Character Sketches: U Thant by Brian Urquhart

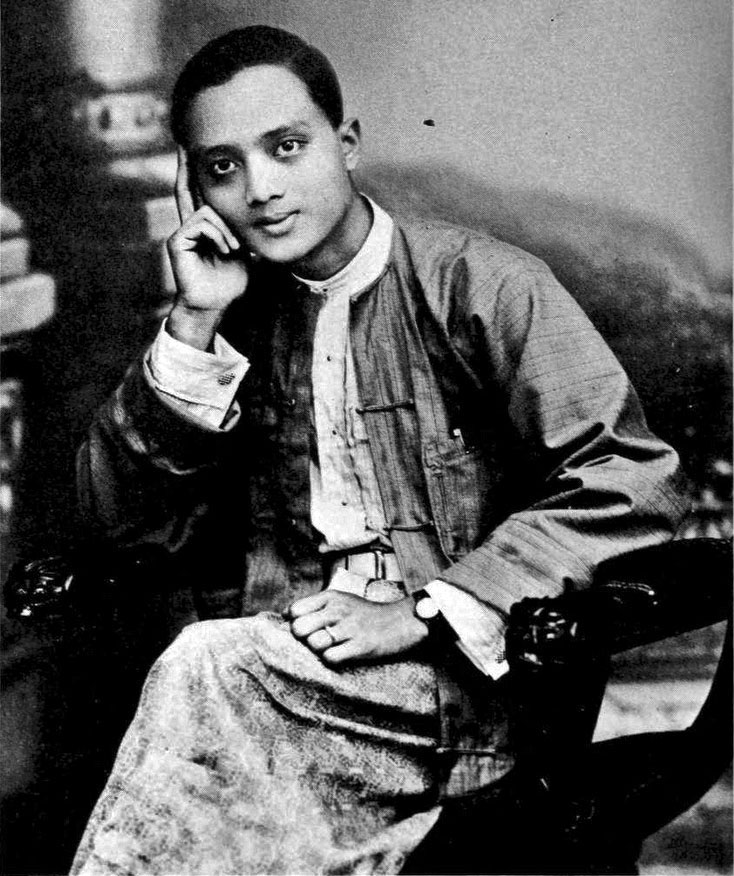

U Thant, the third Secretary-General of the United Nations, was a devout Buddhist, a very private man who suddenly found himself in one of the most public and exposed jobs in the world. When Dag Hammarskjöld died in an air crash in Africa in September 1961, U Thant was designated by the Security Council to complete his term as Secretary-General.

It was a catastrophic moment in the UN’s history. The crisis in the Congo had caused the Soviet Union and France to challenge the authority of the Secretary-General in a way that threatened to bring UN peacekeeping operations to a halt. The organization was split down the middle on Cold War lines, as well as being bogged down in a violent and frustrating mission in the heart of Africa. U Thant pulled the UN together and brought it back onto a steady course in a time of storm and change.

When U Thant became Secretary-General, I was in charge of the UN operation in Katanga, a difficult and sometimes dangerous job. Having been kidnapped and badly beaten up on the evening of my arrival in Elisabethville, I was obligated to unleash the UN forces to stop a new wave of attacks and harassment on UN personnel. I was tired, short-handed, and exasperated by the disunity and incompetence of the military organization I had to work with.

In this dismal scene, the whole-hearted and unequivocal support of the new Secretary-General in New York was encouraging. Not only did U Thant work hard to get us military reinforcements; he also took the offensive with the Western media, which, under the influence of Katanga’s expert public relations organization, had tended to favor Moise Tshombe, the secessionist president. To the distress of his right-wing and business supporters in the United States and Europe, U Thant even called Tshombe and his associates a “bunch of clowns.” This outspokenness at the top was refreshing, particularly when so much seemed to be going wrong in the field.

I met U Thant for the first time when I got back to New York from Katanga in the spring of 1962. He was friendly, informal, and genuinely interested in what one had to say -- in contrast to Hammarskjöld, who paid little heed to subordinates. U Thant also differed from his predecessor in more fundamental ways. He was simple and direct where Hammarskjöld was complicated and nuanced; a man of few words where Hammarskjöld was immensely articulate; a devout traditional Buddhist where Hammarskjöld was increasingly inclined to a personal brand of mysticism; a man of imperturbable calm where Hammarskjöld could be highly emotional; a modest and unpretentious middlebrow where Hammarskjöld was intensely intellectual; a taker of advice where Hammarskjöld almost invariably stuck to his own opinion.

