Interview with former UN official Brian Urquhart (Part 1)

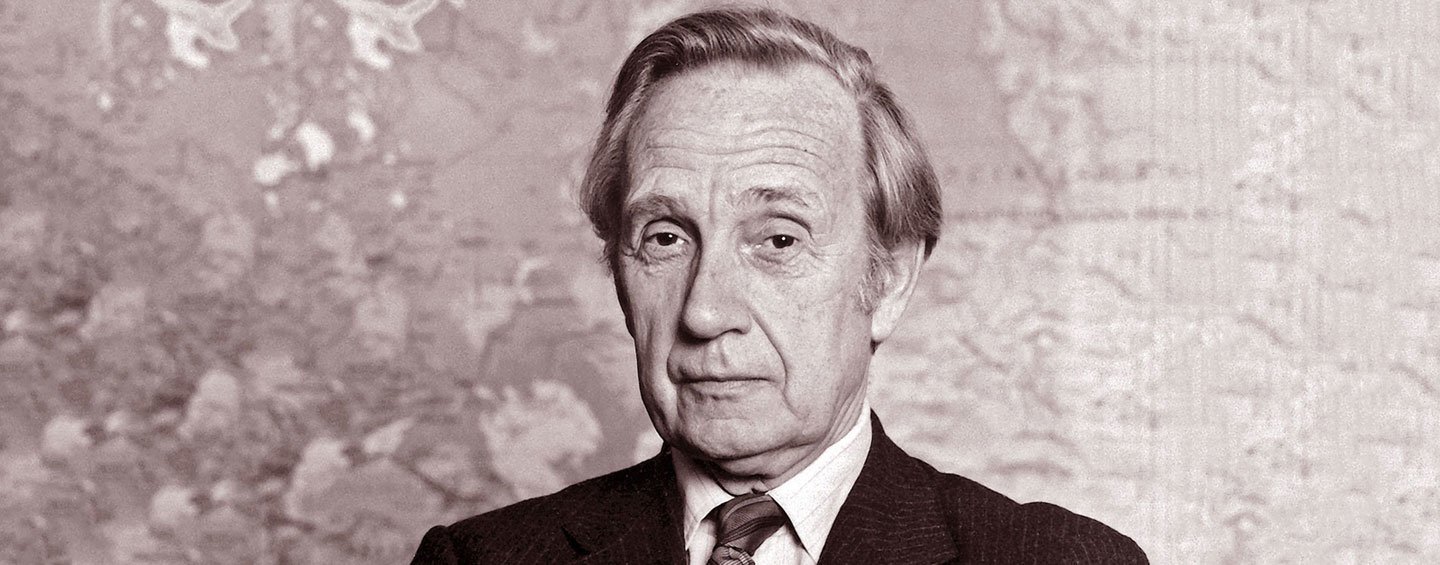

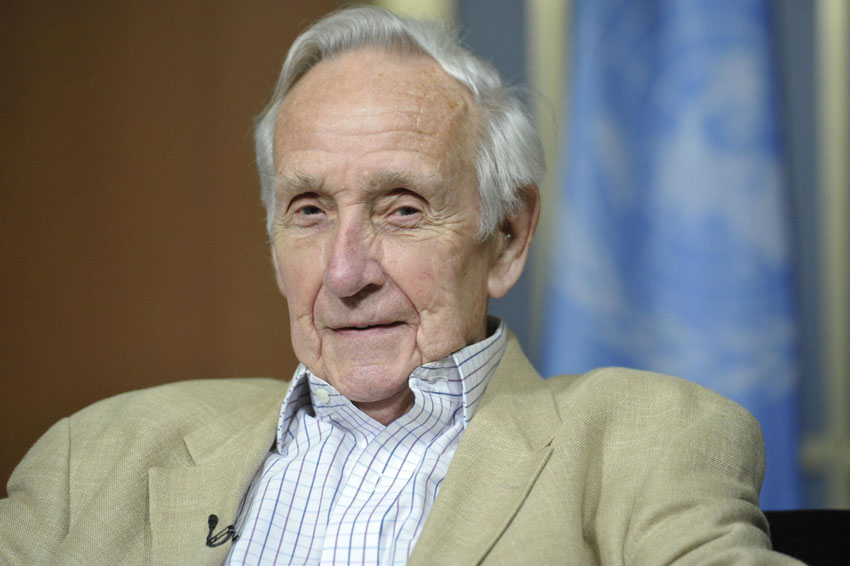

Sir Brian Urquhart, who celebrates his 94th birthday in February, is a living chronicle of a large chunk of 20th-century history.

Throughout his four decades of service to the United Nations, starting as one of its very first staff members and ending as an Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs, he also helped shape history-making moments. He was present for the birth of the United Nations in 1945, and was witness to many of the Organization’s – and the world’s – seminal milestones.

All of these easily amount to a front-row seat on history. But Sir Brian’s links to history go even further. As a youth, his experiences include attending a lecture given by Indian independence leader Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi while in primary school and taking part in the coronation of King George VI.

I had a wonderful time working for the UN. It was quite difficult sometimes, but it was what I wanted to do... I loved the job, I believed in it. I still believe in it.

