Reverse exodus: refugees flee Yemen for strife-riven Horn of Africa, UN reports

“We have many refugees who recently arrived to the camp, and we can see from their faces and

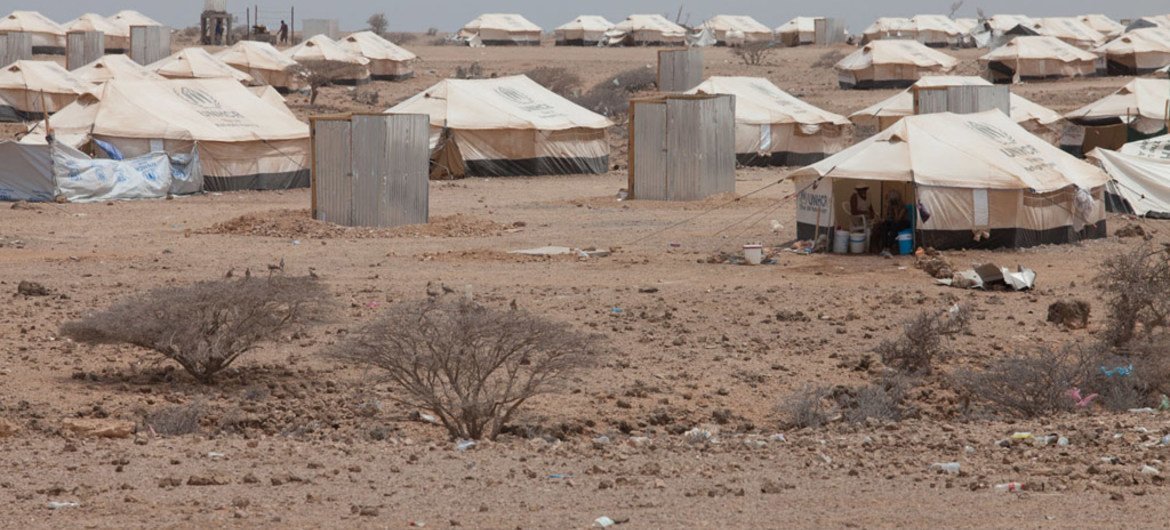

whenever we talk to them that they are traumatized,” says Abdul Rahman Mnawar, community services officer at Markazi camp where the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and its partners are providing aid in this small desert country in the Horn of Africa.

“They have been through a lot during their flight,” he added, stressing that one of the most urgent issues is providing counselling and emotional support, especially to those who witnessed violence and killings first hand.

As fighting intensifies in Yemen, over 120,000 refugees and migrants have fled since April, with more than 15,000 seeking safety in Djibouti, according to UNHCR.

Though the numbers pale in comparison to the refugees who have fled Africa to Yemen – last month UNHCR reported that there were some 265,000 there, over 250,000 of them Somalis, beyond the countless thousands who fled in previous years and moved on – they are still significant in Djibouti, whose total population is about 820,000.

One of those who fled here is Yemeni fisherman Seif Zeid Abdulah, who was riding home on his motorbike when an airstrike pounded his native Bab El Mandab region. A sudden, concussive blast sent the 27-year-old flying. His left leg shattered by shrapnel, he found he was bleeding heavily from a wound that would require months of rehabilitation and treatment.

“I'd lived in fear that something like this could happen to a close family member, a friend or a neighbour. Then all of a sudden my leg is torn and I am crippled,” he said.

Fearing that medical facilities might become targets – as they already have in the conflict – Zeid Abdullah and other war-wounded civilians are increasingly reluctant to seek public health care within Yemen. Moreover, soaring costs of private clinics are forcing them to seek alternatives.

A slight figure, whose shattered leg is held together by pins, he decided to save his scarce funds and cross to Djibouti in late October, believing he would have a better chance of survival as a refugee.

“In Yemen, I came across many men, women and children whose health is deteriorating due to unhealed wounds,” he said. “I am glad that some have already crossed. I hope the remaining will manage to cross as well,” he added.

Supporting himself on crutches, his wounds exposed to the air, Zeid Abdullah registered as a refugee in the port town of Obock. He is looking forward to safety, protection and medical assistance in Markazi from UNHCR and its partners.

Imad Ali, 28, fled in late October. Crossing the 30-kilometre strait with four other Yemeni men on a seven-metre-long boat, the fisherman left his parents and other siblings back in the port city of Aden, where they first sought refuge.

“I stayed in my native region of Bab El Mandab because someone had to work and provide for the big family despite the high risks,” he said. “But I realised soon after this war is worsening, and I don't have the means to bring everybody to Djibouti.”

He opted to cross to Djibouti to join his fiancée and her family who had settled beforehand as refugees in Markazi camp. “At least, my in-laws can become my second family” said Ali.

Since the end of September, more than 2,000 Yemenis have fled to Djibouti, bringing the number in Markazi camp to around 2,800. As violence at home rages on, seeking safety on the western shores of the Gulf of Aden is increasingly becoming the only resort for thousands of Yemenis.

“We are at about full capacity in Markazi camp,” said Mr. Mnawar. “We already need to plan the extension of the camp to welcome additional refugees.”

Not that the violence in Yemen has stopped Somalis from still seeing it as a refuge from their own violence-torn country. UNHCR reported last month that 70,000 refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants crossed over to the country.

The sea route is extremely dangerous, and 88 deaths have been recorded so far this year. The crews of the people-smuggling boats also frequently brutalize the passengers.

According to UNHCR, the exodus to Yemen has shifted eastwards from the Gulf of Aden to the Arabian Sea coast where people believe the situation is calmer, resulting in over 10,000 new arrivals in September, a 50 per cent increase on August, and over 10,000 in October.