FEATURE: From misplaced emblem in London to iconic hall – the UN General Assembly across 70 years

Before there was a United Nations Secretary-General, a Security Council or an iconic Headquarters in New York, there was the General Assembly, the most representative body ever of world nations, meeting for the first time in a London hall facing Westminster Abbey, the 1,000-year-old coronation site of Britain’s kings and queens.

It was here on 10 January 1946 that representatives of the then 51 Member States came together in Westminster Central Hall, a Methodist church and conference centre, before a semi-circular dais beneath the now famous UN emblem of a world map as seen from above the North Pole, flanked by olive wreaths – affixed back to front on the wall.

What a difference seven decades make.

Now, Heads of State and Government from 193 nations gather in the majestic, newly renovated General Assembly Hall at UN Headquarters in New York at the beginning of the new session in September each year against a gold-leafed background, beneath that equally gleaming emblem – this time the right way round.

This Hall has echoed with the soaring rhetoric of monarchs, presidents, popes and prime ministers. It has also resounded to more doubtfully memorable interventions.

A wide view of the General Assembly Hall during the sixty-ninth session in September 2014. UN Photo/Amanda Voisard

On 12 October 1961, the echo was the sound of Soviet Prime Minister Nikita Khrushchev pounding his shoe on his desk when the Philippines delegate accused his country of swallowing up Eastern Europe.

On 20 September 2006, then Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, taking the podium a day after United States President George W. Bush, announced that it still smelt of sulphur because “the devil came here yesterday.” He made the sign of the cross, clasped his hands as if in prayer, and looked briefly upwards as though to invoke God, eliciting giggles from some delegations.

In 1977 and 1978, Sir Eric Gairy, Prime Minister of the Caribbean island nation of Grenada had flying saucers, officially called unidentified flying objects (UFOs), put on the Assembly’s agenda.

On 23 September 2009, Libya’s then leader Muammar Ghaddafi extended his allotted 15-minute speech time to one hour and 40 minutes of diatribe, during which he tore up the UN Charter on this self-same podium.

And for 22 years after the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had taken control of Beijing and its then 700 million or more people, the UN still recognised the Taiwan-based Republic of China, with less than a fiftieth of that population, as the representative of the Chinese people and holder of UN Security Council permanent membership – until the General Assembly on 25 October 1971 passed Resolution 2758 giving recognition to the PRC.

Leading diplomats and statesmen to the United Nations Organization’s General Assembly attended a banquet as guests of King George VI in London on 9 January 1946, on the eve of the convening of the Assembly’s first session. UN Photo

But on that distant London winter afternoon in 1946, all these events were far into the future, and the UN was still officially referred to as UNO – for United Nations Organization.

At 4 p.m., Colombian Foreign Minister Eduardo Zuleta Ángel, chairman of the Preparatory Commission of the United Nations, declared the meeting open.

“Determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind, and imbued with an abiding faith in freedom and justice, we have come to this British capital, which bears upon it the deep impress of heroic majesty, to constitute the General Assembly of the United Nations to make a genuine and sincere beginning with the application of the (founding) San Francisco Charter,” he declared.

“It is an arduous and difficult duty but one we can and must discharge without delay, for the whole world now waits upon our decisions and rightly – yet with understandable anxiety – looking to us to show ourselves capable of mastering our problems.”

