UN: cholera outbreaks can be controlled thanks to vaccines, water and sanitation

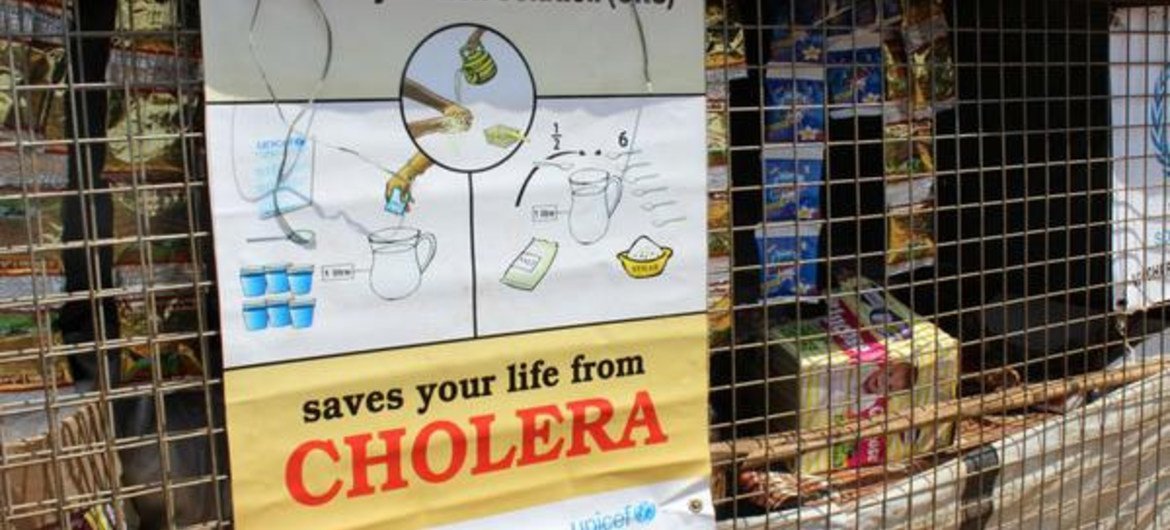

The use of Oral Cholera Vaccines (OCV) must be both supported by local authorities and used hand-in-hand with focused, sustainable water and sanitation actions in targeted communities, the agency recommends in a press release.

A global stockpile of vaccines, funded by a number of international organizations and foundations, initially made 2 million doses of the vaccine available. In 2015, with additional funding from the GAVI Alliance, the number of doses available for use in both endemic hotspots and emergency situations is expected to rise to around 3 million.

There are several examples in which the vaccine has stopped cholera outbreaks in their tracks, such as in South Sudan in 2014, when thousands of displaced people who had found shelter in makeshift camps at UN sites were given the vaccine. This action almost certainly averted increased illness and death among the vulnerable camp inhabitants who had been at high risk, WHO noted.

But new outbreaks are ongoing in South Sudan and Tanzania, fanned by insecurity and additional displacement. Intensive control efforts are ongoing, and vaccination programmes have been rolled out to target communities at risk. In conflict-wracked Yemen and earthquake-ravaged Nepal, WHO has been working with national authorities and partners on the ground to prepare for any outbreak of cholera, as well as acute watery diarrhoea.

Cholera, according to WHO, is an acute intestinal infection caused by ingestion of food or water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. It has a short incubation period, from less than one day to five days, and produces an enterotoxin that causes copious, watery diarrhoea; vomiting also occurs in most patients. Cholera can quickly lead to severe dehydration and death without prompt treatment.

The WHO-led Global Task Force on Cholera Control aims to end cholera deaths by strengthening international collaboration and increasing coordination among partners in three of the main situations where cholera circulates.

The first is in endemic conditions, where the disease is entrenched in communities, such as in some regions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sudden outbreaks are another scenario, where an instant vaccination response is deemed most effective, such as in Guinea and Malawi. Finally, cholera can be a consequence of a humanitarian crisis, as it was the case in South Sudan in 2013, or in the recent outbreak in Tanzania when thousands of people displaced by fighting in neighbouring Burundi were successfully vaccinated against the disease.

Effectively controlling a disease means reducing new cases in defined locations to zero through targeted efforts, WHO emphasized. In the case of cholera, these include the use of oral cholera vaccine, improving water and sanitation practices, engaging the community in implementation of control measures, and sustaining control efforts to prevent its re-emergence.