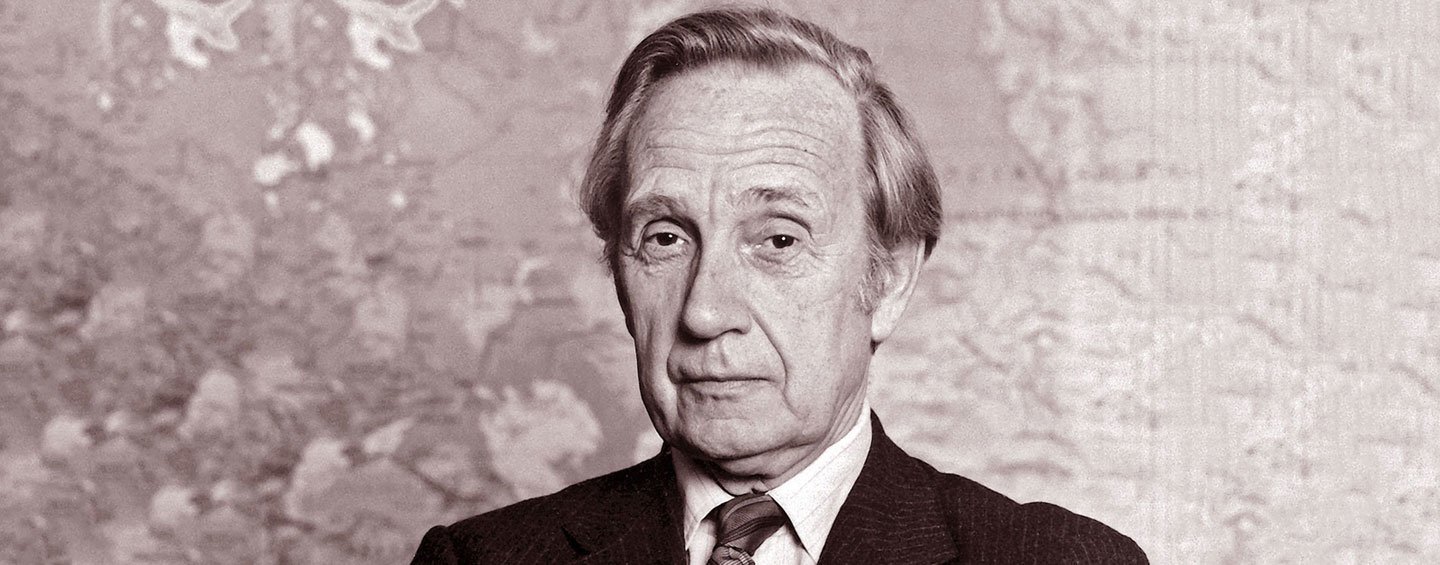

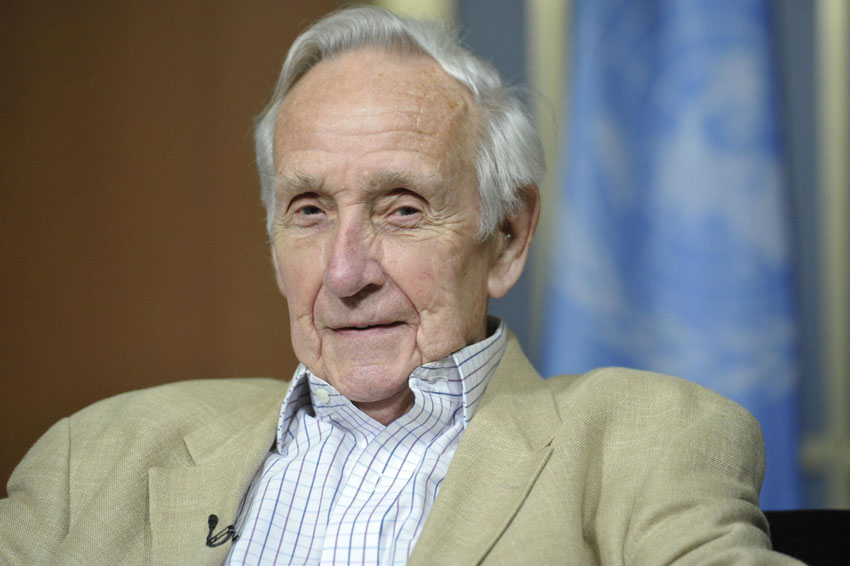

Interview with former UN official Brian Urquhart (Part 1)

Sir Brian Urquhart, who celebrates his 94th birthday in February, is a living chronicle of a large chunk of 20th-century history.

Throughout his four decades of service to the United Nations, starting as one of its very first staff members and ending as an Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs, he also helped shape history-making moments. He was present for the birth of the United Nations in 1945, and was witness to many of the Organization’s – and the world’s – seminal milestones.

All of these easily amount to a front-row seat on history. But Sir Brian’s links to history go even further. As a youth, his experiences include attending a lecture given by Indian independence leader Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi while in primary school and taking part in the coronation of King George VI.

I had a wonderful time working for the UN. It was quite difficult sometimes, but it was what I wanted to do... I loved the job, I believed in it. I still believe in it.

