"We’ve learnt many lessons from this outbreak and from the response" – Dr. David Nabarro, Special Envoy on Ebola

In August 2014, amid a rapidly growing outbreak of Ebola, Dr. David Nabarro was tasked with providing strategic guidance for an enhanced international response, and galvanizing essential support for affected communities and countries. As the Secretary-General’s Special Envoy on Ebola, Dr. Nabarro played a key role in responding to the outbreak, which mainly affected Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, and claimed more than 11,300 lives to date.

Dr. Nabarro, a national of the United Kingdom with over three decades of experience in public health, nutrition and development work, spoke with the UN News Centre about the achievements of 2015, the priorities ahead for next year, as well as the lessons learned from the outbreak and the international response that followed. He also explains how the experience gave him an opportunity to see the human spirit at its best, such as he had never seen it before.

UN News Centre: Can you give us an overview of the current situation regarding the Ebola outbreak?

It’s really important that we continue to have a high degree of vigilance right through 2016 until we can be sure that transmission is completely ended.

David Nabarro: The Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the largest that we’ve ever seen, was intense in September and October last year and then started to decline significantly in early 2015. Throughout this year, it has continued to decline with a slightly bumpy road at the end with occasional flare-ups. But in Sierra Leone, transmission of Ebola has finished and we’re in a period of enhanced surveillance. In Guinea, we expect transmission to finish before the end of this year. Liberia, which had reported an end to Ebola some months ago, had a flare-up recently in Monrovia and is dealing with that situation now, and we anticipate that in Liberia transmission will end early next year.

But I want to stress that this has proved to be a very difficult outbreak to end and therefore, it’s really important that we continue to have a high degree of vigilance right through 2016 until we can be sure that transmission is completely ended.

UN News Centre: What has been achieved in 2015? Are we past the worst of it, or is there concern that the infection could resurface?

David Nabarro: In 2015, we have seen a gradual decrease in the number of people with Ebola in West Africa. At the beginning of the year, the number of cases reported each week was of the order of 150. That’s 150 people infected, of whom a significant proportion will not survive. Throughout the year, the number has declined, bit by bit, and often we had periods when we wondered how we were going to see an end to the outbreak. But it has steadily declined with the number of cases reaching zero most quickly in Liberia, followed by Sierra Leone and then Guinea. But it’s not been easy. And that’s because the virus survives despite the fact that people are cured of the disease. And it stays in body fluids, particularly in semen but also in other parts of the body, including the eye of certain people. And that means that it is possible for people to continue to transmit the virus even when they have been cured and that leads to the possibility of flare-ups. That’s why the end of the outbreak has been so difficult but it’s proved possible to reach this point through the steady and continuous involvement of thousands of people involved in the response.

UN News Centre: What do you see as the main priorities for the Ebola response as we enter 2016?

David Nabarro: As we enter 2016, we must be aware that the virus is still present in the bodies of many of those who have survived the disease. We reckon there are about 15,000 people who were sick and were cured. And of these, a proportion – we don’t know how many – are still carrying the virus in their bodies. And it’s particularly the case for men, who continue to have the virus in their seminal fluid, and that means that they may unwittingly pass the virus onto others. So our first priority is to help ensure that those who’ve survived the disease can access good quality care and support so that they themselves are kept healthy and also to reduce the risk that they’ll pass the virus to other people.

Our second priority is to be sure that if there is a small flare-up, the countries and indeed the rest of the world are ready. And we’ve already seen on a number of occasions during this year, 2015, that this rapid response capacity is there.

Our third priority, and perhaps I think we’d say the most important of all, is to make sure that services, particularly health care, for the millions of people in these countries return to normal, and are in fact made better, as quickly as possible. And that recovery and rebuilding is the primary focus for so many of us at this time.

UN News Centre: Given the closure of the Office of the Special Envoy at the end of 2015, will the UN system still be involved next year?

