Character Sketches: Trygve Lie by Brian Urquhart

"Welcome, Dag Hammarskjöld, to the most impossible job on this earth.” With these encouraging words, Trygve Lie, the first Secretary-General of the United Nations, greeted his successor, Dag Hammarskjöld of Sweden, at Idlewild airport in New York on April 9, 1953.

Lie had certainly had a difficult time since his appointment as Secretary-General in early 1946. “Why,” he asked in his memoirs, “has this awesome task fallen to a labor lawyer from Norway?” Lie had battled through endless frustrations and difficulties only to find himself in the end assailed by the Soviet Union on the left, and by the machinations of Senator Joseph McCarthy and others on the right. He resigned in November 1952.

Lie was the Minister of Justice in a Socialist government in Norway just before the Second World War. His chief claim to international fame up to that time had been granting Leon Trotsky asylum in Norway and rescinding it a year later on the grounds that Trotsky, by his public statements, had violated the conditions of asylum. Trotsky subsequently left Norway for Mexico, where he was assassinated. Lie’s enemies put it about that he had bowed to Soviet pressure, an allegation that stuck to him in his later career. When Germany invaded Norway in 1940, Lie was credited with ordering all Norwegian ships at sea to sail to British ports. He then escaped to London with King Haakon and served throughout the war as foreign minister of the government-in-exile. When the United Nations was being set up in London in late 1945, Lie, as the foreign minister of a fighting ally which was also well-regarded by the Soviet Union, was a useful candidate for high-level UN appointments that required Soviet approval.

The Secretary-General of the UN is nominated by the Security Council and appointed by all the member states in the General Assembly. Various glamorous candidates for the post had been mentioned in the press, including General Dwight Eisenhower, Lester Pearson of Canada, and Anthony Eden of Great Britain, but there was no possibility that the Soviets would agree to any of them. The Security Council nominated Lie as a compromise candidate in early 1946. During the process of Assembly approval, Edward Stettinius, the United States Secretary of State, rushed to my table in the Assembly hall and asked me to identify Lie, whose name he mispronounced to rhyme with ‘tie’ rather than ‘see.’ I pointed out the substantial figure of the Foreign Minister of Norway, and Stettinius then mounted the podium to acclaim Lie as an celebrated wartime leader, a household name, etc.

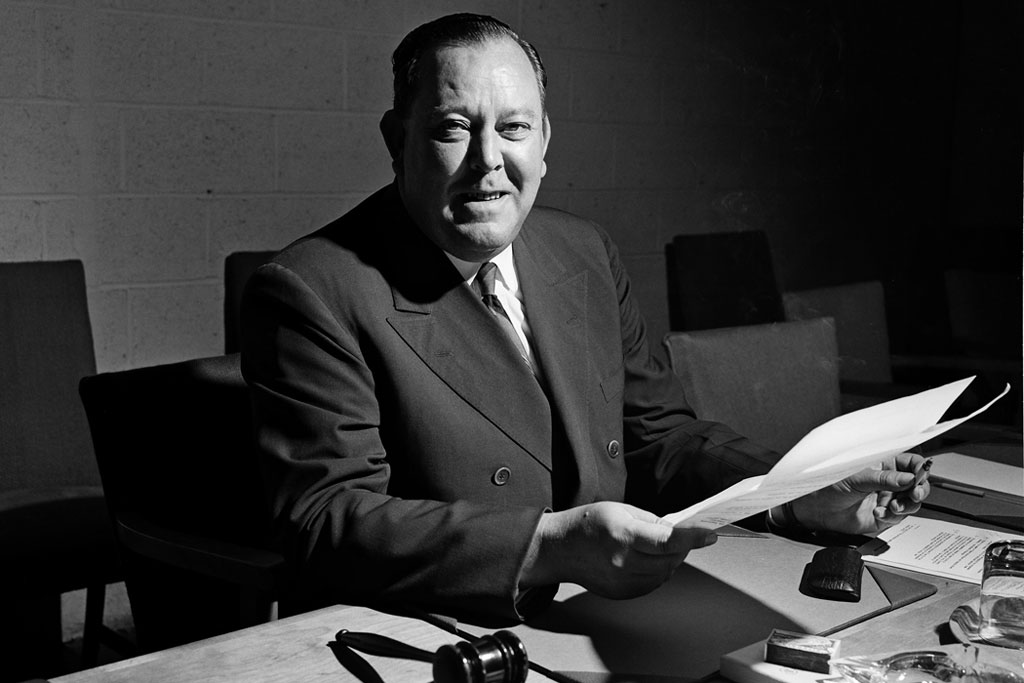

Some highlights from the career of Trygve Lie, the Norwegian politician and diplomat who served as the first elected Secretary-General of the United Nations.