As a soldier in World War II, he was involved in the surrender of German scientists working in nuclear research; he was one of the first Allied troops to liberate the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp; and he even helped Danish author Karen Blixen, of 'Out of Africa' fame, out of a predicament at the end of the war. To top it off, his role in 'Operation Market Garden' – one of the most well-known military actions of the later stages of the war – was immortalized in an epic film.

As Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said in a tribute message on the occasion of Sir Brian’s 90th birthday four years ago, “You have had an enormous influence on every Secretary-General. Even today, staffers everywhere seek to live up to your example. And you remain one of our wisest and staunchest advocates.”

Here, in the first installment of a two-part feature, UN News spotlights the experiences and views of Sir Brian leading up to the creation of the United Nations.

Sir Brian Urquhart was born in his grandfather’s house in 1919, in Bridport, Dorset, on the southern coast of England, the younger of two sons. Due to a lack of money, between the ages of six and eight, he was enrolled at a school in Bristol at which his mother taught: the Badminton School for Girls. In his autobiography, Sir Brian wrote that international affairs formed a large part of the school’s teaching, describing it as “an excellent school with some very un-English characteristics. Of these one of the most important was a passionate anti-xenophobia.” The school was founded by the sister of Sir Brian’s mother and her partner – Aunt Lucy and Ms. Beatrice M. Bake, two ladies who supported the work of the United Nations’ forerunner, the League of Nations.

UN News: The thrust of your early education seems to have foreshadowed the international path your life has taken. What influence do you think your Aunt Lucy and Ms. Bake had on you?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Absolutely enormous. They were formidable ladies, as was my mother actually. They had a civil belief that the League of Nations ought to work. They didn’t think it would work, because governments weren’t capable of making it work, but they thought something like that had to work. They had a huge influence. Then, of course, we got into World War II, and it collapsed. But I had always wanted to work at the League of Nations. By the time I got there, anywhere near it, of course we had the war so I was in the army instead.

Following an eventual transfer to a preparatory school for boys, at the age of 11 and at the insistence of his headmaster who knew of the financial situation of Sir Brian’s family, he sat for what was then known as the King’s Scholarship exam for Westminster School in London.

He described passing the exam as a “turning point because it gave me affordable access to an ancient and civilized school for the next six years.”

UN News: About your experience in the British schooling system in the 1920s and 1930s, you wrote that “if you were very lucky you received that intellectual stimulus, the essential shot-in-the-arm, that changes the way you think and look at life” and that you fell into that category. Just how important was education for your development?

Sir Brian Urquhart: My father was an extremely unsuccessful painter, actually a rather good painter but he didn’t make any money. So I had to get scholarships, which in those days you got on merit, and I managed to do that.

I went to Westminster which gave a traditional, classical education – that is to say that you learned Greek, Latin and philosophy. My mother thought that was a mistake, so I did foreign languages. I got to the top of that at the age of 15 and I had two years to go [to finish school].

I was lucky I transferred to the history part of the school, which was run by a school-master straight out of Evelyn Waugh: John Edward Bowle. He was an absolutely brilliant, extremely eccentric person who was able, in some extraordinary way; to get one to write; to get one to think about contemporary problems; to read history in a rather personal way and to see how it all came together. I’m very grateful to this remarkable teacher.

Sir Brian’s six years at Westminster School were formative. His schoolmaster, John Edward Bowle, had his students read and discuss contemporary books, and would bring in the authors to address the 16-year-old students. Some of those who spent afternoons engaging the students in discussion on their books included Bertrand Russell, Arnold Toynbee and H.G. Wells. After finishing high school, Sir Brian attended Oxford University as a Hinchcliffe Scholar at Christ Church College. His time at the university coincided with various events in Europe and the world in general, from the Spanish Civil War to the Italian conquest of Abyssinia, which preceded World War II.

UN Secretary-General, Trygve Lie, confers with the Executive Secretary of the Preparatory Commission of the United Nations, Gladwyn Jebb. Sir Brian Urquhart worked for both men. (1 January 1946) UN Photo/Marcel Bolomey

UN Secretary-General, Trygve Lie, confers with the Executive Secretary of the Preparatory Commission of the United Nations, Gladwyn Jebb. Sir Brian Urquhart worked for both men. (1 January 1946) UN Photo/Marcel Bolomey

UN News: You wrote that Westminster School left you with the ingrained idea on the concept of service. How is that?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Well, that was true, you know, almost across the whole British public school system, because the system, as such, was designed to staff a very large empire run by a small, off-shore island. I mean the idea was that unless you were some sort of kind of a genius, like a musician or a painter or a poet or something, you should concentrate on the idea of serving. And it wasn’t a priggish idea – it seems to be not a bad idea really – and I think we were very much brought up to think that unless we displayed some fantastic genius for something, we would be lucky to be in public service, or indeed earlier on, to go into the church – the Church after all is a state religion in England, unbelievably – or to go into the army, to come to that. These were the main sources of public service. I wanted to be a civilian. And, you know, I think it wasn’t a bad idea – although bad luck on all those people we were going to rule over in the colonies – so you trained a whole group of people who would do that, and, incidentally, who would go to some distant part of the world and stay there their whole working life.

UN News: What kind of a student were you?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Well, I had to be very good because otherwise I, first of all, wouldn’t have gotten a scholarship to a public school and then I wouldn’t have gotten a scholarship to Oxford, in which case I would have gone and worked in a bank. So I was quite a good student!