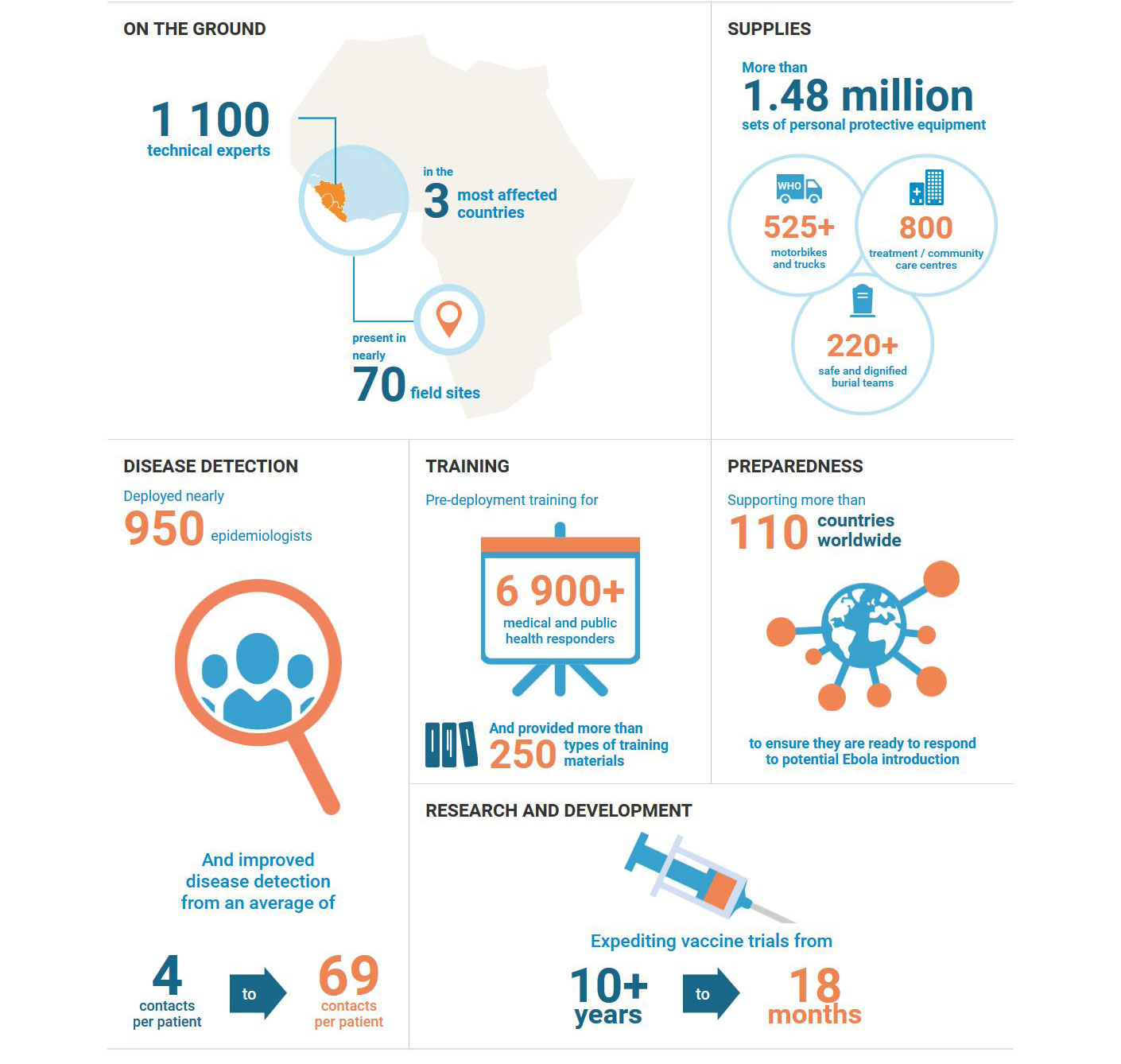

David Nabarro: The United Nations has had a very strong involvement in this Ebola outbreak, really since it started because we’ve had teams in the countries who have worked with the national offices in order to do their best to get on top of it. It has been difficult because the outbreak did catch us by surprise and was much more ferocious than anything we’ve ever seen before in terms of the number of people affected and the speed of spread. During August last year, the number of people with Ebola was doubling every three weeks. The United Nations, under the leadership of our Secretary-General and with the full involvement of the World Health Organization and all other entities in the UN system, came in with the strongest possible response that built up, so that by the end of 2014 we had of the order of 3,500 staff working in support of the countries. Gradually, our numbers of staff have reduced as the outbreak has subsided. But even now, there are several thousand UN staff in the countries and in the vicinity who are working in support of the response, and they’re going to stay there. We will continue to back the countries with personnel, both for responding to the outbreak and to the threats of recurrence and for the recovery.

