Persistent vulnerability threatens human development, warns flagship UN report

Reducing vulnerability and strengthening resilience are critical to securing human development progress, the United Nations says in a flagship report released today that examines the risks posed by natural or human-induced disasters and crises and offers ways to tackle them.

The 2014 Human Development Report, launched in Tokyo by the UN Development Programme (UNDP), says that 1.2 billion people live on $1.25 a day or less. At the same time, the UNDP Multidimensional Poverty Index reveals that almost 1.5 billion people in 91 developing countries are living in poverty with overlapping deprivations in health, education and living standards.

Although poverty is declining overall, almost 800 million people are at risk of falling back into poverty if setbacks occur, according to the report, entitled “Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience.”

“Setbacks are not inevitable. While every society is vulnerable to risk, some suffer far less harm and recover more quickly than others when adversity strikes,” noted UNDP Administrator Helen Clark.

“By addressing vulnerabilities, all people may share in development progress, and human development will become increasingly equitable and sustainable.”

This year’s report explores structural vulnerabilities – those that have persisted and compounded over time as a result of discrimination and institutional failings, hurting groups such as the poor, women, migrants, people with disabilities, indigenous groups and older people.

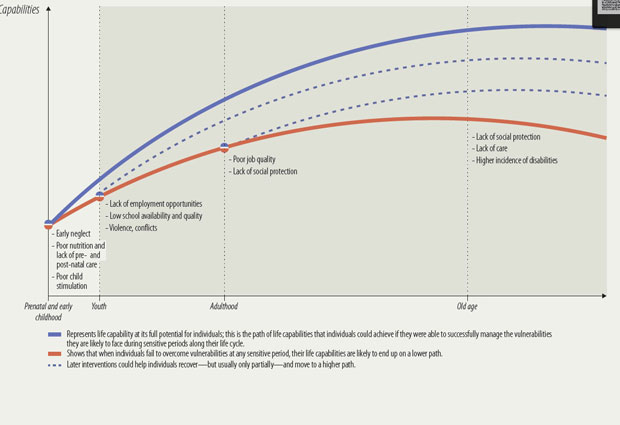

It also introduces the idea of life cycle vulnerabilities – the sensitive points in life where shocks can have greater impact. These include the first 1,000 days of life, and the transitions from school to work, and from work to retirement.

Speaking to the UN News Centre, Khalid Malik, Director of the Human Development Report Office, highlighted how the 2014 report differs from last year’s, which was more upbeat.

“The 2013 report was about how so many more people are doing better, particularly over the last decade. This year’s report is also trying to look at those who have not done so well. And also look at how the world itself is getting a little bit more fractious, a little less predictable,” he said.

“There is a growing sense of unease as if somehow people are not in control of their own destinies. It’s both at the country level and it’s also on the global level. And this report tries to dig into those issues of vulnerability and then try to understand what policies, what measures are needed to make people and societies more resilient.”

Among other recommendations, the report calls for universal access to basic social services, especially health and education; stronger social protection, including unemployment insurance and pensions; and a commitment to full employment, recognizing that the value of employment extends far beyond the income it generates.

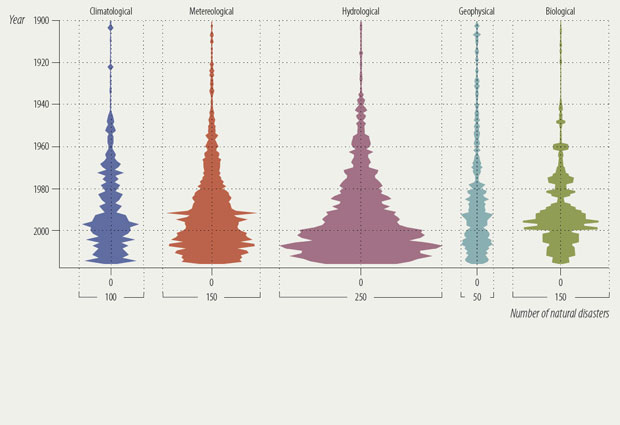

It recognizes that no matter how effective policies are in reducing inherent vulnerabilities, crises will continue to occur with potentially destructive consequences. Building capacities for disaster preparedness and recovery, which enable communities to better weather – and recover from – shocks, is vital.