Lie’s appointment as Secretary-General was an anti-climax – the first of many to be suffered by the new world organization. He was suited neither by temperament nor intellect to his very demanding new position, and from the beginning he seemed to be out of his depth in a complex and very public job. Lie relied more on what he called his ‘political nose’ than on intellectual effort or hard diplomatic work, and he was difficult to help or to work for. In public life at any rate, he was a suspicious and insecure man with a hair-trigger temper. He was sensitive about his new position without knowing quite what to make of it. He would leave a public event if he felt he had not been properly seated. At a dinner Gladwyn Jebb gave for Anthony Eden, Lie popped into the dining room before dinner and changed the place cards to give himself the place of honor.

In those early days, most governments were determined to keep the Secretary-General out of politics and to confine his work to administration. Lie did his best both to get the UN going and to work for political moderation and common sense, two qualities that were becoming increasingly rare among governments. Having put Lie in a new and extremely challenging job, the UN’s member governments did little or nothing to provide the qualified, top-level assistance that would have lightened his burden. The eight assistant secretaries-general were political appointees and, except for Arkady Sobolev of the Soviet Union, they were at best mediocre and at worst grotesque. Outstanding in the latter category was the US appointee ‘Potato Jack’ Hutson, whom the Department of Agriculture had evidently been delighted to get rid of. Lie, who met with this dismal crew once a week, was increasingly frustrated and disgusted, and he had every right to be.

Lie’s Secretary-Generalship was not without moments of farce, even of slapstick. In the summer of 1946, we went to Geneva for the final conferences of the League of Nations and the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), the immense, American-led reconstruction operation that began to put the war-shattered world on its feet again. UNRRA was headed by Fiorello LaGuardia, the famously eccentric former mayor of New York City. In the ghastly Palais des Nations in Geneva, former home of the League of Nations, there is a small private elevator originally intended to take the president of the League of Nations Assembly to the podium of the Assembly Hall. On the way to the UNRRA meeting, Lie and LaGuardia, whose combined weight must have approached 500 pounds, both claimed this small and uncertain vehicle as their personal right. Neither would give way and, against all advice, they squeezed into it together. When the doors closed on the competitive statesmen, the elevator, instead of rising, descended slowly out of sight. In the stricken silence that followed, multilingual imprecations arose from the depths. Tweedledum and Tweedledee came to mind. A Swiss engineer was summoned, and the elevator was cranked up to its original position to release its disheveled cargo. The conference started late.

It was due to Lie and his good relations with New York Mayor William O’Dwyer, the Rockefeller family, and Robert Moses, the powerful New York City planner, that after wandering in the wilderness and being threatened with a number of totally unsuitable sites in the United States, the UN was finally settled in its magnificent permanent location on the East River in New York City. This was a major achievement, and Lie deserves all credit for it.

Lie and Herbert Evatt, the Australian foreign minister who was president of the UN General Assembly’s 1948 session, were intensely suspicious of each other. For the 1948 session in Paris, our offices were flimsy temporary structures erected for the occasion in the cavernous space of the Musée de l’Homme, looking across the Seine to the Eiffel Tower. One day, after a shouting match in Evatt’s office, Lie emerged red in the face with rage and slammed Evatt’s door with all his strength. The walls of Evatt’s office then collapsed, leaving the two statesmen glaring at each other over the ruins. Bill Stoneman, a veteran war correspondent who had become Lie’s speechwriter, and I were overcome with laughter by this spectacle, which united Evatt and Lie in rebuking us for lack of respect.

By mutual consent, I left Lie’s office in 1950. I had strongly disagreed with his attitude to the Palestine problem, rightly or wrongly believing him to be seriously biased in favor of Israel. I also thought that some of the things he said and did at Headquarters were putting Ralph Bunche, who had become the UN Mediator in Palestine after Bernadotte’s assassination, at personal risk as well as undermining his work.

Since his resignation in 1952, Lie has often been judged and found wanting, but this is scarcely fair. He had been given one of the world’s most difficult jobs—a job to which he had neither aspired nor sought. He did not have all the qualifications or the charisma that would certainly have helped him, but then whom with such qualities could have been accepted by both East and West? The Soviets and the French, for example, as they would later demonstrate with Lie’s successor, Dag Hammarskjöld, had no wish to have a brilliant and charismatic leader in the Secretary-General’s chair.

1 August 1949 - Before being appointed Secretary-General in 1946, Trygve Lie served in a variety of roles in Norwegian politics, including as Minister of Justice and of Commerce, and, subsequently, as Minister of Foreign Affairs throughout the Second World War. It was in this role that he represented Norway at the first session of the UN General Assembly.

3 May 1945 - Lie’s work with the United Nations before becoming Secretary-General included chairing Commission III which was responsible for drafting the Security Council provisions of the UN Charter. Shown here, Lie chairs a Commission III meeting, held at the San Francisco Conference between 25 April and 26 June 1945.

10 January 1946 - The first session of the General Assembly opened at Central Hall in London, in the United Kingdom. Lie headed the Norwegian delegation to the gathering which, on 1 February 1946, elected him as the first Secretary-General of the United Nations. Shown here, Lie (seated at right at the podium) listens as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Clement Attlee, addresses the General Assembly.

