jewish Polish prisoner in the streets. The Nazis arrested him, not realizing he was Jewish. Luckily, they didn’t kill him, but they did take him to work in forced la-bour in Berlin, in the Kruug factory, where they make Volkswagen automobiles and other brands of cars.

NARRATION:

When the war ended, Halina’s mother took her to live in a convent where she was cared for by nuns. At the end of 1945, the two set off for a new, temporary home out of the country.

HALINA: So then my mom and I left: An Italian woman who became my mom’s friend convinced my mother to take us to Italy. This was all happening in the year 1945, when the War ended. Well, my mother had already lost both parents and her older brother. She was sad and decided we would go to Italy.

NARRATION:

While living in Milan, Halina’s mother received letters from fam-ily in South America, encouraging her to move her family to join them in Peru.

She worked in a fashion boutique to support herself and her daughter. Meanwhile, a young Halina attended school at “Sebrino”, an institution for Jewish refugees and survivors of the War. It was on an outing for the children at Sebrino, that the portrait of Halina without her father and her mother without a husband, would change.

HALINA:

One Saturday or Sunday, I don’t remember exactly, but it was a day that the school organized an excursion through the city for us to explore the city of Milan by bus. I was there amongst the children, there were only a few of us sitting on the bus to visit the famous cathedral of Milan and the city. For a moment the bus stopped at an intersection. I looked out the window and saw my father. That was a miracle.

I jumped off the bus and told the driver he could go, I would stay with my father. Then, my father was consumed with joy, it was a big moment for him too. It was a life-changing moment.

NATALIE:

And how do you explain that?

HALINA:

You want me to tell you? We can’t explain that.

I think that was God’s will. I didn’t look for him, he didn’t look for me. It was a life-changing moment.

So I took him to where we were living, so he could see where my mom and I were. And the three of us stayed there, deciding what we would do next.

North American soldiers had freed my father. But when the war ended, he was without a job, it was a very tough situation for us in Italy then.

My mom showed my father all the letters she received from his family, talking about what a beautiful city Lima was, that Peru was a good country with good people and such. So, we remained in Milan for a couple of months, until my parents decided to make a trip.

NARRATION:

Embarking on a journey to a new life, on a a new continent, Ha-lina’s family of three set off on a ship from Italy’s port of Ge-nova, a month-long trip at sea before docking on the shores of Rio De Janeiro—just a pit stop en route to their final destina-tion. By land, air and sea, making stops in Bolivia’s La Paz and Peru’s southern pocket, until finally arriving in Lima. Halina was twelve, the year was 1948.

HALINA:

So we arrived in ’48, finally very happy, first of all because our lives were saved, and second, my father was happy because he was now with his brother. We settled in the neighborhood called “Miraflores”.

NATALIE:

At what point did you feel relief, did you feel “we are safe?”

HALINA: I think in Bolivia, in Italy too, but once we arrived in Bolivia it was a bit better.

NATALIE:

Because you were so far from Warsaw?

HALINA:

Yes. For my mom, it was a city she never wanted to see again. It was where they killed her parents and brother, so of course, she never wanted to set foot in Warsaw again. The fact that we got to Lima when we did, safe and sound, the three of us, was also a miracle. Coming out of the Holocaust was truly a miracle. My life in Peru have been my happiest years. First because I made many friends, I have two girlfriends who until today are my friends, and second because I met my husband in Lima. We fell in love, and we married in 1959. He was a civil engineer, we had three daugh-ters and six grandchildren.

NATALIE:

Congratulations. And how do you explain your surviving the Holo-caust, is there a special reason you feel you survived?

HALINA:

I think it was my destiny. It was my destiny in some way, with God’s grace, to survive those years, first in the Warsaw Ghetto, then the other countries I’ve passed through until finally arriv-ing in this one. And I believe this is really a marvelous coun-try. Until today I have a lot of love for Peru, and I feel very identified with the country—far more than I do with Poland.

NATALIE:

Have you ever returned to Poland?

HALINA: No, I never wanted to go back. I have a somewhat serious problem with Poland. I have three daughters and six grandchil-dren. I wanted to obtain my Polish citizenship and Poland has de-nied me. It has been a great injustice. I speak perfect Polish, but don’t have a single document because everything was burned in the ghetto.

I think at some point Poland will realize that everything I’ve told them is the honest truth and they have committed a serious injustice towards me.

NATALIE:

With history as it is, one would think this is a problem for many people who left Poland?

HALINA: Yes, but every child, each of us who have survived this Holocaust, this terrible war, we each have our own story.

NATALIE:

We’ve invited you and other survivors to share their testimonies on this podcast to be able to share and preserve your stories. Why do you think this is important?

HALINA:

First of all, so it won’t happen again. It was a terrible geno-cide. The Holocaust needs to be a studied subject, schools must recognize what happened and the fundamental reason is so it won’t happen again. Because six million people—men, women, children died. That’s the important part.

And the United Nations should also play a part in educating youth who don’t know what happened. We survived, and I think it’s to share what happened, to tell the story. I’ve been very lucky I didn’t have to go to a concentration camp, because we escaped.

NATALIE:

You participated in a commemorative event with the United Na-tions, what did that mean for you, how did it feel?

HALINA:

Well I felt extremely honoured. They invited me, I told my story, everything that happened to me and my family. I have to tell my story, that’s why I survived. I’m here telling what I’m supposed to tell.

NATALIE:

Halina thank you very much for sharing with us today.

HALINA:

I thank you for the interview. Take care.

NATALIE:

Take care.

NARRATION:

You’ve just heard from Halina Wolloh, who along with her parents, survived the Holocaust through escape, and with the help of non-Jewish families credited with taking them in. This is In Their Words: Surviving the Holocaust. Finding Hope, a podcast by the United Nations Outreach Programme on the Holocaust. You can visit www.un.org/en/holocaustrememberance to find out more about the Organization’s Holocaust remembrance and education programme, and how you can participate. I’m Natalie Hutchison. Thanks for lis-tening.

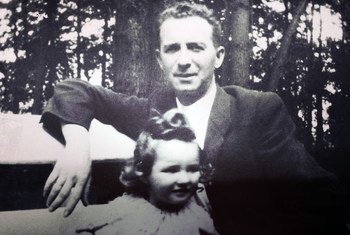

When Halina Wolloh was four, her grandfather hid her from the Nazi regime – behind a stack of textiles.

When her father decided to move the family from the Warsaw Ghetto, she learned The Lord’s Prayer in Polish, in case her identity was questioned.

As a young woman, she lived for years with her Jewish identity invisible to the world, finding refuge in the homes of non-Jewish Europeans in Poland, until finding safety across oceans.

Today, the 84-year-old mother of three and grandmother to six lives in Peru, where she and her parents arrived more than seven decades ago.

Having previously participated in a UN Holocaust remembrance event, Mrs. Wolloh sat down with Natalie Hutchison to detail her testimony in this edition of In Their Words: Surviving the Holocaust. Finding Hope about how, even in the darkest of times, expressions of humanity emerge.

PRODUCTION NOTES:

English voice over: Ana María Chávez

Music Credit: Ketsa

-

We are Stardust

-

Soul Sale

-

The Stork

-

Ones Left Behind

-

Empty Playground