Character Sketches: Ralph Bunche by Brian Urquhart

I worked with Ralph Bunche for nearly 20 years, day and night, in good times and in bad. He was one of the closest friends I ever had. I wrote his biography, was the executor of his papers, have given many talks and lectures about him and worked on a documentary film of his life, but I still feel that there is something more to be said about this memorable but insufficiently remembered man.

Ralph Bunche was the least obvious person I ever met. When I began to write his biography more than ten years after his death, I assumed that I knew a great deal about him. When I started to look into his papers, I found that I knew virtually nothing about his career before he came to the United Nations and had only a superficial idea of much of his achievement thereafter. Genuine modesty and an unfailing sense of discretion had prevented him from talking, even to me, about his remarkable career or from boasting, as most public figures do, of their personal triumphs. He just preferred to talk about other things.

Bunche’s discretion, honesty and respect for confidentiality inspired universal confidence. People might disagree with him, but they always trusted him. He never paraded inside knowledge or solicited public acclaim. He believed that results, not personal credit, were what mattered. When he was told that he had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, he wrote a letter to the Nobel Committee refusing the prize on the grounds that he had been simply doing his job as a UN civil servant.

Only after his Norwegian boss, UN Secretary-General Trygve Lie, insisted that the prize would be a credit to the United Nations, did he agree to accept it. In the 1960s, the University of Chicago Press asked his permission to publish one of the monographs that he had written in 1939 as the basis for Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma – virtually the first draft of much of that historic work. Bunche indignantly refused permission to publish the monograph, saying that it would be unfair to Myrdal. It was finally published after his death.

I can think of few people who have a comparable record of lasting historical achievement. As a black intellectual in the 1920s and 1930s, Bunche had formulated much of the intellectual and practical basis of the later civil rights movement. With A. Philip Randolph, he founded the National Negro Congress because they thought that the NAACP was, at that time, too middle-class to give a voice to the majority of the black population. With Randolph and others, he conceived the 1941 March on Washington to protest the lack of fair and equal employment for Negroes in war industries, an action that is widely held to be the beginning of the modern civil rights movement. (The march was called off when President Franklin Roosevelt issued an Executive Order banning racial discrimination in defense industries and setting up the Fair Employment Practices Commission.)

Bunche was an early scholar of colonialism and researched the subject in the field in Togo, French Cameroon, South Africa, Uganda and Kenya. In his 1936 A World View of Race, he drew a striking parallel between colonialism in the world at large and racial discrimination in the United States. He was the founding director of the Political Science Department at Howard University in Washington. He served in the OSS during the war and had a major influence on the treatment of racial problems in the US army, as well as writing manuals for the troops on how to behave in Africa and how to deal with different perceptions of race in foreign countries.

Some highlights from the career of Ralph Bunche, a long-serving UN official who went on to become a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate for his efforts to bring peace and stability to the Middle East.

Bunche’s knowledge of colonial problems brought him into the State Department (its first black official) on the team that was drafting the UN Charter. There and at the San Francisco Conference, he was the main drafter of Chapters XI and XII of the Charter, on Non-Self-Governing Territories and the Trusteeship System. In the fledgling United Nations he set up the Trusteeship System and was also a dynamo for decolonization – a transition that was supposed to take 100 years but was largely completed in less than 25. Ralph’s activism certainly did much to accelerate this historic process.

Bunche also became one of the world’s foremost experts on Palestine. As the mentor of the 1947 UN Special Commission on Palestine, he wrote both the UN Partition Plan for Palestine, which was approved by the General Assembly, and the minority federation plan. (The situation might be very different today if in 1948 the Arabs had accepted the Partition Plan, which provided for a Palestinian State far larger and more viable than anything the Palestinians can now possibly hope for, as well as an economic union of the two States that would have ensured at least some degree of economic parity.) Bunche conceived, built up, and directed the UN’s first peacekeeping operation, the UN Observer Group in Palestine, and wrote the plan submitted by the UN Mediator, Count Folke Bernadotte, for the implementation of the partition of Palestine.