My office, the Office of the Special Envoy, ends its time on December 31st 2015. But I will personally stay continuously engaged in the issue, working with the World Health Organization, working with governments, working with partners to try to keep a close eye on what is happening and to ensure that the whole UN system continues to fully engaged with the affected countries.

UN News Centre: You mentioned there are some 15,000 survivors. What is life like for them, their families and communities? And what kind of support do they need?

David Nabarro: The people who have experienced Ebola are really extraordinary. They’ve been close to death and they have come back. They’ve clung onto life and they have recovered. But it is a terrible disease. It makes people extremely ill when they get it because they lose fluid, they bleed, they have terrible fevers, awful headaches and their joints, in fact the whole of their bodies, ache. It hurts. But they, when they pull through, are truly the heroes.

The outbreak did catch us by surprise and was much more ferocious than anything we’ve ever seen before in terms of the number of people affected and the speed of spread

First of all, they get continued headaches and sometimes also mental discomfort leading to severe depression. They get eye problems that can continue even after the Ebola has been treated and the patient is cured. The eyesight deterioration may even lead to blindness, certainly some visual impairment in at least 10 per cent of affected people. Then they get joint discomfort and they hurt even when sitting, but certainly when walking and they are unable to move around which means that if they’re working in fields, they can’t deliver the agricultural production that they would really like to. And perhaps most seriously, they experience terrible stigma from the rest of society, and it’s not helped by the fact that there’s an increasing recognition that some of them may still carrying the virus in their bodies. So these hero survivors are also people who suffer in health terms and in socio-economic terms. So they need help.

What we in the United Nations system is doing is trying to make sure that every person who survives Ebola has access to the care that they need from anybody who can provide that care, whether it’s from government or a non-governmental organization. And it’s trying to ensure this universal access to survivor care that is our priority right now and we’re working on it really very intensively, trying to identify resources so that the care can be available and then try to make sure that every survivor has a mentor who is with them to help them get the care that they need.

UN News Centre: Ebola wreaked havoc not only on the lives of people but on the hard-won development gains in these countries. What will it take to get these countries on a solid path to recovery and development?

David Nabarro: I worked in Liberia shortly after the end of the war in the early 2002-2003 period, trying to see what could be done to help the country recover and get back onto the path to development. And I saw just how terribly badly it had been affected by war and how its systems were really damaged and battered, and the people’s confidence in government and what government could offer was very much shaken. But during the period after the Liberian war, there has been an extraordinary recovery and that recovery was looking really good, and then along came Ebola, setting the government and people back almost worse than the point that they were at immediately after the war. The same is the case in Sierra Leone, another war-torn country that had been painfully recovering with people regaining confidence in what government had to offer, and then again badly knocked back by Ebola. Guinea is a different country – it hadn’t had these terrible wars but still it had been affected by many difficulties… it’s an extremely poor country. And Guinea too has been badly affected by Ebola.

And it’s not just the effect of the disease on health services, which are after all the worst affected by an outbreak like Ebola, it’s also the impact on other aspects of life in the country – on transportation, on trade, particularly business, on the agriculture sector, and on the industrial sector – all affected by the outbreak, leading to a cutback in economic growth that was quite significant. And that was coupled with the effect of commodity prices falling on the world markets, which also impacted on the economic opportunities for the countries. And then added to that was another injustice, which was the quite dramatic cutback in links between these countries and the rest of the world – maritime links because ships were not docking in the ports, and air links because for various reasons a number of airlines decided to stop flying to this region and many of them have still stopped flying and have not restarted their flights.

