Coronavirus a challenge, and opportunity, to fix remittances system than funnels billions home from abroad

Often the equivalent of several hundred dollars a month, remittances – the money that migrant workers send home to their families – have been adding up in a big way to contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that will especially benefit families in developing countries, and keep tens of millions out of poverty.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic – and, ironically, a chance to improve a unique segment of the global financial system that accounts for more than five per cent of gross domestic product for at least 60 low- and medium-income countries – more than the total of foreign direct investment or official development assistance handed out by governments.

Vulnerabilities exposed

“Regardless of whether nor not the (post-coronavirus) recovery will be faster than expected, the global pandemic has exposed the vulnerabilities of the global remittances system,” said Gilbert F. Houngbo, President of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), a specialized agency of the UN in Rome.

“That is why now is the time to fix these vulnerabilities no matter what the economic scenario will be”, he told UN News in the run-up to the International Day of Family Remittances on 16 June.

Last year, remittances to low- and medium-income countries hit a record $554 billion, according to the World Bank, with 200 million migrant workers in 40 rich countries sending home funds to support 800 million relatives in more than 125 developing nations.

Half of those receiving families live in rural areas where remittances count the most, Mr. Houngbo said.

$110 billion drop off

But with the onset of the novel coronavirus pandemic, the World Bank projects that cross-border remittances will fall by 20 per cent, or $110 billion, to $445 billion, potentially pulling tens of millions below the poverty line while undermining progress towards fulfilling the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

With no V-shaped recovery likely in 2021, savings will be depleted, and local conditions will worsen, as remittances are not expected to return to pre-pandemic levels for some time, Mr. Houngbo explained.

“While the reduction in remittances will not fall evenly on all families, nor across all continents, societal impacts will be substantial and sustained”, he told UN News via e-mail.

Remittance Community Task Force

In response, IFAD has for two months been leading the Remittance Community Task Force, comprising 35 organizations, that has issued a series of concrete recommendations that address the impact of COVID-19 on the lives of one billion people directly involved in remittances.

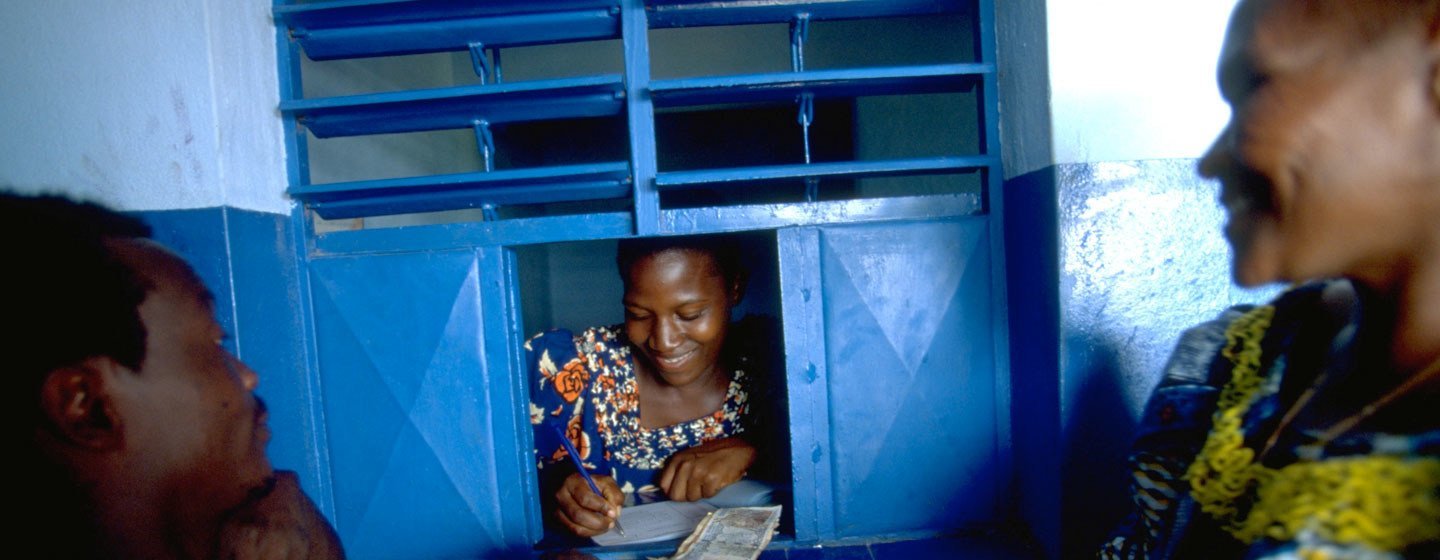

It wants remittance service providers to be designated essential businesses in times of crisis, and for ensured access to remittances services, especially in poor rural areas, with incentives to use digital remittance products.

It also recommends linking remittances to a full range of financial services and productions, as well as fast-tracking implementation of the UN’s call for faster, safer and cheaper remittance transfers.

In the same vein, Switzerland and the United Kingdom – joined by several other Member States, the World Bank, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and other UN agencies and industry groups – issued a global “call to action” on 22 May to ensure that migrant workers and diaspora communities can keep sending back money in ways that can also improve the remittance system.

It urges policymakers to declare the provision of remittances as an essential public service and to support the development of more efficient digital remittance channels. To regulators, the “call to action” requests guidance for “know-your-customer” requirements - critical for scaling up digital financial services, particularly for undocumented persons with no access to a bank account.

It goes on to encourage remittance service providers to explore ways to ease the burden on their migrant customers by lowering transaction fees, which now average 6.8 per cent worldwide, more than half the target set in the Sustainable Development Goals, according to the World Bank’s most recent Migration and Development Brief.

‘A lifeline in the developing world’

“Remittances are a lifeline in the developing world – especially now,” said Secretary-General António Guterres on 19 March. “Countries have already committed to reduce remittance fees to 3 percent…The crisis requires us to go further, getting as close to zero as possible.”

For its part, the IFAD says it is partnering with financial technology firms, mobile operators, commercial banks and postal networks, to integrate digital solutions to improve remittance transfers to rural areas.

Coronavirus Portal & News Updates

Readers can find information and guidance on the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) from the UN, World Health Organization and UN agencies here. For daily news updates from UN News, click here.In addition to its Financial Facilities for Remittances initiative, it is strengthening the ability of rural families to weather tough times through financial literacy and planning programmes, among other capacity-building efforts.

Mr. Houngbo, a former Prime Minister of Togo who has led IFAD since 2017, said that for the past 15 years, the focus of international attention on remittances has been on the “sending side”, particularly high transaction costs.

“We need to emphasize, however, that the development impact of remittances is really on the receiving end – where, at this time, families are struggling with the sudden disruption of their economic lifelines,” he said.