When Bernadotte was assassinated by the Stern Gang in Jerusalem in September 1948, Bunche took over as Mediator. He negotiated the armistice agreements between Israel and her Arab neighbours, the only written Arab-Israel agreements for 30 years and the foundation of whatever peace there was during those years in the Middle East. Bunche was under no illusions about his success in Palestine. “This problem,” he wrote in 1947, “can’t be solved on the basis of abstract justice, historical or otherwise. Reality is that both Arabs and Jews are here and intend to stay. Therefore in any ‘solution’ some group, or at least its claim, is bound to get hurt.” And in 1957, when the world was applauding the UN’s – and Bunche’s – success in setting up a peacekeeping force in the Middle East after the Suez crisis, “…there can be no peace or real progress toward peace in the Near East until the problem of the Arab [Palestine] refugees is solved. The world evades that one.”

Bunche was the architect and director of subsequent United Nations peacekeeping operations, and he personally led the largest and most challenging of these, the 1960 UN operation in the Congo. Until his death in 1971, he was the international negotiator and mediator most in demand all over the world. As his friend U Thant put it in his funeral oration, Bunche was “an international institution in his own right.” He was, and remains, the preeminent model of the selfless but dynamic public servant.

In a lesser man such a record might well have led to arrogance and complacency; in Ralph the opposite process took place. As I said at his funeral, the grander he got the nicer he became. He remained as he had always been – down-to-earth, humorous, kindly, and unpretentious. He continued to be more concerned with achieving results than with getting the credit for them, more interested in real people than in celebrities, more moved by the struggles of the young and the disadvantaged than by the whims and favours of the great and famous. In all the frustrations of the Cold War he never wavered in his belief that the United Nations could, and must be made to work and to realize the great aims of the UN Charter as a practical reality.

Ralph was not an easy man. He made no concessions to mediocrity or sloppy thinking. He was ruthless with any sign of disloyalty to the United Nations, or with anything that he regarded as improper or dishonest behaviour. He was a shrewd judge of character and could spot a phony a mile away. He instantly saw through slick but unsound ideas. He strongly resisted pressure from any government, especially his own. He was totally loyal to the three Secretaries-General he worked with, and although he was certainly aware of their weaknesses, he kept his opinions to himself. He was the only UN official whom Dag Hammarskjöld regarded as an equal. Of Hammarskjöld he wrote, “I learned more from him than from any other man.”

12 March 1947 - Ralph Bunche had been an academic and a staff member of the US Department of State in the 1930s and early 1940s, which brought him into contact with the then-forming United Nations. In 1946, UN Secretary-General Trygve Lie “borrowed” him from the State Department and placed him in charge of the UN’s Trusteeship Department to help deal with problems faced by peoples who had not yet attained self-government. Here, the Secretary-General discusses the programme of the first session of the Trusteeship Council with Bunche and another UN official. UN Photo

May - September 1948 – From June of 1947 to August of 1949, Bunche worked on one of the most important assignments of his career – the confrontation between Arabs and Jews in Palestine. He was first appointed as assistant to the UN Special Committee on Palestine, then as principal secretary of the UN Palestine Commission, which was charged with carrying out the partition approved by the UN General Assembly. In early 1948 when this plan was dropped and fighting between Arabs and Israelis became especially severe, the UN appointed Count Folke Bernadotte as mediator and Ralph Bunche as his chief aide. Shown here, Bernadotte (second from left), and other UN officials, including Bunche, brief UN military observers prior to their deployment in the Holy Land. UN Photo

May – September 1948 – The UN Mediator for Palestine, Count Folke Bernadotte, was assassinated in September 1948 and Bunche was named as his successor. After eleven months of virtually ceaseless negotiating, Bunche obtained signatures on armistice agreements between Israel and the Arab States. Shown here, in Haifa, Israel, Bunche confers with the UN’s Chief Military Observer, General A. Lundstromt. UN Photo