To the casual observer, U Thant appeared placid and rather bland, but he was determined and courageous in his quiet way. He was totally free of the desire to take credit, to justify himself, or to blame others when things went wrong. His Buddhist self-discipline concealed the irritation and frustration that anyone else in his position would often have given vent to. He never lost his temper or showed impatience. In moments of unusual stress he would tap his foot rhythmically, his only display of emotion. He was a martyr to ulcers and various stress ailments in later years.

I doubt if most diplomats, especially from the West, really understood U Thant, for whom moral and ethical considerations took priority over political ones. He did what he believed to be right, even when it was politically disadvantageous for him to do so. U Thant regarded the war in Viet Nam as a moral and to some extent a racial issue, and was appalled at its almost casual toll of Vietnamese as well as American lives. He doggedly pursued his efforts to find a way to end the war long after a resentful U.S. Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, had rejected his plan for a cease-fire in place and peace talks in Rangoon, to which the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong had agreed. Rusk, in a vulgar and snide public statement, said that U Thant’s efforts to end the war in Viet Nam were motivated by his desire for the Nobel Peace Prize. This malicious and deliberate misreading of U Thant’s motives was made even more grotesque by the subsequent horrors of the war. Three years and hundreds of thousands of casualties later, Henry Kissinger took up, with some success, U Thant’s basic approach for seeking an end to the war.

U Thant lived a simple family life, going home each evening to his wife in Riverdale to read official papers as well as a score of newspapers and journals. He had no interest in the social and artistic life of New York, and hostesses and ambassadors alike gave up inviting him to dinner. He refused the Shah of Iran’s invitation to his grotesquely lavish international party at Persepolis on the grounds that, with so much poverty and misery in the world, he would not feel comfortable at such an occasion.

A look back at some of the highlights of the career of U Thant, the third Secretary-General of the United Nations. Credit: UN News

When international peace was threatened, U Thant was ready. At the start of the Cuban Missile crisis in 1962, he wrote to Kennedy and Khrushchev saying that he was sure that neither would wish to be remembered by history, if any history survived, as having jointly precipitated the end of human civilization. He then proposed actions -- the US calling off the naval quarantine of the Soviet vessels in the Atlantic, and the Soviets turning round the missile convoys and removing their missiles from Cuba -- by which both could back away from catastrophe.

He thus provided a face-saving mechanism, a ladder down which the two superpowers could, and eventually did, descend from their potentially catastrophic confrontation. He then went to Cuba to calm down an angry and resentful Castro. He did not make his efforts public and in his lifetime he received no credit for them.

In September 1965, after U Thant had been warning the Security Council of the danger for the preceding six months, full-scale war over Kashmir broke out between India and Pakistan. The close involvement of the Soviet Union with India, and, of China with Pakistan, made this conflict more dangerous than an ordinary regional war, and the Security Council belatedly sprang into action, asking the Secretary-General to tackle the situation urgently. U Thant set off the war zone at once and took me with him.

The Secretary-General usually travels by commercial airline, but all commercial flights to the subcontinent had been cancelled because of the war. President Lyndon Johnson offered Air Force One, but U Thant did not want to be so dramatically identified with the United States, and told Johnson that he would feel foolish traveling with a party of four in so large a plane. We flew commercial from New York to Tehran, hoping from there to find some way of getting on to Rawalpindi, our first destination.

In Tehran, everyone except U Thant seemed obsessed with the Secretary-General’s safety in a war zone. (Hammarskjöld’s death in Africa was still very much in people’s minds.) Because the Indian Air Force had bombed both airfields, it was widely believed that it would be too dangerous to land at Karachi or Rawalpindi. U Thant simply said that he had to get to the war zone as soon as possible by the best means available. The American embassy in Tehran, which was better informed and better equipped than we were, offered a small plane, the Convair of the US Air Attaché, and we quickly took off for Pakistan.

