Flow of Somalis fleeing famine starts to ebb – UN

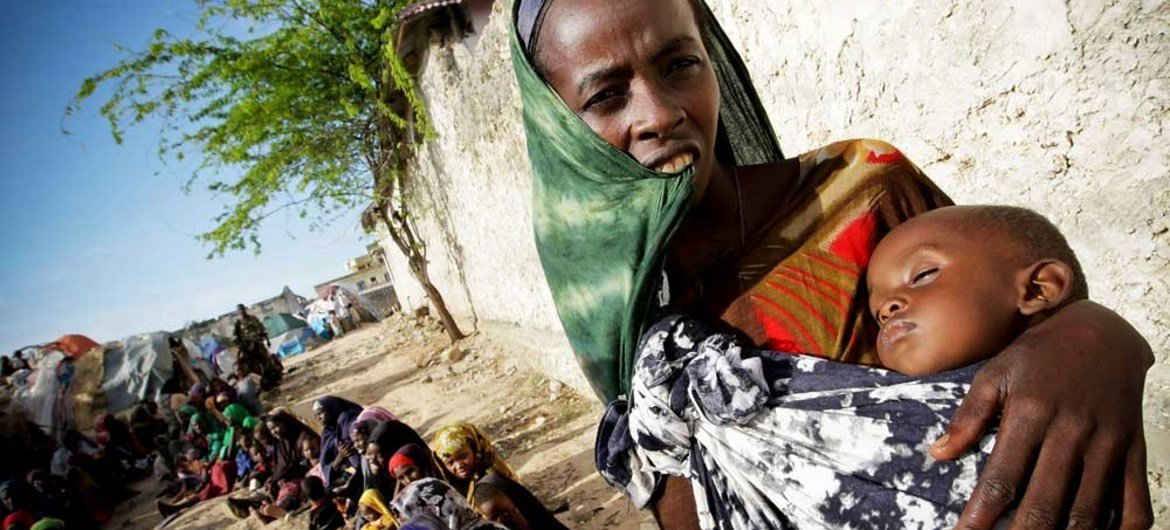

There was a significant drop in the number of people arriving in Mogadishu, the capital, which peaked in July, when nearly 28,000 fled to the city in search of aid after fleeing famine, drought and conflict in the countryside of the Horn of Africa nation, where tens of thousands of people have already died and some 3.2 million others are thought to be on the brink of starvation.

“Since the beginning of this month, just over 5,000 displacements into the city have been recorded,” UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) spokesperson Adrian Edwards told a news briefing in Geneva. “The average daily arrival rate in the city dropped from more than 1,000 per day last month to an estimated 200 in August.”

Due to insecurity, almost no movements were recorded in districts of Mogadishu held by Al-Shabaab until earlier this month. African Union (AU) peacekeepers have also imposed restrictions on civilian movement to areas previously controlled by Al Shabaab, which is reportedly restricting movements, particularly of men, in areas still under its control in the south, Mr. Edwards said.

He noted that donations from the Somali diaspora and mobilization by local and host communities to assist affected populations during the Islamic fasting month of Ramadan may have enabled people to remain where they are, while international and local organizations have been better placed to deliver aid to the famine-stricken in several areas, particularly along the borders with Kenya and Ethiopia.

Arrivals of Somali refugees in neighbouring Kenya’s Dadaab region also slowed this month to 1,000 to 1,200 a day from 1,500. But the overall health state of the latest arrivals, particularly the children, is worse. Dadaab now houses almost 500,000 people, mostly Somalis.

Yemen, however, is seeing a sharp rise in Somalis arriving on rickety boats across the Gulf of Aden, with more than 3,700 refugees reaching there so far in August, an earlier than normal start to the traditional peak season for people smuggling across the treacherous waters.

It is testament to the refugees’ desperation that they have chosen to flee to Yemen, which is itself affected by serious unrest, crossing the Gulf on what are often unseaworthy and overcrowded boats, Mr. Edwards said. The crossings claim an annual toll of hundreds as boats capsize and smugglers throw their charges overboard or otherwise brutalize them.

Yemen hosts the second-largest population of Somali refugees in the region, with nearly 192,000, some 15,000 of whom have arrived since January.

Somalia has not had a functioning central government for the past two decades, during which internecine fighting spawned by warlords and Islamic militants has killed countless thousands of people and driven 1.4 million others from their homes, a crisis now compounded by one of the worst droughts in memory.