So taken together, the direct effects on services, health, education and social support, the effects on commerce, on agriculture, and on transport in country, which affected internal economies very badly, and then the effects on international links, on sea and on air in particular, have had an overall negative impact on the economies. And it will take years… I suspect five years… for recovery to take place and that’s why the recovery conference that took place in New York on July 10th was so important in setting the stage for long-term support by the international community for these countries and for the great people who’ve done all the work and for their leaders who have led them so strongly through the outbreak.

UN News Centre: What were the main lessons learned from this outbreak and the response that followed?

David Nabarro: We’ve learnt many lessons from this outbreak and from the response. First of all, we’ve learnt that, as with all diseases, it’s really important that communities are fully engaged in both the identification of the disease and the response right from the start. After all, you get the disease through contact with somebody else who’s got it. And it’s got to be close contact. And so, if it’s human behaviour patterns that lead to risk of disease, it’s communities themselves that are going to be the first to find ways to reduce physical contact and reduce the risk of spread. And so communities that got involved and that owned the disease were the first to be able to shift from being in a situation where the disease instance was high to being in a situation where it dropped and they were able to prevent themselves from being sick. Community engagement is the key and it’s the centre.

The second thing that I learnt and that many of us now feel is really important is that this kind of outbreak can’t be handled by outsiders just simply on their own. It’s got to start from within the countries. It’s national leadership, from presidents, from ministers and from leaders in government, in civil society, in faith communities, coming to the centre and showing the way. Often parliamentarians play a key role and certainly in each of the countries, it was the local representatives, the traditional chiefs and others who were at the centre. And so it’s the countries themselves that have played the leadership role. And I give particular credit to health workers from Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea who have borne the risk and have done the heart of the work.

Third lesson that I’ve learnt is that when the outside world gets involved, and it did get involved in an extraordinary way in this situation, we need early support, we need coordinated support and we need that support to be put at the disposal of the countries.

My fourth and last lesson that I’d like to share is that we’ve also learnt that when you’ve got multiple groups involved in a response, it is necessary for there to be one identified location from which the whole operation is directed – what we sometimes refer to as command and control. Because if you don’t have that central direction, a strong and unequivocal central direction, it’s very difficult to get everybody working together. And that command and control is necessary at the local level, at the community level I mean, as well as at the national level and regionally. So taken together, community engagement and ownership, countries being at the centre of the response operation, the importance of a coordinated international support, and then command and control are all things I see as important. And I would add, try always to make certain that this support is available early on. If you get in early and act early, you can prevent the situation from deteriorating and that’s what in future I hope we will be able to do much better.

UN News Centre: As a life-long public health and international development official, what has this experience as Special Envoy on Ebola been like for you on a personal level?

David Nabarro: When I look at the outbreak and my involvement in the outbreak since August last year, and I link that other work that I have done in public health over the last three decades, I am consistently humbled by the power of individuals, communities and coordinated groups of people to transform the lives of others. In this outbreak, we have seen numerous examples of individual and collective courage, bravery, commitment, compassion, and continuous selfless giving. It’s hard to explain it without perhaps sounding a little bit idealistic. But I want to share it with you because it’s so important to me.

I can identify hundreds of people who have worked tirelessly on this outbreak since the very beginning and who have just said ‘I’m not going to stop.’ They’ve been offered periods of vacation and rest and recuperation, but they’ve stayed on the job, working 24 hours a day, seven days a week. I’ve seen people who have gone way beyond what their normal responsibilities are to try to bring relief and help to people who’ve been suffering. And I have seen continuous efforts by everybody to just work together and to get on well. There have been remarkably few tussles between organizations about who’s in charge, remarkably few episodes of name-calling and anger. Instead, everybody’s just pulled together to try to transform the situation so that the suffering is reduced.

Of course outsiders have kind of assessed what we’ve been doing and have made properly critical judgments and the lesson-learning effort must go on. But all I can say is this has been the most remarkable opportunity to see human generosity, human commitment and the human spirit in its best force that I have ever seen in my life. And I hope that we can remember this forever because what it shows is that if we pull together to respond to a desperately difficult situation of suffering for thousands of people, we can be transformative and we can make life better for all. And we can do it without fussing about who we work for or what our motives are. We can do it because we believe in the good of humanity. That has been my real lesson and that’s one that I will never forget.