Despite progress in childbirth safety, one woman or baby dies every 11 seconds

Childbirth survival rates are now a “staggering success” compared with the year 2000, but one pregnant woman - or her child - still dies every 11 seconds from largely preventable causes, UN health experts said on Thursday.

In a joint appeal for all nations to do more to provide better medical care for all, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) outlined several ways to help protect the 2.8 million pregnant women and newborns who die every year.

A skilled pair of hands to help mothers and newborns around the time of birth, along with clean water, adequate nutrition, basic medicines and vaccines, can make the difference between life and death. #EveryChildALIVE https://t.co/H3cKi5QgFz

unicefchief

Their recommendations tackle immediate and underlying problems, such as ensuring that midwives have water to wash their hands and helping teenage girls to stay in school longer, where there is less chance of them getting pregnant.

In addition, communities should have access to cheap medicines, such as oral rehydration salts used to treat diarrhoea, and “ten cent vaccines” to keep tuberculosis at bay, the UN agencies insisted.

Citing 2018 data showing that newborns – babies in their first month - accounted for around half of the 5.3 million deaths among under-fives, WHO and UNICEF also highlighted the need for other structural changes.

These include ensuring that pregnant mothers eat a sufficiently nutritious diet to stave off illnesses linked to malnutrition.

Sub-Saharan babies, 10 times more likely to die

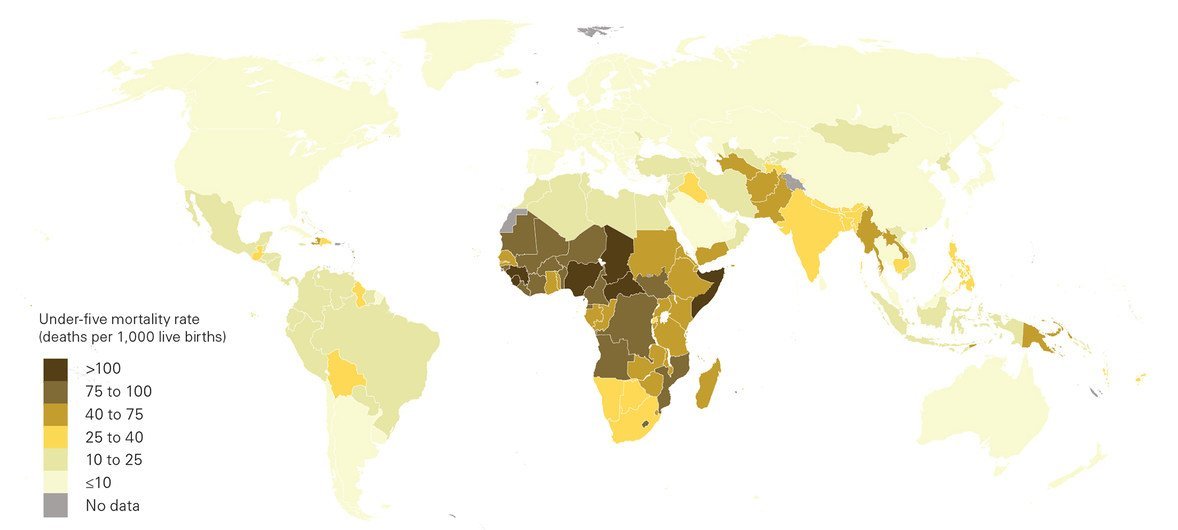

All of these things “can make the difference between life and death”, said UNICEF Executive Director Henrietta Fore, in a statement accompanying new data showing that in sub-Saharan Africa, women in childbirth are nearly 50 times more likely to die, than in richer regions, and their babies are 10 times more likely to perish in their first month.

According to 2018 figures, one in 13 children in sub-Saharan Africa also died before their fifth birthday, which is 15 times more than in Europe, where the rate is one in 196.

Beyond sub-Saharan Africa, the joint WHO/UNICEF report also expressed concern about high mother and baby mortality rates linked to poverty in Southern Asia.

Taken together, both regions account for around eight in 10 of all maternal and child deaths, highlighting vast inequalities in healthcare worldwide.

Going to Sweden ‘can reduce mother’s chances of dying by 100’

“If I look to my own native country, Sweden (a woman) who travels from the highest mortality regions to the world to Sweden, she reduces her overall mortality rate by 100”, UNICEF’s Chief of Health, Dr Stefan Peterson, told journalists in Geneva.

Under global healthcare targets agreed by the international community in 2015 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2030 Agenda, Goal 3.2 calls for fewer than 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030.

“The world will fall short of this target by more than one million lives if the current pace of progress continues”, the agencies warned.

Another SDG target (3.2) urges countries to reduce deaths of babies in their first month of life, to at least 12 per 1,000 live births, and to bring down mortality among under-fives, to at least 25 per 1,000 live births.

In 2018, 121 countries had already achieved this under-five mortality rate, according to WHO, while among the remaining 74 States, 53 will need to accelerate progress to reach the SDG target on child survival by 2030.

$200 billion needed to achieve healthcare targets

Some $200 billion a year is needed to achieve all the primary health goals that are required for quality universal health coverage for all, according to Dr Peter Salama, Executive Director in charge of Universal Healthcare targets at WHO.

Welcoming the many positive changes in tackling child and maternal mortality globally since 2000, Dr Salama insisted that many countries were in a position to achieve much more, without having to find new funding.

“The biggest difference in terms of when we discuss financing between the MDG (Millennium Development Goals) era (2000-2015) and the SDG era, is the real acknowledgement that the money is there for many countries, they just have to spend it on the right things,” he said.

“So we’re not turning to the donor community and saying, ‘Give us $200 billion.’ We’re turning to middle-income and higher-income and even some lower-income countries that are stable and saying, ‘Actually, if you choose the right things, you could meet these goals within your current budgets.’”

‘Staggering success’ in reducing deaths

Since 2000, Dr. Salama insisted, the overall story of maternal and child mortality had been “a staggering success that we don’t often see in global and health development”.

He pointed to a 50 per cent reduction in deaths in children under 15 years old – from 14.2 million in 2000 to 6.2 million deaths in 2018 - and a 35 per cent reduction in maternal deaths over the same period.