As a soldier in World War II, he was involved in the surrender of German scientists working in nuclear research; he was one of the first Allied troops to liberate the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp; and he even helped Danish author Karen Blixen, of 'Out of Africa' fame, out of a predicament at the end of the war. To top it off, his role in 'Operation Market Garden' – one of the most well-known military actions of the later stages of the war – was immortalized in an epic film.

As Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said in a tribute message on the occasion of Sir Brian’s 90th birthday four years ago, “You have had an enormous influence on every Secretary-General. Even today, staffers everywhere seek to live up to your example. And you remain one of our wisest and staunchest advocates.”

Here, in the first installment of a two-part feature, UN News spotlights the experiences and views of Sir Brian leading up to the creation of the United Nations.

Sir Brian Urquhart was born in his grandfather’s house in 1919, in Bridport, Dorset, on the southern coast of England, the younger of two sons. Due to a lack of money, between the ages of six and eight, he was enrolled at a school in Bristol at which his mother taught: the Badminton School for Girls. In his autobiography, Sir Brian wrote that international affairs formed a large part of the school’s teaching, describing it as “an excellent school with some very un-English characteristics. Of these one of the most important was a passionate anti-xenophobia.” The school was founded by the sister of Sir Brian’s mother and her partner – Aunt Lucy and Ms. Beatrice M. Bake, two ladies who supported the work of the United Nations’ forerunner, the League of Nations.

UN News: The thrust of your early education seems to have foreshadowed the international path your life has taken. What influence do you think your Aunt Lucy and Ms. Bake had on you?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Absolutely enormous. They were formidable ladies, as was my mother actually. They had a civil belief that the League of Nations ought to work. They didn’t think it would work, because governments weren’t capable of making it work, but they thought something like that had to work. They had a huge influence. Then, of course, we got into World War II, and it collapsed. But I had always wanted to work at the League of Nations. By the time I got there, anywhere near it, of course we had the war so I was in the army instead.

Following an eventual transfer to a preparatory school for boys, at the age of 11 and at the insistence of his headmaster who knew of the financial situation of Sir Brian’s family, he sat for what was then known as the King’s Scholarship exam for Westminster School in London.

He described passing the exam as a “turning point because it gave me affordable access to an ancient and civilized school for the next six years.”

UN News: About your experience in the British schooling system in the 1920s and 1930s, you wrote that “if you were very lucky you received that intellectual stimulus, the essential shot-in-the-arm, that changes the way you think and look at life” and that you fell into that category. Just how important was education for your development?

Sir Brian Urquhart: My father was an extremely unsuccessful painter, actually a rather good painter but he didn’t make any money. So I had to get scholarships, which in those days you got on merit, and I managed to do that.

I went to Westminster which gave a traditional, classical education – that is to say that you learned Greek, Latin and philosophy. My mother thought that was a mistake, so I did foreign languages. I got to the top of that at the age of 15 and I had two years to go [to finish school].

I was lucky I transferred to the history part of the school, which was run by a school-master straight out of Evelyn Waugh: John Edward Bowle. He was an absolutely brilliant, extremely eccentric person who was able, in some extraordinary way; to get one to write; to get one to think about contemporary problems; to read history in a rather personal way and to see how it all came together. I’m very grateful to this remarkable teacher.

Sir Brian’s six years at Westminster School were formative. His schoolmaster, John Edward Bowle, had his students read and discuss contemporary books, and would bring in the authors to address the 16-year-old students. Some of those who spent afternoons engaging the students in discussion on their books included Bertrand Russell, Arnold Toynbee and H.G. Wells. After finishing high school, Sir Brian attended Oxford University as a Hinchcliffe Scholar at Christ Church College. His time at the university coincided with various events in Europe and the world in general, from the Spanish Civil War to the Italian conquest of Abyssinia, which preceded World War II.

UN Secretary-General, Trygve Lie, confers with the Executive Secretary of the Preparatory Commission of the United Nations, Gladwyn Jebb. Sir Brian Urquhart worked for both men. (1 January 1946) UN Photo/Marcel Bolomey

UN Secretary-General, Trygve Lie, confers with the Executive Secretary of the Preparatory Commission of the United Nations, Gladwyn Jebb. Sir Brian Urquhart worked for both men. (1 January 1946) UN Photo/Marcel Bolomey

UN News: You wrote that Westminster School left you with the ingrained idea on the concept of service. How is that?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Well, that was true, you know, almost across the whole British public school system, because the system, as such, was designed to staff a very large empire run by a small, off-shore island. I mean the idea was that unless you were some sort of kind of a genius, like a musician or a painter or a poet or something, you should concentrate on the idea of serving. And it wasn’t a priggish idea – it seems to be not a bad idea really – and I think we were very much brought up to think that unless we displayed some fantastic genius for something, we would be lucky to be in public service, or indeed earlier on, to go into the church – the Church after all is a state religion in England, unbelievably – or to go into the army, to come to that. These were the main sources of public service. I wanted to be a civilian. And, you know, I think it wasn’t a bad idea – although bad luck on all those people we were going to rule over in the colonies – so you trained a whole group of people who would do that, and, incidentally, who would go to some distant part of the world and stay there their whole working life.

