Character Sketches: Patrice Lumumba by Brian Urquhart

Patrice Lumumba, the first Prime Minister of the independent state of the Congo, was effectively in power for only ten weeks, but he has become a figure of myth and legend — to some a martyr, to others a monster. Under Belgian colonial rule, Lumumba had been a postal clerk and then a beer salesman. He had written an intelligent and even humorous book, Congo, Mon Pays, about the tribulations of his country under Belgium, in which he seemed to see the Congo’s future as a cooperative effort with the Belgians to move from paternalism, tribalism and colonialism to independence and national unity. As a leader of the Mouvement Nationale Congolais (MNC) he was arrested by the Belgians for the first and only time after a noisy demonstration in Stanleyville in 1959, and was released to take part in the hastily summoned Brussels Roundtable that set the scene for the Congo’s independence. As independence approached, he was nominated as Prime Minister.

Lumumba’s first great opportunity came on 30 June 1960, at the Congo’s independence ceremonies. The young King Baudoin of Belgium was the great-grandson of the atrocious King Leopold II, whose rape of the Congo was the ugliest episode in European colonial history. At the independence ceremony, Baudoin made a bizarrely paternalistic speech during which he praised his frightful ancestor’s achievements. Joseph Kasa-Vubu, the Congo’s first President, responded deferentially to the King’s grotesque remarks, giving Lumumba time to turn his own speech into a harsh denunciation of Belgian colonialism. “We have known,” he said, “ironies, insults and blows, which we had to undergo morning, noon and night because we were blacks.” Lumumba’s speech fired the abject spirits of the Congolese with a sense of indignation at their colonial past and he became overnight the true national leader. The Belgians were horrified. They had made absolutely no effort to prepare the Congolese for independence in the belief that after it took place, things would go on very much as before. Their new Prime Minister clearly had no intention of letting that happen.

Five days after independence, the Force Publique, the Congolese army in which there was not a single African officer, mutinied and threw out its Belgian officers. The leaderless army began to harass and assault the Belgian civilian population, most of whom fled the country in panic, leaving the vast territory without administration or security. The result was anarchy. The Belgians sent in paratroopers, ostensibly to protect the remaining white population but, as the Congolese saw it, to reestablish Belgian rule. A confused series of battles in most of the major cities ensued and just ten days after independence the chaos was compounded by the secession, with Belgian connivance, of the Congo’s richest province, Katanga.

After failing to get President Eisenhower to send in the U.S. Marines, Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu turned to the United Nations for help, and the Security Council voted to authorize a large peacekeeping force to get the Belgian troops out of the Congo and restore at least a minimum of public order and administration. The first 3,000 UN troops, from African countries, arrived within three days, followed by 10,000 more in the next two weeks. A large, civilian UN task force filled the void in public administration — airfields, hospitals, communications, central bank, police, etc. — and began to teach the Congolese how to run their country. Ralph Bunche led this wholly improvised operation; I was his chief assistant.

Lumumba proved incredibly difficult to help. He was, understandably enough, bewildered by the avalanche of problems that had descended on his completely inexperienced government. He was intoxicated by unaccustomed power and overstimulated by the world press, which had made him an overnight celebrity. He reacted violently to those who did not instantly agree with him, so that rational discourse was virtually impossible. He showed no interest in the essential hard work of government — only in the politics and publicity of it. He often seemed, as Bunche put it, to be “God’s angry young man.”

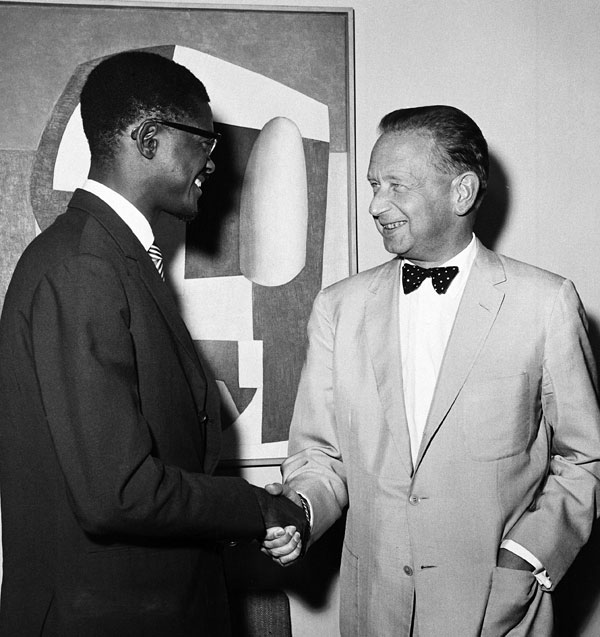

Prime Minister Lumumba's visit to UN Headquarters led to the deployment of the UN Operation in the Congo (known by its French acronym ONUC), which marked a milestone in the history of United Nations peacekeeping in terms of the responsibilities it had to assume, the size of its area of operation and the manpower involved.