Highlights from U Thant's UN service

14 August 1957 – Before entering international diplomacy, U Thant’s experience was centred on education and information in his home country of Burma, as Myanmar was then known. Between 1957 and 1961, he served as Burma’s ambassador to the United Nations. During that period, he headed Burmese delegations to the sessions of the General Assembly, and served on various UN bodies. Shown here, at UN Headquarters in New York, Ambassador Thant (right), soon after his appointment as Burma’s new Permanent Representative to the world body, presents his credentials to Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld – the man he was to succeed as head of the UN in sad circumstances some four years later. UN Photo

03 November 1961 – Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld was killed in a plane crash while on a peace mission in Africa. The UN General Assembly voted on a draft resolution to appoint Ambassador U Thant as Acting Secretary-General for a term of office, extended until 10 April 1963 – the result of a unanimous vote by the General Assembly, on the recommendation of the Security Council, to fill the unexpired term of the Mr. Hammarskjöld. In total, U Thant went on to serve as the world body’s head from 1961 to 1971. Shown here, Ambassador U Thant is administered the oath of office by the General Assembly’s then-President, Mongi Slim of Tunisia, in the Assembly’s hall. UN Photo

16 November 1961 – One of the most immediate issues facing Acting Secretary-General U Thant was the situation in the Republic of the Congo (now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo), which became independent in May 1960, after many decades as a Belgian colony. Soon after independence, it experienced political upheaval, a secessionist movement and civil war. Shown here, the Acting Secretary-General takes part in a Security Council meeting on the Congo. Those seated behind him include the Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs, Ralph J. Bunche, and the UN Representative in the Congo-Elizabethville, Dr. Connor Cruise O'Brien. UN Photo

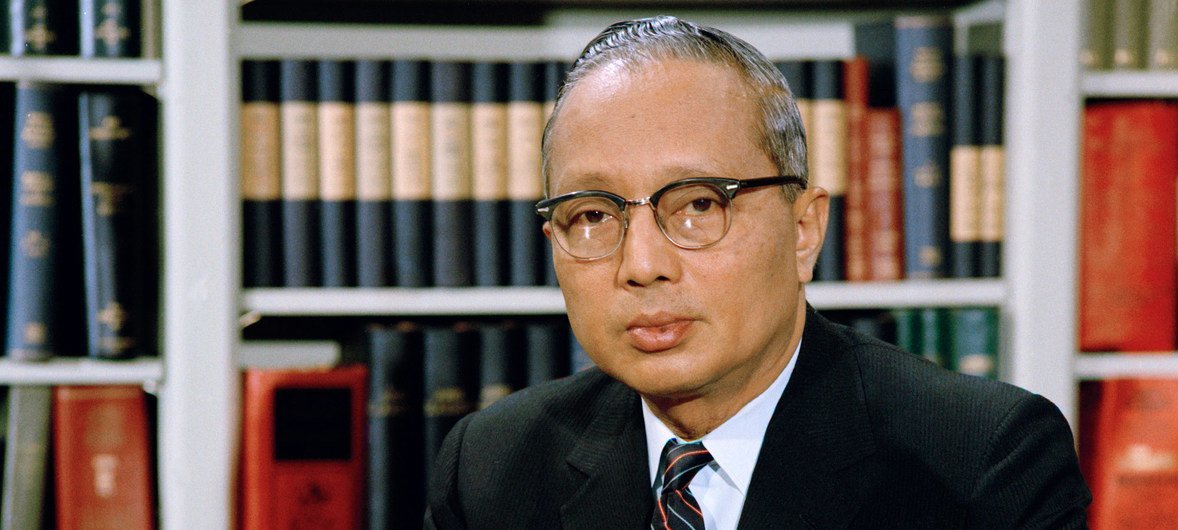

24 November 1961 – The idea of preventive diplomacy has captivated the United Nations ever since it was first articulated by Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld nearly half a century ago. According to former UN staffer and academic Bertrand G. Ramcharan, Mr. Hammarskjöld knew that the United Nations could do little where there was a direct clash of interests between the superpowers during the Cold War. But he had in mind that, if the opportunity presented itself, he might be able to head off disputes between lesser powers and prevent them from the gravitational pull of the superpowers' contest. Mr. Ramcharan has noted that as Secretary-General, U Thant moved Hammarskjöld's vision forward, with his role in preventing a nuclear confrontation over the Cuban Missile Crisis often ranked as the most spectacular example of preventive diplomacy in the annals of the world body. Shown here, Acting Secretary-General U Thant at his desk at UN Headquarters in New York. UN Photo

31 October 1962 – One of the most pressing new issues to arise on the international community’s agenda was the Cuban missile Crisis, which many historians have described as one of the most dangerous periods in human history, when the world came closest to blowing itself up during thirteen days, from 16 to 28 October 1962. The efforts of Acting Secretary-General U Thant, who used a preventive diplomacy approach, contributed greatly to defusing the crisis. Shown here, the UN chief shortly after landing in New York City in the wake of a visit to Cuba, where he held a series of talks with Prime Minister Fidel Castro regarding the crisis. UN Photo