19 October 1948 – Alongside members of the Security Council, at a meeting held at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, Bunche – in his role as UN Mediator for Palestine – presents his report to the members. Bunche was a strong believer in the work of mediation. The Nobel Committee later referred to one of his lectures, in which Bunche "speaks of the qualities mediators should possess: ‘They should be biased against war and for peace. They should have a bias which would lead them to believe in the essential goodness of their fellowman and that no problem of human relations is insoluble. They should be biased against suspicion, intolerance, hate, religious and racial bigotry.’” UN Photo

18 April 1949 – Not long after returning to UN Headquarters in New York, Bunche asked the Security Council to relieve him of his responsibilities as Mediator for Palestine since the cessation of the military action and the signing of the armistice agreements made the position redundant. Bunche then took an extended leave before returning to his post as Director of the United Nations Trusteeship Department. Shown here, Bunche confers with Secretary-General Trygve Lie on his first day back at UN Headquarters. UN Photo

02 June 1950 – Amidst the heavy workload on various issues on the international agenda, Bunche also found time for other activities. Shown here, at a garden party at UN Guest House to raise funds for the UN International School, Bunche and his son (third from left), take "friends for a ride." UN Photo

25 September 1950 – Bunche’s role as a peace negotiator in the Middle East led to his being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950. “There are many who figuratively stand beside me today and who are also honoured here. I am but one of many cogs in the United Nations, the greatest peace organization ever dedicated to the salvation of mankind's future on earth. It is, indeed, itself an honour to be enabled to practise the arts of peace under the aegis of the United Nations,” Bunche said in his acceptance speech. Shown here, Ambassador Nasrollah Entezam of Iran, serving as the President of the fifth session of UN General Assembly, congratulates Bunche on his being named a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. UN Photo

09 May 1951 – Bunche’s service with the United Nations brought him into contact with various dignitaries from around the world. Shown here, he joins the President of the General Assembly and various Israeli officials in greeting the Prime Minister of Israel, David Ben-Gurion, during an official visit to UN Headquarters in New York. UN Photo

13 October 1955 – Bunche spent 25 years serving the United Nations and under various Secretaries-General. Shown here, he confers with Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld while on their way to a meeting of the General Assembly's First Committee, which deals with disarmament, global challenges and threats to peace that affect the international community and seeks out solutions to the challenges in the international security regime. UN Photo