In conversation, Lumumba was mercurial to an extraordinary degree. He would threaten violent retribution one minute and plead for vast and diverse quantities of aid the next. He seemed to believe that armed force would solve his major problems — the presence of the Belgian troops or the secession of Katanga — although his own army was incapable of any coherent action, and the UN peacekeepers were forbidden to use force or to interfere in internal Congolese matters. Lumumba was furious when he discovered that the UN was going to get the Belgian troops out of Katanga by negotiation and was not going to subdue secessionist Katanga by force. At one point, he asked me angrily why Hammarskjöld had sent "ce nègre Americain” (Ralph Bunche) to the Congo. I replied that Hammarskjöld had sent the best man in the world for dealing with this kind of mess and that he should consider himself very fortunate to have him. He did not return to this subject.

Lumumba’s lack of patience, experience or common sense was made more dangerous by his formidable powers as a demagogue. His threats, usually repeated over the national radio, could result in large, hostile demonstrations as well as in physical attacks both on the UN people who were trying to help him and on the constantly expanding group of his domestic opponents. He seemed determined to surround himself with tension, fear and resentment.

The Soviet Union had a very large embassy in Leopoldville, and there could be little doubt that their intention was to dominate the Congo through Lumumba. Soviet “advisers” kept popping up in unexpected corners of the capital such as the central police station or the telephone exchange. The western media began to call Lumumba a Soviet stooge, a view enhanced later on by his appeal for Soviet military aid and by the arrival at his political base, Stanleyville, of eleven Soviet transport planes bearing the inscription “Republique du Congo” and the Congolese flag. In fact, Lumumba was a fervent nationalist with little interest in ideology and no particular leanings toward the Soviet Union or anyone else. He was the quintessential loose cannon, willing to accept help from any source willing to provide it. One of his later tirades provided a good example of his state of mind. Threatening to expel the UN by force from the Congo because we had refused to make war on his opponents, he declaimed, “S’il est nesséssaire de faire l’appel au diable pour sauver le pays, je le ferai sans hésitation, persuadé qu’avec l’appui total des Soviets, je sortirai malgré tout victorieux.” The Soviets would have found it impossible to tolerate such a leader for long, but the other superpower relieved them of the necessity for this difficult choice. In early September, after Lumumba had called for Soviet military assistance, the CIA was authorized to assassinate him and to encourage all plots against him. However, the CIA’s half-hearted assassination attempts were frustrated by the UN guards protecting Lumumba’s residence.

As Lumumba became progressively more irrational, he would fly into a rage at the smallest difference of opinion or imagined slight. Some said he was on drugs, others that he was being manipulated by the disreputable cabal of self-appointed foreign advisers who had attached themselves to him. These included a Guinean courtesan (Madame Blouin), a Yugoslav quack, a super-radical French expatriate, and a crazy Ghanaian ambassador. He cut off all contact with Hammarskjöld and Bunche after Hammarskjöld refused to take him along when he led the first UN troops into secessionist Katanga. ( Lumumba’s presence would certainly have aborted the expedition and probably have got himself and Hammarskjöld killed as well.)

What little real power Lumumba had he used disastrously. In an effort to put down a secessionist movement in Kasai province (“the Diamond State”) and then to invade Katanga, he used the Soviet transport aircraft to lift units of the totally disorganized Congolese army into Kasai. In the absence of any logistical arrangements, the soldiers had to live off the land. Looting and rape degenerated into a massacre of the Luba people, the most successful and advanced of the Congo’s two hundred tribal groupings. Not surprisingly, the Luba became Lumumba’s fiercest enemies.