26 November 1962 – During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Acting Secretary-General U Thant stressed that what was at stake was the very fate of mankind. He called for urgent negotiations between the parties directly involved and informed the Council that he had sent urgent appeals to the leaders of the United States and Soviet Union for a moratorium of two to three weeks. He also offered to make himself available to all parties concerned for whatever services he might be able to perform. Shown here, the UN chief confers with the Soviet Union’s Deputy Premier, Anastas I. Mikoyan, and others as talks amidst talks at UN Headquarters on unsettled phases of the Cuban situation. As an agreement was being worked out, US President John F. Kennedy, in a letter to the Soviet Union’s Premier Nikita Khrushchev, on 28 October 1962, said: "The distinguished efforts of Acting Secretary-General U Thant have greatly facilitated both our tasks." When the crisis was finally over, the US and Soviet negotiators sent a joint letter to the UN chief which said: "On behalf of the Government of the United States of America and the Soviet Union, we desire to express to you our appreciation for your efforts in assisting our Governments to avert the serious threat to peace which arose in the Caribbean area." UN Photo

04 August 1963 – In November 1962, U Thant was unanimously appointed Secretary-General by the General Assembly for a term of office ending on 3 November 1966. Shown here, Secretary-General Thant meets with the Soviet Union’s Premier Nikita Khrushchev and other officials, ahead of the signing of the historic Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty by representatives of the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States, in Moscow. UN Photo

16 October 1963 – Space was not on the UN’s agenda in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War – but that soon changed. The Space Age kicked off in October 1957, with the launch of Sputnik 1, mankind’s first artificial satellite, launched by the Soviet Union. The United Nations recognized that outer space added a new dimension to humanity's existence and, in 1958, took the first steps towards the peaceful, orderly and international development of outer space. The first man and woman in space – Soviet cosmonauts Yuri Gagarin and Valentina Tereshkova – were guests of Secretary-General U Thant when they visited UN Headquarters. Shown here, the UN chief presents them with albums of UN stamps and autographed copies of photographs taken earlier that day. UN Photo

16 December 1963 – When the United Nations was established in 1945, 750 million people – almost a third of the world's population – lived in territories that were non-self-governing, dependent on colonial powers. Today, fewer than two million people live in such territories, with the 1960s seeing many countries, especially in Africa and Asia, shed their colonial status and become independent states, with UN support. Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant and other officials watch as the flags of Zanzibar and Kenya were added to the 111 flags already flying in front of UN Headquarters, following an earlier General Assembly meeting that day, at which UN Member States admitted the two countries as the Organization’s 112th and 113th members. UN Photo

17 December 1963 – The Viet Nam War was to provide a challenge for international community, with Secretary-General U Thant voicing his opposition to the continuation of the conflict. Shown here, Secretary-General Thant with US President Lyndon B. Johnson, during the latter’s visit to UN Headquarters, during which he also addressed the delegates to the eighteenth session of the General Assembly. "In order to bring peace to Viet Nam, to find an enduring peace for that very unfortunate country, its independence and non-alignment should be the objectives of all parties primarily concerned with the conflict," he was to say about the war some years later. UN Photo

25 July 1964 – Secretary-General U Thant’s travels also included a visit to his homeland, at the invitation of the Burmese Government. While there he exchanged views with General Ne Win and others, spent some time with his family and paid homage at the great Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon (then known as Rangoon), as shown here, accompanied by his 81-year-old mother (on his left). It was his second visit to Rangoon since he left the country seven years earlier and his first as Secretary-General. UN Photo

26 June 1965 – The year 1965 was the twentieth anniversary of the signing of the UN Charter in the eastern US city of San Francisco. Local universities and colleges commemorated the occasion, as well as the International Cooperation Year, and invited Secretary-General Thant and top UN official Ralph J. Bunche to attend a celebration at the University of California, Berkeley. Shown here, the two UN officials confer while at the event. UN Photo

9 June 1967 – The Six-Day War between Israel and neighbouring countries Egypt, Jordan and Syria began in early June, drawing the international community's attention. Shown here, during a General Assembly debate on a letter from Soviet Union authorities on the situation in the Middle East, UN officials - including Secretary-General U Thant - watch as the Foreign Minister of Israel, Abba Eban, addresses UN Member State representatives. UN Photo

