Violence against women: Prevention, protection and empowerment in Haiti

It is a lesser known reality of the earthquake that devastated Haiti on 12 January 2010 and left more than 200,000 dead. The merciless disintegration of the Haitian State created a situation of utter chaos for the country's most vulnerable.

In less than 55 seconds of tremors, 1.5 million people were suddenly stranded on rubble-strewn streets filled with the detritus of 80,000 collapsed buildings. Almost two years after the disaster, more than 650,000 people still live in makeshift camps, often in terrible conditions.

Even if the election of a new President, Michel Martelly, in May last year gave Haitians hope for the future, the new Government faces a highly unstable situation. Many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and UN agencies are preparing to shutter the emergency operations they set up in the immediate aftermath of the quake. The transition from emergency assistance to long-term development projects poses a growing challenge as hundreds of thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) still rely on aid to survive.

Among the displaced, women are particularly vulnerable as they face a surge in sexual assaults and domestic violence. In addition, precarious living conditions in the IDP camps as well as the overall weakening of local authorities provide criminals with opportunities to offend with impunity.

Despite the difficulties, women are slowly beginning to talk, says Celia Romulus, a project manager for UN Women, the agency fighting violence against women.

"We are confronted with dramatic situations in which young women are raped in broad daylight in their tents or even young children are being raped," Ms. Romulus says.

Sexual assaults are particularly difficult to identify, prevent and punish. As a result, the UN has strengthened its patrols in the camps, fielding more than 8,800 blue helmets, 1,244 members of the UN police force (UNPOL) and 2,337 police officers from formed police units (FPUs).

Strengthening security in the camps

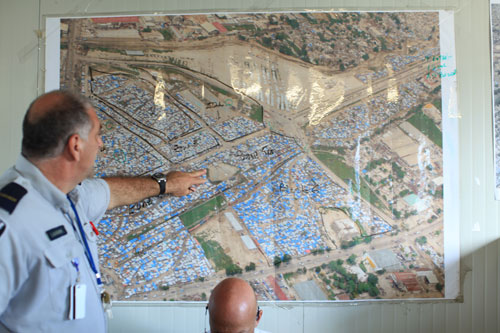

With more than 50,000 inhabitants, Jean Marie Vincent is the biggest IDP camp in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince, occupying several hectares of property near the city centre and close to Cité Soleil, one of the poorest and less secure areas of the city.

Raymond Lamarre, the UNPOL police spokesperson in Haiti, bluntly describes the difficulties faced by law enforcement: "The gangsters of Cité Soleil commit crimes and then hide in the IDP camp where it is more difficult for us and for the Haitian National Police (HNP) Force to track them down."

To dissuade these criminals, UN police concentrate their efforts along the camp's perimeter and at its entrances.

United Nations police (UNPOL) spokesperson in Haiti Raymond Lamarre visiting the Jean Marie Vincent camp, the biggest camp for internally displaced persons in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

"Intensifying patrols along the perimeter helps to reduce opportunities for committing crimes and it strengthens security for the IDPs," says Mr. Lamarre, noting that the new measures have led to a significant reduction in reports of sexual assaults.

"We have found out that the latrines are particularly dangerous for women at night. That's why we have decided to install lighting near these places where sexual predators happened to be lurking."

Despite the precautions along the camp's perimeter, violence inside the camp is still widespread, with UN officers coming under threat as well.

"For the first time, UN police have been targeted," notes Claude Mercier, the police officer in charge of an investigation into the recent shooting of UN personnel.

"Yesterday, shots were fired in the camp and we immediately dispatched a UNPOL team towards the location. One of the police officers was severely wounded and the culprit managed to escape. The body of a civilian was found not far from that place," he says.

With two police stations overseeing a population of 50,000 people, UNPOL officers admit it will take time to completely secure the camp. The upcoming departure of a large number of humanitarian organizations and the lack of resources available to the national police make the situation ever more fragile. For Mr. Lamarre, one of the solutions would be to forge relations of trust with camp residents.

"We are not perfect. We need to interact more with the population, forge ties, and create a situation of symbiosis between communities. We are here to build trust. I dare to think that we generate hope and change for the population," he says.

Break the law of silence, restore trust

Interview with Nalidjata Soumahoro, UN Policewoman in Haiti, Gender Unit.

In addition to the horrors of the crimes themselves, the criminals responsible for sexual assaults also have a feeling of impunity within the camps. These predators are often neighbours or associates of their victims and provoke fear of retribution if the victims report the crime. To break this wall of silence, the UN police have established a gender unit with 20 police officers, 15 of whom are women, dedicated to the prevention and the fight against sexual violence in the camps.

"We forge ties of trust with the population and that allows for female victims to come and see us when an incident of sexual aggression occurs," explains Nedea Valentin, the gender unit's deputy chief, who also points out that victims of sexual violence are more comfortable confiding in female officers.