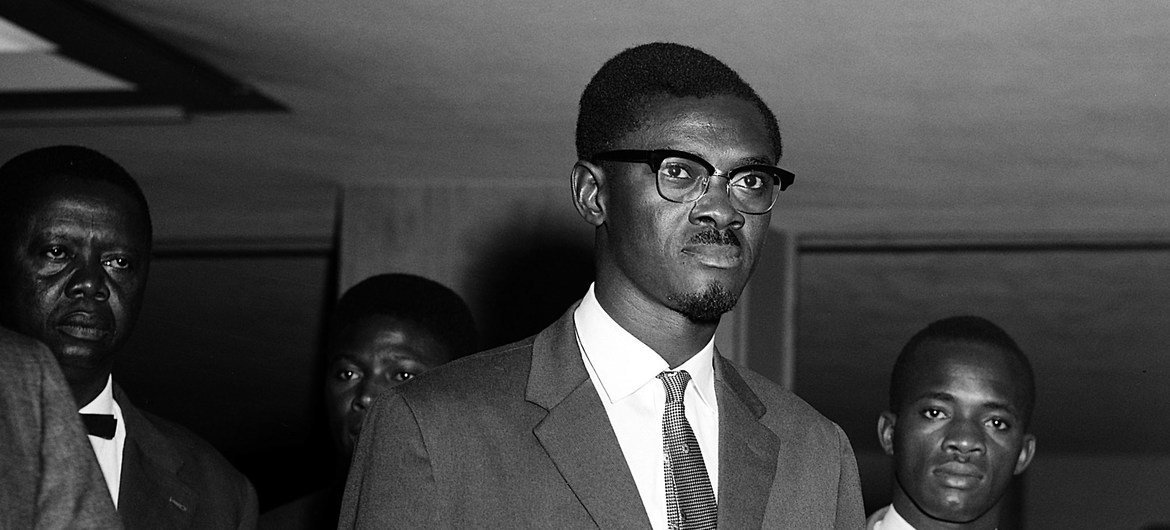

26 January 1960 – Bringing together Congolese and Belgian political leaders and representatives, the Round Table Conference in Brussels was aimed at reaching agreement on ending the European country’s colonial rule of the Congo. Its results included agreement on setting 30 June 1960 as Congo’s date for independence. Patrice Lumumba had been imprisoned ahead of the gathering due to his arrest in connection to a riot in the eastern city of Kisangani, but was released and allowed to attend the conference. Shown here, in the Belgian capital, he raises his arms to show his injuries from being shackled. Photo: Harry Pot, Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, Rijksfotoarchief

24 July 1960 – The issue of the Congo was a top priority for the international community in the early 1960s, with the Security Council discussing the topic regularly. Soon after becoming his country’s first Prime Minister, Lumumba travelled to UN Headquarters in New York. He had stated that the purpose of his trip was to establish direct contact with UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld in order to find a speedy solution to the problems facing his country. Here, he is seen exchanging views with Ambassador Omar Loutfi of the United Arab Republic, shortly before a wider meeting on the Congo. UN Photo

25 July 1960 – There was strong media interest in the Congo. Shown here, flanked by colleagues, Prime Minister Lumumba (third from left, at desk) answers questions during a press conference at UN Headquarters. UN Photo

15 February 1961 – Lumumba’s death while in captivity, along with two colleagues, drew condemnation from around the world. At a Security Council meeting held in the wake of the announcement on his passing, Secretary-General Hammarskjöld said, “I wish to express our deep regret at the assassination of Mr. Lumumba, Mr. Okito and Mr. Mpolo. What has happened is is a revolting crime against principles for which this Organization stands and must stand.” Shown here, Slovenian youth in the city of Maribor attend a protest over Lumumba’s death. (Photo by Danilo Škofiè)

16 January 2015– Lumumba’s legacy has been commemorated throughout the world. Shown here is a statue in the middle of the Lumumba Boulevard in Kinshasa, the capital of the what is now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Speaking at the Security Council meeting held after the announcement of his death, Morocco’s Permanent Representative to the UN, Ambassador Ben Aboud said, “Alive, Patrice Lumumba personified the ideal of his people; now that he is dead, he offers the finest example of sacrifice: his unshakable tenacity and his devotion to his mission, which we shall all defend, shall guide all of us.” UN Photo/Abel Kavanagh

This atrocity finally aroused President Kasa-Vubu and, with American encouragement, he dismissed Lumumba for governing arbitrarily and plunging the nation into civil war. Lumumba responded, also on the radio, by dismissing Kasa-Vubu and calling on the people of the Congo to rise up and the Congolese army to die with him. Since the West supported Kasa-Vubu and the Soviets backed Lumumba, the Congo was now divided on Cold War lines with the UN operation in the middle. Our already herculean task of keeping the country running and preventing civil war became nearly impossible.

A few days later, matters were further complicated by the defection of Lumumba’s chief of staff, Colonel Joseph Mobutu. Mobutu, at the urging of the Americans, announced on the radio that he was taking over the government with a “commission of technicians,” and allied himself with Kasa-Vubu. He thus became the effective, if illegitimate, head of government.