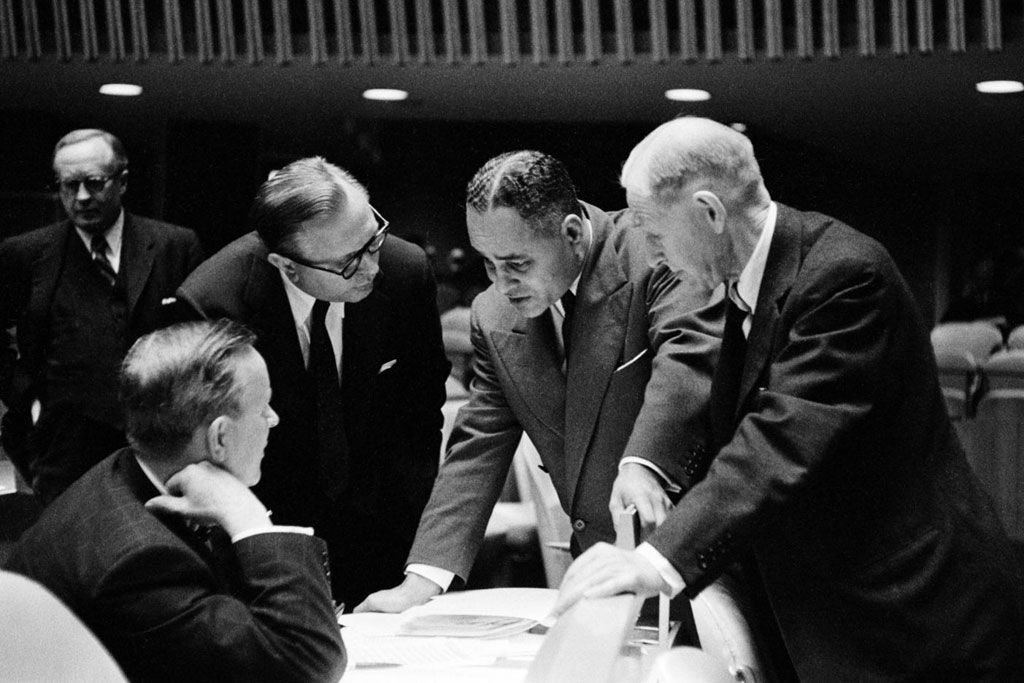

07 November 1956 – The Middle East continued to be a topic on the United Nations agenda throughout the 1950s. Shown here, Bunche confers with the permanent representatives of Norway and Denmark, and Canada’s Secretary of State for External Affairs, Lester B. Pearson (seated at left), ahead of a special General Assembly meeting on the Suez Crisis. At that meeting, two new resolutions – one calling for the immediate withdrawal of foreign troops from Egyptian territory, the other approving the guiding principles set forth by Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld for establishing a UN emergency force – were introduced. UN Photo

16 November 1956 – The General Assembly held its first emergency special session from 1-10 November 1956 on the Suez Crisis. At the meeting, it established the UN Emergency Force (UNEF), the first-ever UN peacekeeping force. Shown here, the chief of UNEF, Major-General E.L.M. Burns of Canada, attends consultations with military representatives from various nations at UN Headquarters concerning the organization of the force. In addition to Bunche attending, in his new role of Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs, also present is Brian Urquhart (seated two seats left of Bunche) of the Executive Office of the Secretary-General. UN Photo

25 March 1957 – Bunche was to later say about his work on the Suez Crisis that it was "the single most satisfying work I've ever done… for the first time we have found a way to use military men for peace instead of war." The Suez Canal had been shut down since hostilities began in Egypt late in October 1956, and part of the response included a UN salvage operation in which a fleet – consisting of Dutch, Danish, Belgian, Swedish, German, Italian and Yugoslav ships – began clearing the waterway. Shown here, Bunche and Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld (taking a photograph), watch the lifting of a sunken tugboat, one of the most difficult obstructions in the canal. UN Photo

23 April 1959 – UNEF was set up to secure and supervise the cessation of hostilities, including the withdrawal of the armed forces of France, Israel and the United Kingdom from Egyptian territory and, after the withdrawal, to serve as a buffer between the Egyptian and Israeli forces. In his role as Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs, Bunche visited the field operation. Shown here, on a six-day trip, Bunche (second from left) is seen at one of the observation posts manned by members of UNEF’s Danish-Norwegian Battalion along the Armistice Demarcation Line. UN Photo

05 August 1960 – Developments in Africa were to feature heavily on Bunche’s agenda in the 1960s. In July 1960, the Security Council authorized UN military assistance to the Republic of the Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), with some 11,500 soldiers from nine countries deployed to help restore order and calm in the country. Secretary-General Hammarskjold sent Bunche as his Personal Representative in the Congo, for talks prior to the arrival of UN troops in the province of Katanga. Shown here, Bunche speaks with Godefroid Monongo, Minister of the Interior of Katanga Province, in Elisabethville (now known as Lubumbashi). UN Photo

25 September 1961 – Bunche's work in the Middle East was recognized widely, including by the US Government, which awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963, the country's highest civilian award. Shown here, Bunche greets President Kennedy, who was at UN Headquarters in New York to address the 16th session of the General Assembly. UN Photo

20 November 1961 – The situation in the Republic of the Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), which was undergoing secession-related violence, remained a top agenda item for the United Nations, with the Security Council meeting to discuss the matter regularly. Shown here, U Thant (left), in his role of Acting UN Secretary-General following the death of Dag Hammarskjold, confers with Bunche, during a Council session. UN Photo

08 April 1964 – Cyprus also became a major topic for the Security Council in light of the island’s inter-communal violence between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs Bunche confers with the President of the Republic of Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios, in the Presidential Palace in Nicosia. The Council had voted to establish a UN peacekeeping force on the Mediterranean island in March 1964. UN Photo