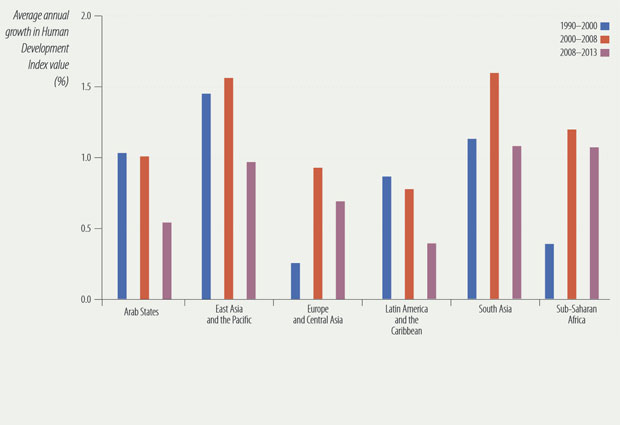

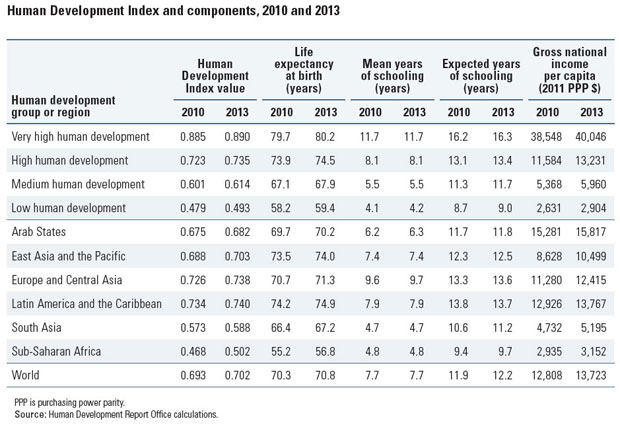

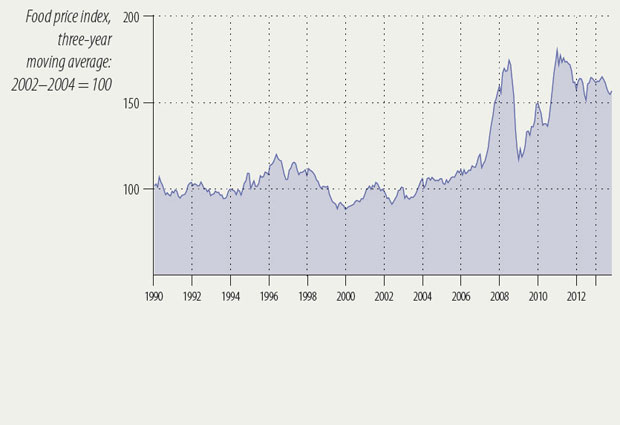

This year’s report also points to a slowdown in human development growth across all regions, as measured by the Human Development Index (HDI), pointing to threats such as financial crises, fluctuations in food prices, natural disasters and violent conflict that impede progress.

Zimbabwe experienced the biggest improvement due to a significant increase in life expectancy – 1.8 years from 2012 to 2013, almost quadruple the average global increase.

Meanwhile, the rankings remain unchanged at both ends of the Index. Norway, Australia, Switzerland, the Netherlands and the United States remain in the lead for another year, while Sierra Leone, Chad, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Niger continue to round out the list.

The steepest declines in HDI values this year occurred in Central African Republic, Libya and Syria, where ongoing conflict contributed to a drop in incomes.

A new index featured this year is the Gender Development Index (GDI), which for the first time measures the gender gap in human development achievements for 148 countries. It reveals that in 16 countries (Argentina, Barbados, Belarus, Estonia, Finland, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Mongolia, Poland, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, Ukraine and Uruguay), female HDI values are equal or higher than those for males.

For some of these countries, this may be attributed to higher female educational achievement; for others, to a significantly longer female life expectancy – over five years longer than that of males.

Afghanistan, where the human development index for females is only 60 per cent of that for males, is the most unequal country.

Questions on the 2014 Human Development Report?

Join Guardian's live Q&A with UN Development Chief Helen Clark (@HelenClarkUNDP) on Twitter this Friday, 25 July at 10.30AM NY time/15.30 London time and ask your questions now using #askUNDP or by commenting on this Guardian article.