Lumumba, protected by a battalion of UN troops, continued to live in isolation in the Prime Minister’s residence, but his days of power were over. When the UN General Assembly, under intensive American pressure, voted to recognize Kasa-Vubu and Mobutu as the legitimate occupiers of the Congolese seat in the UN General Assembly, he knew the game was up. On 25 November 1960, during a tropical downpour, hidden in the back of a car, Lumumba secretly left the safety of the his residence and set out to drum up support in the rest of the country on his way to his personal power base in Stanleyville. The UN force, which was not allowed to interfere in internal Congolese politics, was ordered neither to assist nor to interfere either with Lumumba’s progress or with the movements of his pursuers. This was a fatal decision. At Mweka, in the vast territory or Kasai, Mobutu’s soldiers caught up with him. He was imprisoned in the military camp at Thysville, half way between Leopoldville and the Atlantic.

Even in captivity, Lumumba’s undoubted charisma made Kasa-Vubu and Mobutu, and perhaps also the United States and Belgium, nervous. Thus, while Hammarskjöld and his representatives demanded his release, Kasa-Vubu and Mobutu, with the help of their Belgian mentors, searched for a way to get rid of him for good. Their essentially simple plan was to hand him over to the Luba people of Kasai, who wanted revenge. (The Luba leader, Albert Kalonji, had vowed to make Lumumba’s skull into a flower vase.) The idea was to land Lumumba at Bakwanga in Kasai and let the Luba do the rest, but at the last minute the plotters found out that UN troops were in charge of the Bakwanga airfield. Lumumba and his two companions, Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo, were therefore redirected to Elizabethville, in Katanga. Kasa-Vubu telephoned the Katanga secessionist leader, Moise Tshombe, to tell him that ‘three parcels’ were on the way and that he would know what to do with them. Tshombe at first indignantly refused to have anything to do with the plot and said he would not allow the aircraft to land in Elizabethville. (Tshombe wisely recorded this conversation, and later on he played the tape to me.) However, under strong Belgian pressure, he finally agreed that the plane carrying Lumumba could land at Elizabethville.

On the aircraft, the specially picked Luba guard worked over their hated enemy with such brutality that the Belgian air crew locked themselves in the cockpit. After landing at Elizabethville, the plane was directed to a remote corner of the airfield, some three hundred yards from the nearest UN post — a Swedish non-commissioned officer and five soldiers. Through their binoculars the UN soldiers got the world’s last view of the first Prime Minister of the Congo — bloody, bound and blindfolded, dumped on the tarmac with his two companions and then hurriedly driven away.

At an isolated house in the bush, Katanga ministers and some Belgians subjected what was left of Lumumba to further beatings. Lumumba, Okito and Mpolo were then driven to a remote area, executed and buried in shallow graves. The next day the bodies were exhumed, cut up and dissolved in sulphuric acid. No identifiable trace of Lumumba and his companions remained. Patrice Lumumba was thirty-six years old.

Tshombe and his Belgian handlers assured the UN that Lumumba and his companions were being well taken care of, although, not surprisingly, they refused any access to them. The announcement — nearly a month later, by Godefroid Munongo, Katanga’s sinister Minister of the Interior — that Lumumba had escaped and had been caught and killed by the people of a “loyal village,” was universally disbelieved. It triggered a violent worldwide reaction. Belgian and American embassies were attacked, and there was a riot in the spectator’s gallery of the UN Security Council. Hammarskjöld became the whipping boy of the radical left in many countries and was denounced by the Soviets as an accessory to the murder.

The assassination of Lumumba was a brutal and squalid atrocity. It was engineered by Mobutu and by the Belgian government in an effort to re-establish their influence and to protect its interests in the Congo. The assassination was condoned by the United States, which feared that Lumumba was becoming an African Fidel Castro. The UN, with its policy of non-interference in the internal politics of the Congo, failed to rescue Lumumba at the one point — his arrest at Mweka -- when it might possibly have been able to do so. Nobody comes out well in this story.

To this day, especially for oppressed minorities, Lumumba stars as a martyr to colonialism and to Western capitalism and greed. The real-life Lumumba, as seen by those who tried to help him, arouses little interest. A courageous, intelligent, unstable, and inexperienced young man went disastrously wrong. Lumumba had no training for public responsibility, and when power and celebrity suddenly came to him, the chaotic situation in the Congo and his own personality together proved too much for him. Although he was undoubtedly sincere in his quest for Congolese national unity, he had no practical idea how to get there, nor the patience and discipline necessary to move toward such a difficult goal. He had no interest in the laborious work of effective government and demanded instant results and solutions. He was oblivious to the human consequences of his actions. If he had had the time and the power, he might well have become the worst of tyrants.

None of this is any excuse for those who conspired so successfully to kill him.