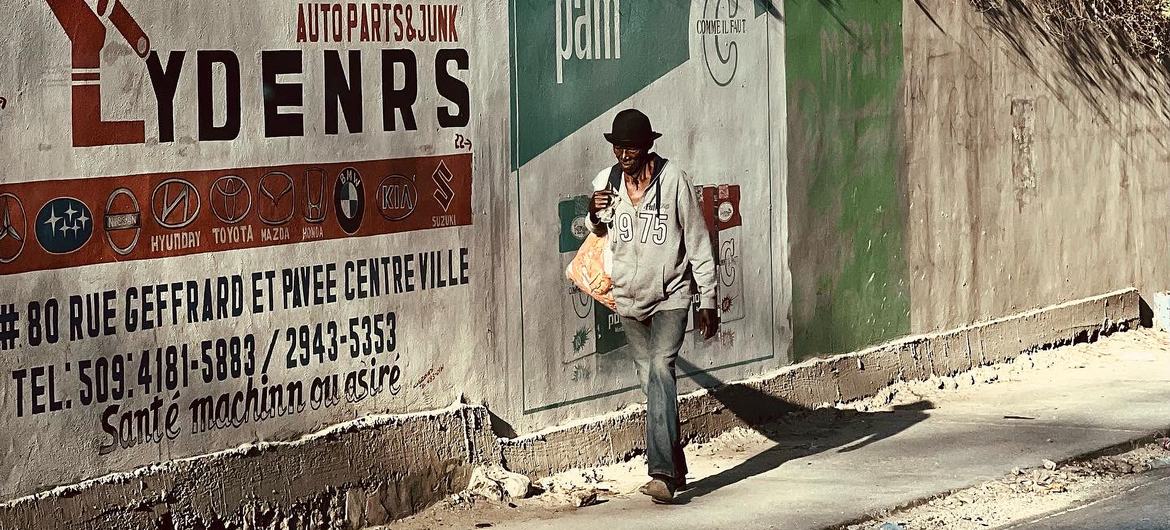

First Person: Visions of hell, in Haiti

Samuel (not his real name) grew up near the Haitian Capital of Port-au-Prince, and has seen his childhood home descend into lawlessness and gang violence. Now a staff member with the UN Development Programme (UNDP) in the country, he faces the daily risk of kidnapping, or worse.

"I spent much of my childhood in the south of the capital, in Cité Plus, from the age of 10, until I got married 16 years later. Back then, it was a peaceful neighbourhood, but it has been transformed into a lawless, hellish zone.

We didn’t grow up wealthy, but we always had enough to eat, and my parents made enough to send me and my three siblings to private schools. I went on to study philosophy at the University of Haiti, as well as law and economics and eventually as a multimedia journalist. I joined UNDP in 2014.

Constant insecurity

Through my work with UNDP on the ground, we get to meet principled, resilient people who believe in a better future with a strong community spirit, who work hard, in the absence of basic public services.

And, at our offices, I work with extraordinary colleagues, who maintain their professionalism and work effectively, despite the many crises that have an effect on their personal and work lives.

However, we all work under a persistent sense of insecurity, and the fear that people will find out where we work.

Many people believe that all UN staff members and people who work for international organisations are rich, and this gives rise to jealousy and even hatred, amongst those who don’t have the same opportunities as us, in a country with a very high rate of unemployment.

With the alarming rise in the number of kidnappings we have seen recently, this sense of insecurity is increasing.

A life-threatening commute

I knew that, as a staff member for an international organization in Port-au-Prince, it would be recommended that I live in certain neighboUrhoods, and would have to be careful who i shared my personal and professional information with.

Over the last year, as the security situation has deteriorated, I have also had to be careful which roads I take to get to work. This is the case for me, and other colleagues who live in areas affected by rising insecurity such as downtown Port-au-Prince, Carrefour, Mariani, Merger, Gressier, or Léogâne.

My wife and I are obliged to stay with family in Port-au-Prince during the week, even though we have built a family home elsewhere. Our two children are at school close to where we built our home, and we can only hope to see them on the weekend, if we are able to make the journey.

Otherwise, we can only communicate by telephone, as if we were living in another country.

Commuting is too dangerous. The authorities have lost control of main transportation routes to the south and east of the city, through areas such as Martissant and Croix des Bouquets, and gangsters are pillaging the population, raping women and shooting at passengers on buses or in cars.

Horrors on the road

Travelling by road means accepting that you will be driving past human bodies, left on the roadside to be eaten by dogs. I doubt that those killed in Martissant even figure in the official death statistics.

Things really were different before. During my childhood, Cité Plus was like many other neighbourhoods of Port-au-Prince. There were many poor families, single mothers, and children whose parents couldn’t afford to feed them or send them to school, but there was less crime.

Today in Haiti, ideas such as free choice, free movement, and security are becoming more and more removed from reality.

‘I feel as if I’m in a country that is dying’

The future of Haiti is very uncertain. It is as if we live in a failed State. I don’t feel that we have the leaders in a position of authority to restore order.

It’s a situation of total terror. I feel as if I’m in a country that is dying.

Whatever happens, I will fight to survive, no matter what. But to survive, you need to stay alive, and I’m worried that the insecurity is getting closer and closer to me.

Many of my acquaintances have become victims of violence and kidnappings, either directly or indirectly. I fear that my wife and children are targets for criminals.

Given the current situation, many people have left the country, and many more are planning to leave. Even the intellectual elite, those with a decent quality of life, are emigrating.

I want to stay in a Haiti whose institutions work for its citizens, without any discrimination, where inequality is reduced, and all citizens have access to basic services.

I don’t think that Haiti is necessarily doomed. We can find our way out of this mess, as long as there is a collective awakening, and a critical mass decides to get us back on track. But this will require a lot of sacrifices, and a willingness to act in the collective interest.