The Last Swiss Holocaust Survivors: Keeping the memory alive

After the Second World War, 90 per cent of the Holocaust survivors were between 16 and 45 years old. Today, the youngest survivors, who were born in the last phase of the war, are over age 70.

Some endured concentration and extermination camps, while others escaped by fleeing or hiding.

For the majority, returning to their homeland was not an option, so they emigrated to Israel or the United States.

It wasn’t until the investigations of the Bergier Commission on dormant assets in the late 1990s that the public became aware of the Holocaust survivors living in Switzerland – most of whom travelled to the country only after the war.

The number of survivors is steadily decreasing.

Switzerland – which now presides over the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance that unites governments and experts to strengthen and promote Holocaust education and remembrance globally – sponsored the exhibition on survivors at United Nations Headquarters in New York.

Portraits of Holocaust Survivors tells the stories of individuals who are among the last survivors and how they carried on with their lives in Switzerland after the war. The exhibition is one of several events surrounding the annual commemoration of the International Day of Commemoration in memory of the victims of the Holocaust (27 January).

The memories of the survivors

Anita Winter, President of the Gamaraal Foundation, which helps alleviate financial distress of Holocaust survivors, is the child of survivors. Seeing the difficulty with which the survivors spoke of their experiences, she felt deeply thankful to them for sharing their stories.

According to Ms. Winter, many told her personally that they felt it was their duty to speak on behalf of the six million who can no longer speak for themselves. For her, their resilience is amazing.

Born in 1932, Nina Weil lived in what is today the Czech Republic. In 1942 she was deported to Theresienstadt and later arrived at Auschwitz with her mother, who died at age 38 of exhaustion. Ms. Weil survived a “selection” by camp doctor Josef Mengele as well as a labour camp.

Ms. Weil shared her distress: “They tattooed me: 71978. I cried a lot. Not because of the pain, no, because of the number. Because I had lost the name, I was just a number. My mother said, ‘Do not cry, nothing has happened. When we get home, you visit the dance school and get a big bracelet so no one sees the number.’ I never went to dance school and never got the bracelet.”

Ms. Winter recalled an unsettling story that Ms. Weil shared with her about taking a trip to the hospital for bloodwork, where a young technician mistook the number she had tattooed on her arm at the concentration camp for her phone number.

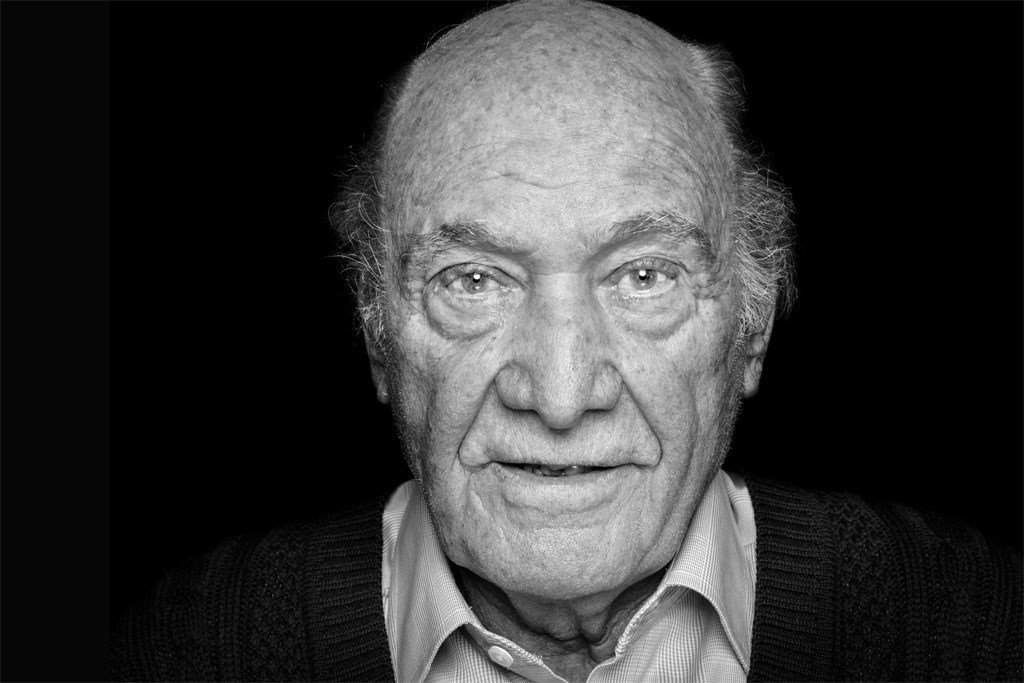

Eduard Kornfeld survived both Auschwitz and Dachau camps. He grew up in Bratislava, Slovakia, and was arrested in 1944 while hiding with his brother in Hungary.