24 October 1971 – United Nations Day, which falls on 24 October, marks the anniversary of the entry into force in 1945 of the UN Charter. With the ratification of this founding document by the majority of its signatories, including the five permanent members of the Security Council, the United Nations officially came into being. The day has been celebrated since 1948. Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant leaves the podium at the General Assembly hall after a speech and presenting the UN Peace Medal to Spanish cellist and conductor Pablo Casals (centre), who had composed a new composition for the day. UN Photo

06 December 1971 – Secretary-General Thant retired at the end of his second term as Secretary-General, in late December 1971. Shown here, the UN chief is greeted by a security officer as he returns to work at UN Headquarters, shortly before his retirement, after having been hospitalized for a number of weeks for the treatment of an ulcer condition. The ensuing years were to see him undergo several operations for cancer. UN Photo

27 November 1974 – After his retirement as Secretary-General, U Thant spent the last years of his life promoting the development of the global community and other issues he had advocated for while serving the United Nations. He died from lung cancer at the age of 65 on 25 November 1974. Before being flown back to Burma (now known as Myanmar), his body was brought to UN Headquarters to lie in state for 24 hours so that friends and relatives, members of delegations, colleagues, the media and the general public could pay their last respects. UN Photo

23 May 2008 – U Thant was a Buddhist by belief. According to the New York Times, he once said, “I have been trying to concentrate, to contemplate, to mediate and to eliminate all hatred, all anger, all bitterness from my being, to detach myself from mundane things and to achieve emotional equilibrium. Of course, it is very difficult to achieve. But this is my way of life.” His remains were flown back to Burma (now known as Myanmar), where it was subsequently given a traditional Buddhist burial. Shown here, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon pays tribute to his predecessor during a visit to his memorial the city of Yangon. UN Photo

The Convair was very slow, and because both the Indians and the Pakistanis believed that the crew were in the CIA, our journey was subject to long detours and delays. We eventually arrived in Rawalpindi to see the President, Ayub Khan, and then, after an immense detour around the fighting zone via Bombay, in New Delhi to talk to Prime Minister Shastri. We came back with the basis for a cease-fire, which came into effect two days later.

This expedition increased my respect and affection for U Thant. His wisdom and steadiness impressed and calmed over-excited leaders distracted by wartime emotions. He left the drafting of proposals and communiqués to me, and took full responsibility for them. I also found that U Thant was a keen observer who took great pleasure in the comic aspects of such a mission. Unbeknownst to him, Burmese officials along the route had been notified of his wife’s fondness for mango jam, and at every stop consignments of this explosive substance had been put on board our plane. When some of the jars began to hiss and tick, the captain declared a bomb alert and threw the whole lot out. This was the first time that I saw U Thant overcome by laughter.

U Thant particularly relied on Ralph Bunche. As Bunche’s health was rapidly declining, I met with U Thant increasingly often on day-to-day matters. I also wrote most of his political speeches and reports. He was delightful to work with, and his straightforwardness and decency easily made up for a certain naiveté in political matters. He and his wife set much store by astrology, which occasionally created scheduling difficulties when his wife pronounced certain days unpropitious for important actions. When our son Charlie was born in 1967, U Thant spent an evening making out his astrological chart. He was astonishingly thoughtful of his subordinates.

In June 1967, President Nasser of Egypt suddenly demanded the withdrawal of the UN peacekeeping force in Sinai (UNEF) that had kept the peace between Israel and Egypt for the previous ten years. Nasser had a perfect right to do this under the agreement that he had made with Hammarskjöld before the force first arrived in Egypt ten years earlier, and U Thant was bound by that agreement. (Israel had never allowed UNEF to be stationed on Israeli soil at all.) Nasser’s demand was a suicidal move for Egypt, because it gave Israel the long-desired pretext to move into Sinai and Gaza, and, if Jordan and Syria were foolish enough to join in the Egyptian action, to take East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights as well. U Thant and Bunche spent much time and energy trying to alert Nasser to the huge risk he was running.

Alone among world statesmen, U Thant went to Cairo to try to persuade Nasser to withdraw his troops from Sinai and to cancel his demand for the departure of UNEF. Other leaders gave priority to Cold War matters and, in Western countries, to denouncing U Thant for being willing even to consider Nasser’s request for the withdrawal of UNEF, though he was legally bound to do so. No government supported U Thant’s efforts with Nasser, and on 5 June, the Israelis launched simultaneous air attacks on Egypt, Syria and the Jordanian troops in the West Bank. UNEF was still in place, and its soldiers suffered the first casualties of the war.