As soon as an incident is reported, the female officers immediately engage in the standard operating procedure. First, the assault must be verified by a doctor within 72 hours the crucial timeframe within which sex crimes can be medically identified and treated at one of the local hospitals or special clinics set up by the NGO Doctors without Borders. Then, if the perpetrators are found and arrested, the officers bring the case all the way to the courts where they help victims plead their cases to the judge. At the same time, victims are provided with counselling and psychological support.

To eradicate the growing scourge of sexual violence, the gender unit dispatches teams of four to different camps throughout Port-au-Prince, conducting awareness seminars with the city's women. During the daily meetings, the officers discuss the ongoing fight against sexual and domestic violence but also the economic empowerment of women, the overall fight against poverty and family planning. One of the assumptions accepted by the team is that domestic and sexual violence are the collateral effects of the more entrenched economic and social violence suffered by women.

During one of the awareness sessions with the women of the Primature camp founded on the grounds of what used to be the Prime Minister's residence the conversation quickly turns to the soaring prices of basic food items, such as oil, rice and beans.

"Everything has become more expensive after the goudou goudou," says a young mother, referring to the local onomatopoeic name for the earthquake.

Undaunted, the gender unit's Nalidjata Soumahoro explains the advantages of the tontine a cooperative system based on the pooling of common savings.

"Each week around 15 women or more meet, each one of them bringing some money with her," says Ms. Soumahoro to the group. "And each week one of the women takes home all the money as capital to start a small business, whether it be selling mangoes, oranges, etc. The following week, another woman takes the pooled money in order to start another small business. This way, all the women receive the money they need to create a livelihood!"

For Fredrik Bjerkeborn, the Deputy UN Police Commissioner in Haiti, UNPOL's approach to dealing with gender issues contributes "positively to changing mentalities in the communities." Nevertheless, he notes that the road to gender equality in the IDP camps will be a long one because it is a long and profound societal process.

One of the most important measures implemented during the recent years of UN operations in Haiti was to increase the female presence among the peacekeepers. The Bangladeshi contingent of the UN police force now includes 108 women and is led by a woman Commissioner Sahely Ferdous.

Beyond the security aspects of the mission, the female presence in the UN police force proves to the locals that women can assume positions of power, and further illustrates that gender equality is possible. Moreover, the female presence in both the UN police force and within MINUSTAH is growing with a current total of 489 women serving in their ranks.

"It is important to train the Haitian National Police to make it able to tackle gender related problems," explains Mr. Bjerkeborn. "We provide specific training for the prevention of sexual violence. We explain the situation of women in the camps and we prepare them to answer questions that women in danger could ask and we teach them how to implement proper procedures to act immediately in case of a reported sexual assault."

He further points out that UNPOL aims to create special safe rooms where sex crime victims can express themselves freely, safely and anonymously.

Empowerment of women

Interview with Superintendent Sahely Ferdous, UN Police in Haiti.

Protecting women only makes sense if they are ultimately empowered by being able to identify and seize opportunities. For this reason, UN Women, the Organization's youngest agency, has promoted several initiatives to reclaim areas of IDP camps where women have been regular targets of assault.

"We try to eliminate their worst fears: violence in the public space," says Célia Romulus. "The idea is to turn women into their own security experts in their own environment."

To do that, the agency's local partners help organize safety patrols in the camp's neighbourhoods, walking the same routes as the women use to go to school, the market or to the various water pumps positioned around the camp. Along the way, they mark out areas where improved lighting or a police presence would help guarantee better safety.

This form of citizen's awareness has already yielded encouraging results as the women have become increasingly likely to report any instances of sexual violence.

"When our mobile teams arrest a suspect, and the wall of silence is broken, we show that sexual violence is unacceptable and that gives meaning to our work," states Sheila Laplanche, a communications specialist at UN Women's office in Haiti.

"We support the State in its efforts to establish a law on violence against women, and we also encourage female participation in political life as well as the creation of microcredit projects specifically for victims of violence," concludes Ms. Laplanche.

Célia Romulus stresses that UN Women's emphasis on listening has permitted women to be heard more easily in the aftermath of the earthquake.

"Very often, before speaking of the actual sexual violence, the victims first speak of the trauma of the earthquake. Then later, when trust is established they begin speaking about the aggression and the violence they have endured," she says, underlining that by focusing on listening to the victimized women, some have already begun to heal and rebuild their lives.

This gender-focused initiative completes the massive aid operation launched by the UN's humanitarian agencies in the immediate aftermath of the quake.

"Just by simply being there, in the middle of the rubble, and available to hear their stories," Ms. Romulus says, her voice choked with emotion, "the victims have thanked us for helping them get their dignity back."