28 August 1964 – Within the framework of the United Nations, the principle of nuclear non-proliferation was addressed in negotiations as early as 1957 and gained significant momentum in the early 1960s. Shown here, Secretary-General U Thant (left) speaks with Under-Secretary-General Bunche at Kennedy International Airport, before departing for Geneva to attend the Third Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy. The structure of a treaty to uphold nuclear non-proliferation as a norm of international behaviour had become clear by the mid-1960s, and by 1968 final agreement was reached on a treaty that would prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons, enable co-operation for the peaceful use of nuclear energy and further the goal of achieving nuclear disarmament. UN Photo

04 December 1964 – Before and during his service with the UN, Bunche remained involved with the US civil rights movement, taking part in events such as the "March on Washington" in 1963 at which civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his historic "I have a dream" speech on racism. Shown here, he greets Dr. King and his wife during a visit to UN Headquarters in New York. UN Photo

01 July 1966 – From the mid-1960s onwards, the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) played an important role in helping prevent further fighting between Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot communities on the island. Shown here, Under-Secretary-General Bunche adjusts his seat belt in a helicopter taking him on a visit to areas where UNFICYP troops are deployed. UNFICYP's responsibilities were expanded in 1974, following a coup d’etat by elements favouring union with Greece and a subsequent military intervention by Turkey, whose troops established control over the northern part of the island. UN Photo

04 April 1968 – Cold War tensions in South-East Asia was another dominant topic on the international agenda in the 1960s. Shown here, US President Lyndon B. Johnson (second from left) sits with Secretary-General U Thant and Under-Secretary-General Bunche (left) at UN Headquarters for discussions on the situation in Viet Nam and the surrounding region. UN Photo

26 September 1969 – The Prime Minister of Israel, Golda Meir, paid an official visit to UN Headquarters and was a guest of honour at a luncheon given by Secretary-General U Thant. Shown here, Mrs. Meir is escorted by Under-Secretary-General Bunche following her arrival. UN Photo

27 February 1972 – Bunche was plagued by a number of health ailments later in life and resigned from the UN because of these. His resignation was not announced because Secretary-General U Thant hoped he would be able to return soon. However, his health did not improve and he died in December 1971 at the age of 68. Shown here, a tribute to Bunche held at UN Headquarters not long after his passing, which was mourned by many in the international community and elswhere. The day was designated as Ralph J. Bunche Day by Governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, in a proclamation read by Jackie Robinson, co-chairman with Sidney Poitier for the event. UN Photo

07 August 2003 – Bunche's achievements, and the example he set for others, have not been forgotten at the United Nations. Shown here is a ceremony at UN Headquarters to remember the man as a champion of peace and idealism about humanity's problems and a towering figure in 20th century history, including the issuance of a set of stamps in his honour, part of a year-long commemoration of the 100th anniversary of his birth. Those attending included his daughter Joan H. Bunche (right), Secretary-General Kofi Annan (third from left) and Brian Urquhart, who succeeded Bunche as Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs. UN Photo

Ralph took a long time to give his confidence to anyone. My first three years with him were a process of arguing, questioning, and generally being tested out. It was the most valuable education I ever had. After this rigorous apprenticeship I entered into a working relationship and a friendship that became a central part of my life. Ralph was a thoughtful friend. When I went to the Indian subcontinent with U Thant in 1965 to try to stop the very menacing war between India and Pakistan, Ralph had my lacklustre office completely refurbished in my absence as a surprise for my return. When I was kidnapped in the Congo in 1961, he stayed up all night in New York orchestrating my release and telephoned my three children at their various schools, so that they would not be alarmed by the sensational press stories about the incident. He was godfather to our daughter Rachel, whom he loved. Even when he was mortally ill and nearly blind, he would still sally forth to buy her the book he thought she would like best for Christmas. During his final days in the hospital, he kept with him the embroidered mat she had made for him.

Until his death in 1971, he was the international negotiator and mediator most in demand all over the world. As his friend U Thant put it in his funeral oration, Bunche was “an international institution in his own right.” He was, and remains, the preeminent model of the selfless but dynamic public servant.