The Six-Day War was a major disaster for the Palestinians and for the Arab countries, and also for the UN. It created problems - Israeli occupation of the West Bank, Gaza and the Golan Heights -- that the world is still trying to resolve. In the Security Council the great powers of the East and West did little but bicker along Cold War lines until the war actually started. For such a major catastrophe governments and the press needed a scapegoat, and they selected U Thant, the one person who had tried so hard to prevent it.

Meetings and encounters

In all my time in the UN I can recall no injustice to a public figure remotely comparable to the treatment of U Thant. For a time it was impossible to get any serious public consideration of the actual facts of the case. Fashionable American columnists, and even national leaders who should have, and did, know better, had a field day denouncing U Thant. Israel’s ambassador, Abba Eban, referred to UNEF as “an umbrella that folds up when it starts to rain” -- a remarkably cheap piece of rhetoric considering that in spite of Israel’s refusal to cooperate with UNEF, we had for ten years kept Israel’s formerly bloody boundary with Egypt completely peaceful. U Thant never complained, though we occasionally persuaded him to hit back publicly against some more than usually grotesque distortions, such as the serialized memoirs of the former British Foreign Secretary, George Brown.

10 November 1961 – The work of a UN Secretary-General involves interacting with a range of people – from those most in need to those making decisions which affect those most in need. It was no different for U Thant during his two terms at the helm of the world body. Shown here, the UN chief welcomes the Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, who delivered a speech to a plenary meeting of the General Assembly at UN Headquarters. UN Photo

23 October 1962 – Shown here, Acting Secretary-General U Thant greets Crown Prince Hasan Al-Rida Al-Sanusi of Libya, during the latter’s visit to UN Headquarters UN Photo

20 September 1963 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant bids farewell to the President of the United States of America, John F. Kennedy, during an official visit to UN Headquarters, during which the US leader also addressed delegates to the 18th session of the General Assembly. UN Photo

28 January 1964 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant watches as the US Attorney General, Robert F. Kennedy, shakes with the Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs, Ralph Bunche, a long-serving UN official who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950 for his work in the Middle East. Mr. Kennedy had just returned from his visit to Asia where he held discussions with the leaders of Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. UN Photo

21 April 1964 – Sketches of the former Secretaries-General – Trygve Lie and Dag Hammarskjöld – and then-serving UN chief U Thant, done by US artists Helen Honchs, were presented to the UN Correspondents Association Club at UN Headquarters. Both living officials attended the event. Shown here, the first and third Secretaries-General confer shortly after the presentation, in front of one of the sketches. UN Photo

25 April 1964 – It is not always a case of meeting officials and dignitaries on subjects of geopolitical importance for UN chiefs. Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant with children at the opening of the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair. UN Photo

21 July 1964 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant outside the Elysee Palace in the French capital, Paris, where he met with the President of France, General Charles de Gaulle (centre). UN Photo

24 June 1966 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant escorts the King of Saudi Arabia, Faisal Bin Abdul Aziz, out of the UN Headquarters complex following an official visit by the Middle Eastern royal. UN Photo

21 September 1966 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant greets the President of the Philippines, Ferdinand E. Marcos, during the latter’s visit to UN Headquarters, during which he also addressed the General Assembly. UN Photo

10 April 1967 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant confers with the Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, at her residence, during a visit to the Indian capital of New Delhi. The UN chief was paying official visits to – at the invitation of the respective governments – Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), India, Nepal, Afghanistan and Pakistan, for meetings with their leaders. UN Photo

24 May 1967 – Tensions in the Middle East were high in the lead-up to the Six-Day War – which took place in early June 1967 – between Israel and neighbouring countries. It included long-running factors, as well as short-term issues such as border clashes and a blockade of access to the sea. Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant converses with the President of the United Arab Republic, Gamal Abdel Nasser, while on a visit to Cairo. Egypt – as the United Arab Republic waas then known – was one of the countries involved in the conflict. UN Photo

09 June 1967 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant escorts Thailand's King Bhumibol Adulyadej and Queen Sirikit out of the building following a visit to UN Headquarters. UN Photo

21 October 1967 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant with Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (second from left) and other officials from the South-East Asian country. UN Photo

