From extradition risks to broader implications: Human rights expert breaks down Assange case

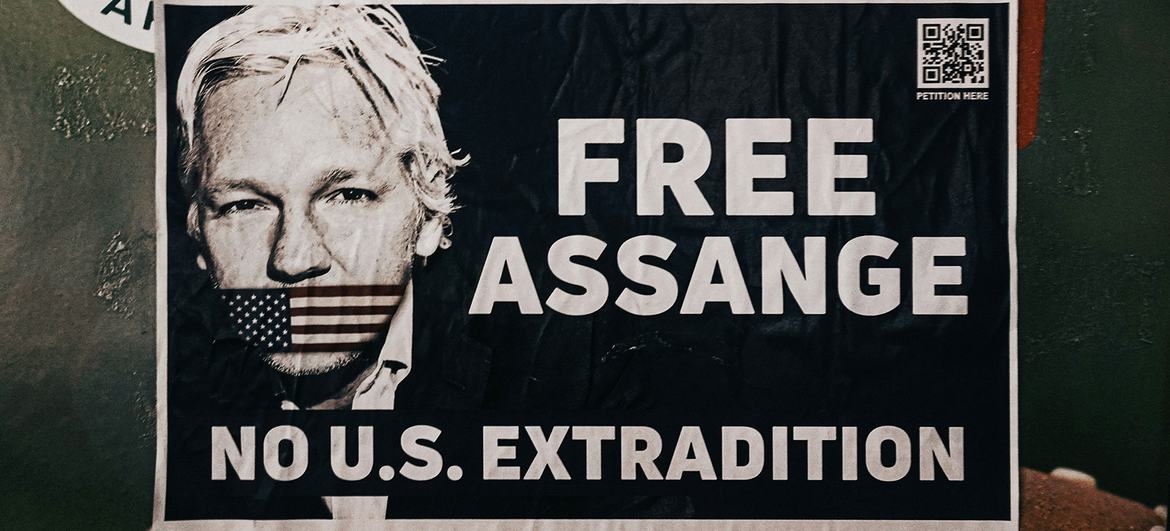

Ahead of Julian Assange’s upcoming court hearing in the UK, where extradition to the US is a possibility, a UN independent human rights expert has expressed concern about the potential for severe rights violations against the WikiLeaks founder. Alice Jill Edwards cautions that the repercussions of this case could significantly influence global journalism and freedom of speech.

Ms. Edwards, the Special Rapporteur on Torture, has appealed to UK authorities “to halt any possible extradition for fear that Mr. Assange health may be “irreparably damaged” by extradition.

In an interview with UN News’ Anton Uspensky, Ms. Edwards details her concerns for Mr. Assange’s mental and physical health and says, “the world is watching this case very, very closely”, including the outcome’s possible implications for free speech globally.

A final domestic appeal after a long-running legal battle on Mr. Assange’s extradition is scheduled to take place before the High Court in London on 20-21 February.

Mr. Assange faces 18 criminal counts in the US for his alleged role in unlawfully obtaining and disclosing classified documents related to national defence, including evidence exposing alleged war crimes.

He has been detained in the UK since 2019, where he is currently being held at Belmarsh prison.

Special Rapporteurs are human rights experts appointed by the UN Human Rights Council on specific thematic issues. They work on a voluntary basis and are independent of any government or organisation. They serve in their individual capacity, are not UN staff and do not draw a salary.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

UN News: Why are you worried by the possible extradition of Julian Assange from the United Kingdom to the United States? What are the key legal and human rights arguments against such a decision?

Alice J. Edwards: The case of Mr. Julian Assange has been a long running legal saga in the United Kingdom, spanning a number of years. My role as UN special rapporteur is to speak out whenever I take the view based on substantive information, for example, that someone may be sent to where they face a real risk to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment.