After the war, in which he lost his entire family, he arrived in Davos weighing only 27 kilos, or 60 pounds, weak and sick from exhaustion. There Swiss doctors saved his life.

Mr. Kornfeld said, "We were deported in a cattle car, the journey took three days. When the train suddenly stopped, I heard someone shouting outside in German, 'Get out!' I looked out of the carriage and saw SS officers beating people they thought were moving too slowly. A mother wasn't moving quick enough because she was trying to take care of her child, so the SS officers took her infant and threw him in the same truck they put the old and sick. Those people were sent to be gassed immediately."

Ms. Winter remembered Mr. Kornfeld telling her about his emaciated state upon arrived in Switzerland, saying that when he looked in the mirror he did not even recognize himself.

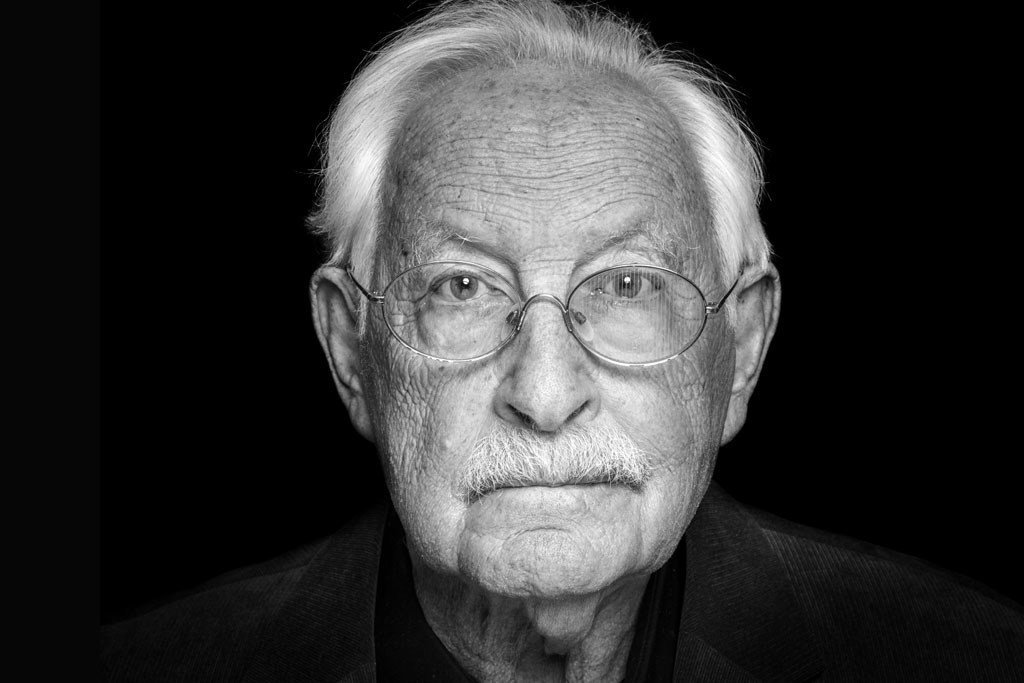

Klaus Appel was born in 1925 in Berlin. After his father, Paul, and his older brother, Willi-Wolf, were arrested and sent to Auschwitz, he and his sister came to England in one of the last Kindertransport humanitarian programmes. After the war, Klaus married a Swiss woman, moved to western Switzerland and worked as a watchmaker. He died in April 2017, 10 days before this exhibit was launched in Switzerland.

Mr. Appel explained, "We were at home when the doorbell rang. They had come to arrest my father. 'Are you Mr. Appel?' they asked him. 'Then come with us.' My father just calmly turned to me and said, 'You are going to school.' That was the last thing he ever said to me. I never saw him again."

Reflecting upon Mr. Appel who passed away in 2017, Ms. Winter reminisced how he worked hard to share his experiences with young people, visiting schools and universities.

President and Founder of the Gamaraal Foundation, Anita Winter, shares short stories about three of the survivors Nina Weil, Eduard Kornfeld and Klaus Appel.