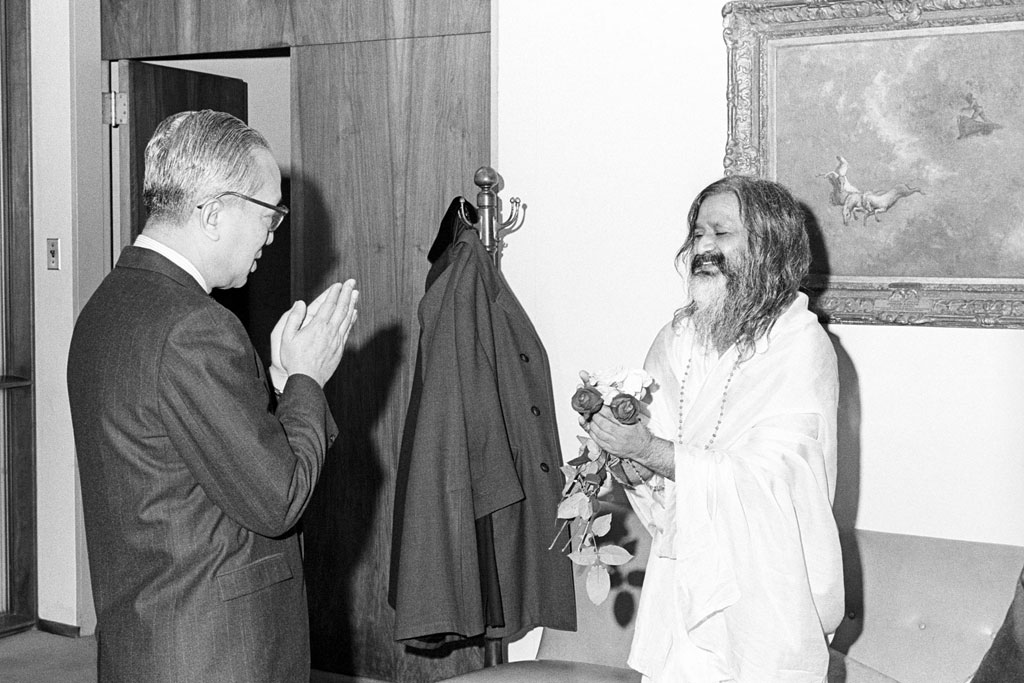

20 January 1968 – Shown here, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, an advocate for transcendental meditation, meets with Secretary-General U thant during a visit to UN Headquarters. UN Photo

22 April 1968 – Shown here, Secretary-General Thant is accompanied by the Shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlevi, and his wife, at the International Conference on Human Rights, the first such world-wide meeting organized under UN auspices, which took place in the Iranian capital of Tehran. UN Photo