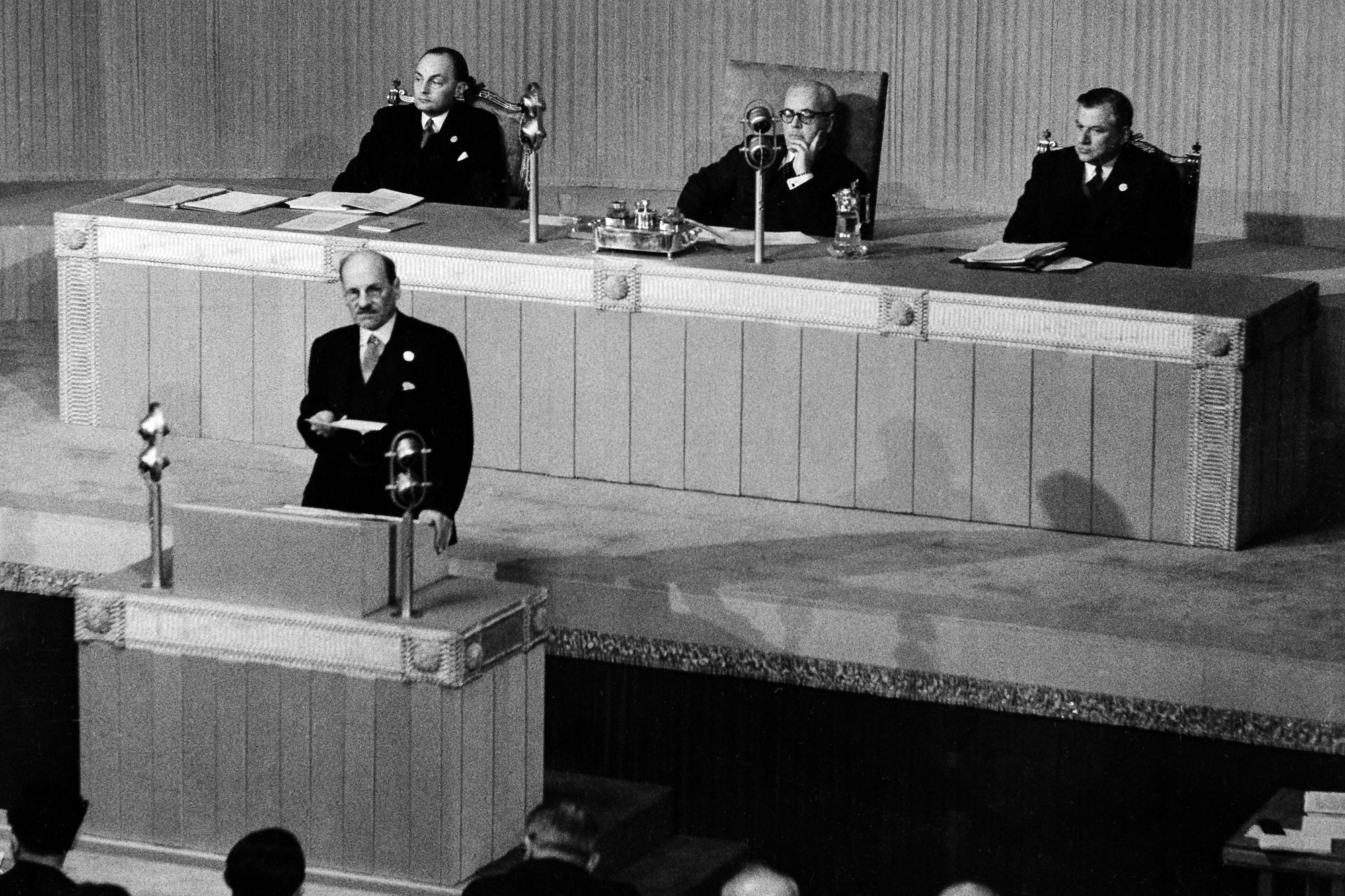

A view of the podium as Clement Atlee, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, addresses the first session of the UN General Assembly when it opened on 10 January 1946 at Central Hall in London. UN Photo/Marcel Bolomey

In his address, then British Prime Minister Clement Atlee stressed that “The United Nations Charter does not deal with governments and States, but with the simple, elemental needs of human beings, whatever be their race, their colour or their creed...

“Should there be a third world war, the long upward progress toward civilization may be halted for generations. Bearing in mind the great sacrifices that have been made, to prove ourselves no less courageous… no less patient, no less self-sacrificing, we must, we will succeed.”

The Assembly then went on to elect its first president – Belgium’s Paul-Henri Spaak, who obtained 28 votes against 23 for Norwegian Foreign Minister Trygve Lie, who was backed by the Soviet bloc.

Paul-Henri Spaak (Belgium) addressing the General Assembly during its opening session on 10 January 1946, shortly after his election as its first President. To his right is Gladwyn Jebb, Executive Secretary of the United Nations. UN Photo/Marcel Bolomey

A week later, on 17 January, the UN Security Council held its first meeting at nearby Church House, headquarters of the Church of England next to Westminster Abbey.

Less than a week after that, on 23 January, the UN Economic and Social Council opened its first session at Church House.

The following day, on 24 January, the General Assembly adopted its first resolution – the establishment of a commission to deal with the problem raised by the discovery of atomic energy.

And a week after that, on 1 February, still in London, Mr. Lie, losing candidate for General Assembly president, was elected the UN’s first Secretary-General.

The General Assembly is officially categorized the UN’s main deliberative, policymaking and representative organ, with decisions on important issues such as peace and security, new members, and budgetary matters requiring a two-thirds majority instead of a simple majority.

But it does not have the final say, since its decisions are not legally binding, as are resolutions by the 15-member Security Council, with which all Member States are obligated to comply.

This has led to much criticism from many developing States who gained membership long after 10 January 1946, when they won independence from their colonial rulers.

They complain that the arrangement is undemocratic, especially as the five permanent members and original Second World War allies – China, France, Russia, United Kingdom and the US – have veto powers.

A view of Central Hall Westminster on 24 October 2015, when over 300 sites around the world were lit up in UN blue – the official colour of the UN – as part of a global campaign to commemorate UN Day and the Organization’s 70th anniversary. Credit: Maria Schuett

Every year during the Assembly’s annual General Debate, scores of leaders take to the podium to call for Security Council reform, expanding its membership with new permanent and non-permanent members, with the former also having veto powers, or eliminating the veto altogether in the interests of democracy, equality and true representation.

Current Assembly President Mogens Lykketoft has already taken steps to increase the 193-member body’s role in the selection of a new Secretary-General this year at the end of Ban Ki-moon’s second term.

According to the UN Charter, the Secretary-General is appointed by the General Assembly following the Council’s recommendation.

Now, candidates will be given the opportunity to hold informal talks with Assembly members. “The wish is that the membership, for the first time in UN history, is included totally in the discussion of the next Secretary-General," Mr. Lykketoft said in December, calling it “a watershed in the way that we are doing things.”

“Until [today], the selection process of the Secretary-General has been very secretive and involving mostly – or only – the permanent five members of the Security Council,” he stressed.

Of course, he continued, the permanent Council members “still have a very strong position in selecting proposals for the General Assembly, but I think if, out of this new process we are now embarking on, comes an imminent candidate supported by a majority of the membership, it will actually give the general membership an increased, de facto power in selecting the Secretary-General.”

The presentation of candidates will give Member States the opportunity to ask questions about their positions on UN priorities, such as the Sustainable Development Agenda, and peace and security, he noted.