The United Kingdom is a party to the UN Convention Against Torture, as well as the European Convention on Human Rights. Both [instruments] have an equivalent article, Article 3, which prohibits states from sending people to where they may face this type of treatment. In the case of Mr. Assange, based on the materials that I’ve been provided and on what has also been documented by the court, there are three reasons why I am particularly concerned at this stage in respect of the United Kingdom being able to fulfil its obligations under Article three.

And the first is that Mr. Assange – and it’s well documented and also accepted by the court, and why his extradition has been suspended up to today – is that he suffers from a depressive disorder. Any extradition to the United States is very likely to exacerbate his medical underlying conditions – and there is a very real risk of suicide.

The second reason is that Mr. Assange is facing a remand in the United States while awaiting trial and during his trial. If convicted, of course, he would also then be punished by imprisonment. The United States has a long history of using isolation and solitary confinement, which is holding people in their own individual cells without daily interactions.

The Nelson Mandela Rules which govern [the standard minimum rules for treatment of prisoners] this indicate that 15 days of being in isolation or solitary confinement amounts to torture. So, there’s a high likelihood that any form of isolation and solitary confinement, especially prolonged solitary confinement, will have an irreparable impact on Mr. Assange’s psychological and even potentially physical health.

And the third reason why I believe that this extradition would likely fall afoul of the Article 3 protections is that Mr. Assange faces a penalty of 175 years. He has been charged with disclosing diplomatic and other cables which were of a confidential nature, including evidence of alleged war crimes. And he faces 175 years now. We can all do the math: Mr. Assange is 53 years old. This is over three times his current age. And of course, it amounts to 175 years, which is longer than anyone lies these days and is therefore two and a half times an ordinary life sentence.

In other countries, of course, life sentences are set by law. In Australia, for example, the penalty is up to 30 years – and as low as 10 – set statutorily. The European Court of Human Rights has accepted that grossly disproportionate penalties – which I consider 175 years for the charges against Mr. Assange would amount to – and excessive punishments are ill treatment under international law.

UN News: As someone who has been tracking the developments in Mr. Assange’s case, could you tell us if his current conditions are in keeping with the conventions – the way he is treated and kept in confinement now?

Alice J. Edwards: That I can’t actually respond to. My predecessor did visit Mr. Assange in the Belmarsh maximum security prison. I have not done so, and it has been a number of years since a visit by an official UN person was undertaken.

UN News: What is your message to the UK authorities, and have you had any reaction from them? Any comments regarding your appeals?

My appeal to the United Kingdom is for the courts – this is a process that is going through the courts. But ultimately, it’s up to the Secretary of State to determine whether the extradition will take place should the court permit it. My appeal is for some solution to take place in the case of Mr. Assange. This is the final domestic appeal for Mr. Assange.

This is the end of the line for his range of appeals. It’s very important that this case is considered very carefully because of the very dire consequences for Mr. Assange... his health and well-being. Those are my appeals to the British authorities.

UN News: Do you think the extradition of Mr. Assange might set a dangerous precedent for press freedom and journalism worldwide or for cases of whistleblowers and journalists?

Alice J. Edwards: I consider that states should be able to engage diplomatically and have confidential correspondence between themselves. Indeed, our international peace and security depend on that level of security. However, human rights require that we are also transparent when there are transgressions that occur, or war crimes as has been alleged in relation to some of the cables and information that were released.

Every law, whether it’s a treason law or national security law, should have whistleblower protection incorporated or a defence of whistleblowing. At this stage, that is not the case in the United States, as I understand it. The law that is being applied has not been updated to reflect human rights standards of the 21st century. And that is very problematic for others who are in a similar situation as Mr. Assange, who may wish to blow the whistle on information for activities that are being carried out by their governments or alleged to be carried out by their governments.

In fact, the whole international system works on the basis of our ability to speak our minds, to speak freely and to disclose and to call to account governments for potential violations. And then, of course, accountability should follow.

So, the world is watching this case very, very closely. I would like to see that the United States and the United Kingdom come to some resolution … that does not require Mr. Assange to be extradited to the United States given his current medical conditions.