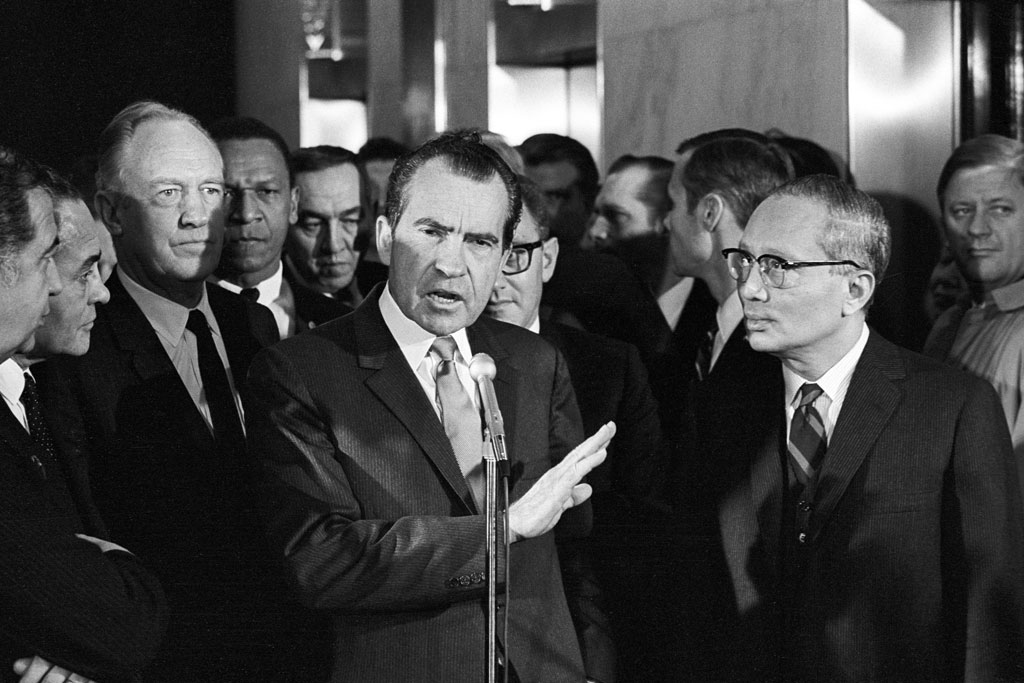

17 December 1968 – Shown here, US President-elect Richard M. Nixon makes a statement during an informal visit to UN Headquarters, during which he met with Secretary-General U Thant. UN Photo

02 February 1969 – Secretary-General U Thant paid an official visit to Ethiopia, and attended the 10th anniversary commemorations of the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) in the capital, Addis Ababa, where UNECA is still located. Shown here, the UN chief, accompanied by the Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie I, and other dignitaries, attend the opening of an UNECA exhibition on small-scale industries. UN Photo

28 April 1969 – During a visit to attend a meeting of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in the Italian capital of Rome, Secretary-General U Thant met with Pope Paul VI. UN Photo

13 August 1969 – A special ceremony was held at UN Headquarters for US astronauts Neil Armstrong, Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr. and Michael Collins of the Apollo 11 mission to the moon. Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant delivers a speech honouring the astronauts (standing left to right: Mr. Collins, Mr. Aldrin Jr., and Mr. Armstong). UN Photo

26 September 1969 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant greets the Prime Minister of Israel, Golda Meir, during an official visit to UN Headquarters. UN Photo

11 November 1969 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant meets the Prime Minister of Canada, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, during an official visit to UN Headquarters. UN Photo

26 January 1970 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant shakes hands with the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Harold Wilson, during an official visit to UN Headquarters. UN Photo

28 May 1970 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant greets President Suharto of Indonesia during an official visit to UN Headquarters. UN Photo

10 August 1970 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant receives a gift from the President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Joseph D. Mobutu – a portrait of himself – during an official visit to UN Headquarters. UN Photo

08 October 1970 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant meets with the new Permanent Representative of Austria to the United Nations, Ambassador Kurt Waldheim, during the latter’s presentation of his credentials to the UN chief. The Austrian diplomat was to succeed U Thant as Secretary-General in 1972. UN Photo

26 October 1970 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant meets the President of Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios III, during a visit to UN Headquarters. UN Photo

01 March 1971 – Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant meets the new Permanent Representative of the United States to the United Nations, Ambassador George H.W. Bush, during the presentation of his credentials. The US official went on to serve as his country’s 41st president between 1989-1993. In a speech to the General Asembly in 1990, amid concerns over tensions in the Persian Gulf, he said: "The founding of the United Nations embodied our deepest hopes for a peaceful world, and during the past year, we've come closer than ever before to realizing those hopes. We've seen a century sundered by barbed threats and barbed wire give way to a new era of peace and competition and freedom." UN Photo

For all his stoicism U Thant was certainly wounded by such a shameless onslaught, and from the summer of 1967 his health steadily declined. Ironically, in the following year, when his term of office ended and he announced that he wished to leave, he was relentlessly pressured to stay on as Secretary-General by the very governments who had made him a scapegoat over the Six Day War. Foolishly, he eventually gave in to this pressure.

U Thant’s final years at the UN were sad. For much of the time he was sick, and often out of the office. To his great distress, Ralph Bunche, who, at his insistence, had also stayed on at the UN, went into a steady physical decline and died in November 1971, two months before U Thant himself left the UN.

A few years after he left the UN, U Thant died of cancer of the jaw, perhaps the legacy of the exceedingly strong Burmese cheroots he loved to smoke. He has been largely forgotten, and when his name does come up, it is still usually in connection with “U Thant’s War,” as some journalists liked to call the Six-Day War that he alone tried to prevent. When the Cold War ended, and it became possible for Russians and Americans to discuss what had really happened in the most dangerous crisis in human history, the Cuban Missiles Crisis, U Thant’s role was revealed, although larger political egos on both sides still claim exclusive credit for avoiding catastrophe. As it became possible to discuss the war in Viet Nam objectively, his efforts to end that nightmare have also begun to be recognized. What has been more easily forgotten is the courage, decency, and generosity of a responsible, good, and modest man.