25 May 1946 - The first meeting of the second session of the UN Economic and Social Council had representatives from Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, France, Greece, India, Lebanon, Norway, Peru, Ukraine, the U.S.S.R. the United Kingdom, the United States and Yugoslavia, as well as Secretary-General Lie.

2 October 1946 - Here, Secretary-General Lie (at head of table) confers with senior officials at the temporary headquarters of the United Nations, located at Lake Success on Long Island in New York state. Lie played a role in helping secure the permanent headquarters location on Manhattan in New York City. Seated to Secretary-General Lie’s right is Brian Urquhart, then serving as the Secretary-General’s personal assistant.

25 March 1947. Here, Secretary-General Lie receives from John D. Rockefeller III, on behalf of his father, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., a check for $8,500,000 for the purchase of a six-block site facing the East River on the Manhattan site where the United Nations was to locate its permanent Headquarters.

5 October 1949. The UN Headquarters complex is located in the heart of New York City on 1st Avenue between 42nd and 48th Street. The 18-acre site has been declared international territory and belongs to the 193 Member States of the United Nations. Here, Secretary-General Lie and members of the Headquarters Advisory Committee are seen with the UN flag before it is unfurled atop the completed steel work for the 39-story UN Secretariat building in accordance with the custom of construction workers in 1949.

24 October 1949 - The cornerstone of the UN’s permanent headquarters was laid in 1949, on United Nations Day, during a special open-air General Assembly meeting. The ceremony, which also marked the fourth anniversary of the Organization, was attended by US President Harry S. Truman. Secretary-General Lie deposited copies of the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the cornerstone. Here, he and the building’s chief architect, Wallace K. Harrison, apply mortar to seal the cornerstone.

9 May 1951 - Here, Secretary-General Lie meets with the Prime Minister of Israel, David Ben-Gurion, during the latter’s official visit to UN Headquarters, and accompanied by Israeli and UN officials, including Dr. Ralph Bunche (third from right), the Director of the UN’s Division of Trusteeship, and former Acting Mediator in Palestine.

10 November 1952 - Standing at the presidential rostrum in the plenary hall of the new General Assembly building, Secretary-General Lie reads to the delegates the text of the letter in which he submitted to the President of the Assembly his resignation from his post.

9 April 1953 - Secretary-General Lie’s successor was Dag Hammarskjöld of Sweden. Here, at Idlewild Airport, Secretary-General Lie welcomes Hammarskjöld as he alights from his flight from Stockholm. Famously, Lie told Hammarskjöld that he was about to take over “the most impossible job in the world.”

27 April 1953 - At a ceremony, the City of New York paid a special farewell to Secretary-General Lie on his impending departure, and, at the same time, officially welcomed Dag Hammarskjöld as his successor. Here, Mayor Vincent Impellitteri, on behalf of the City, presents a special scroll to Secretary-General Lie "for distinguished and exceptional public service, " and also awarded him the City's "Medal of Honor."

Lie had political courage and conviction, and he certainly cared passionately about the United Nations. He fully backed the Security Council’s decision to fight the North Korean invasion of South Korea and thus earned excommunication by the Soviet Union. He got into difficulties in trying to deal with Senator Joseph McCarthy’s witch-hunt for American Communists in the UN secretariat, thereby earning the scorn of many of its members. Lie was not a good administrator—the ‘political nose’ did not function well in administration—but his major achievement was in the administrative field. It was due to Lie and his good relations with New York Mayor William O’Dwyer, the Rockefeller family, and Robert Moses, the powerful New York City planner, that after wandering in the wilderness and being threatened with a number of totally unsuitable sites in the United States, the UN was finally settled in its magnificent permanent location on the East River in New York City. This was a major achievement, and Lie deserves all credit for it.

Lie resigned in order, as he put it, to hand over to someone who had the support of all the member states. He was furious when that person turned out to be Dag Hammarskjöld, who was not only a Swede but also had gifts of intellect and character that Lie lacked. In his anger, Lie foolishly began to put it about that Hammarskjöld was homosexual. The only people who took this canard seriously were the FBI, prompted by Lie’s crony and UN security chief, Frank Begley. The FBI reported triumphantly to Washington that the new Secretary-General was living with his boyfriend in a suite at the Waldorf Astoria. The ‘boyfriend’ was Hammarskjöld’s chief assistant, Per Lind, a respected Swedish diplomat and father of four. When this report was referred to Walton Butterworth, the American ambassador in Stockholm, he commented that if the US government was capable of being taken in by such prurient nonsense, they didn’t deserve to get Hammarskjöld as Secretary-General. Lie’s performance outraged Lester Pearson, the foreign minister of Canada, and Gladwyn Jebb, the British ambassador, who told him that if he did not stop slandering his successor they would have to take public action. Lie’s malicious and baseless calumnies would dog Hammarskjöld at controversial points in his subsequent career.

This was an unworthy end to Lie’s time at the UN, and it tended to color subsequent estimates of his performance. He had done his best when the exigencies of the incipient Cold War placed him in an historic position at an historic time, but the UN lost much of its original spark through Lie’s haphazard appointment.