Ralph’s relentless devotion to duty and his very high standards of achievement and behaviour certainly caused major tensions in his private life. At home he was something of a parental tyrant, and his attitude to his wife, Ruth, although he adored her, was often overbearing and sexist by today’s standards. She bitterly resented his many prolonged absences from home, and her letters are full of complaints that she is a virtual widow, left with the sole responsibility for bringing up three squabbling children. Their marriage, together or apart, was certainly fraught with considerable stress, but any idea of separation would have been inconceivable to Ralph. When I told him that my first wife and I were divorcing (amicably so that we both could re-marry), he was genuinely shocked. “Sometimes I just don’t understand you white folk,” he said.

Ralph’s worst shock – and he had many – was the suicide of his daughter Jane, and he never really recovered from it. Such a disaster in their own family was an unimaginable blow to Ralph and Ruth, and it caused him prolonged and bitter soul-searching about his own role as a father. This tragedy, and his rapidly declining health, clouded his last years.

As his last, unpublished writings show, Ralph was deeply disillusioned about what he had previously believed to be decisive progress on the race situation in the United States. What had been a largely Southern problem had become, with the growth of large black ghettoes in the North, a new nightmare, marked during the 1960s by violence and rioting in most of the northern cities of the United States. Appalled as he was at this turn of events, Ralph had no time for the loud and then fashionable ‘Black Power’ leaders, believing them to be strong on rhetoric but lacking any serious plan or ability to improve the lot of the black population of the United States. Bunche was convinced that full integration into American society was the only valid goal, indeed the only practical option, for Negroes and he despised facile, rabble-rousing calls for violence or separatism.

Bunche had been the friend and mentor of many African liberation leaders, but he regarded Patrice Lumumba, whom he had desperately tried to help in the Congo, not as the saint and martyr that many radicals liked to imagine, but as often dangerously irresponsible – a disaster for his own people and a severe setback for African decolonization. Such forthright and farsighted views, as well as his success in the great world, sometimes caused him to be derided as an Uncle Tom by a new generation of young and vocal black radicals who knew nothing of his decisive work for civil rights in the United States and cared little for his views on the future of his own people.

In spite of near blindness, diabetes, kidney failure, and a host of other ills, Ralph stuck to his work and did it remarkably well until, in 1971, he was permanently hospitalized. Because no one could imagine the UN without him, it never seems to have occurred to anyone to reduce his responsibilities, nor, I think, at that stage, did he himself want such respite. Years before, when he announced that he was leaving the UN to devote himself again to the civil rights movement, he had been persuaded by then Secretary-General U Thant, much against his will, to stay on at the United Nations because he was indispensable.

When Ralph died, the world hailed him as an astonishingly effective public servant and intellectual leader. He had been a model for black and white alike, a pioneer in domestic as well as international causes, and he had gained a unique degree of worldwide respect and confidence. After his death, his achievements were remembered, but the achiever was largely forgotten. When I published his biography in 1993, I was surprised to discover that virtually no one, especially African-Americans, knew of his founding role in the civil rights movement; or of the commanding part he had played in bringing about decolonization; or that, as a very sick man, he had marched with Martin Luther King on Washington and Selma and had made remarkable speeches on both occasions; or that his writing on racial problems in the sixties had a relevance and originality which have now become part of the acknowledged wisdom on the subject. I found that most people believed that this warm, humorous and wise man was a cold, faceless international bureaucrat. I was astonished to hear Isaiah Berlin, who had met him in Washington in the 1940s and in Israel, dismiss him, with Oxford omniscience, as “just an Uncle Tom.” Young scholars now studying Bunche’s career are amazed at what they find. He has begun to be appreciated as a 20th century leader who set a standard of behaviour and performance that was admired all over the world, and whose pioneering work in many fields is still of the greatest importance and relevance.

Personally, I remember Ralph best in the small hours of some international crisis, calm, resourceful, unhurried, undismayed, and supremely responsible. I remember his contempt for bigotry, injustice or indecency of any kind. I remember his friendship and his affection for my family. And I remember that no problem, however difficult or intimidating, seemed overwhelming when he was around. Ralph Bunche liked his fellow human beings and devoted his life to helping them to overcome their conflicts and their difficulties.