UN News: What kind of a student were you?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Well, I had to be very good because otherwise I, first of all, wouldn’t have gotten a scholarship to a public school and then I wouldn’t have gotten a scholarship to Oxford, in which case I would have gone and worked in a bank. So I was quite a good student!

UN News: You were a top student, being awarded scholarships throughout much of your education, but surely it wasn’t all work and no play, was it?

Sir Brian Urquhart: [In 1937] we had at school one son of Joachim von Ribbentrop, who was the German ambassador in London [and Foreign Minister for Germany from 1938 onwards]. My single, most successful political effort was as follows: von Ribbentrop’s son took to arriving at Westminster, which is about 1,000 years old and has lots of stone arches, in two plum-coloured Mercedes Benz motorcars.

The object of the two cars was so that the two chauffeurs can get out and make a triumphal arch and say “Heil Hitler!” I got the boys who lived outside the school to arrive 20 minutes earlier and we used to greet this every morning with tremendous laughter and cries and whistles and everything. It got out of hand and became a famous event in London and I got summoned and I was told that it was an insult to a “friendly power.”

So I had a little bit of trouble talking to the headmaster about the Nazis being a friendly power. But in the end, I realized that he always got everything wrong and I said, “do you realize that the German Embassy cars are painted the colour of the royal family’s cars, which are all purple?” He said, “My dear boy, why didn’t you tell me before?!” and sent off an absolute sizzler to the ambassador saying this was outrageous.

UN News: That was your first brush with international diplomacy?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Absolutely, and it was successful too – unlike most of the others!

UN News: The late 1930s were a heady time with the dark clouds of World War II starting to gather. What comes to mind when you look back on your time at Oxford University?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Well, we spent most of our time demonstrating in one way or another. I nearly joined the Oxford Communist Party in 1937 because it seemed to me that – this was before the Soviet show trials – the Soviets had done a better job of looking after the people of the Soviet Union. But I very, very soon lost… well, I giggled during the briefings, so that did it. It was called “bourgeois dilettantism” and I was shot out – that was good. But then, we were also demonstrating about Ethiopia – Abyssinia, rather, as it was called back then – as well as the Spanish civil war, the total failure to react to Hitler and the persecution of the Jews.

During Operation Market Garden, Allied soldiers move past a knocked-out German 88mm gun near a bridge over the Meuse-Escaut Canal in Belgium. Photo: No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit

During Operation Market Garden, Allied soldiers move past a knocked-out German 88mm gun near a bridge over the Meuse-Escaut Canal in Belgium. Photo: No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit

UN News: “Teach us, good Lord, to serve thee as thou deservest; To give, and not to count the cost, to fight, and not to heed the wounds, to toil, and not to seek for rest, to labor, and not to ask for any reward, save that of knowing that we do thy will.” You wrote that even though you are not religious, these words drilled into your mind during your time at Westminster have provided you comfort in times of stress. How so?

Sir Brian Urquhart: I think it is the most brilliant description of something you ought to try to live up to – it’s the Jesuit prayer. The fact that one fails all the time is neither here nor there. You know, if you have an idea that there’s an enormous good in humanity and you need to do your best to help that along – well, that I suppose is a sort of religion in a way, it’s a faith anyway – and if you want to know how to do it, then that’s a very good prescription.

In 1939, in the wake of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s announcement of war against Germany, following its failure to respond to the ultimatum over Poland from Great Britain and France, Sir Brian went to a recruiting office and signed up to join the navy. Ten days later he discovered that the papers he had signed were not for the navy – they were for the army.

US troops that landed behind German lines in Holland examine what is left of a glider damaged during the airborne operation. Photo Courtesy of US Army

US troops that landed behind German lines in Holland examine what is left of a glider damaged during the airborne operation. Photo Courtesy of US Army

UN News: What impact did not joining the navy have on your life?

Sir Brian Urquhart: I evidently had too much to drink for lunch and I got the wrong form! I had a kind of romantic idea that the navy was the thing to be in, but it didn’t really make much difference. I was happy to be in anything by that time. In September 1939, one just felt that, you know, we were in such a pathetic position in comparison to Nazi Germany militarily, that the sooner one got into something as such the better, because if everybody did that we might have a hope in the end… I’ve always wondered how it was that we managed not to lose the war in 1940 – I think we should have, but we didn’t.

Sir Brian was ordered to report to the 164th Officer Cadet Training Unit at barracks in Colchester, before joining the Dorset Regiment as a second lieutenant and being posted to its 5th Battalion in the town of Frome in Somerset. In 1941, after time spent on home guard duties, which included surviving the sinking of a minesweeper escort while on patrol and a dive-bombing attack while having lunch, Sir Brian was asked to be an intelligence officer with the newly-formed Airborne Forces, which aimed to develop the British Army’s parachute and glider-borne troops.

British paratroopers moving through a damaged house in which they had sought shelter amidst the combat of Operation Market Garden. Photo: Army Film and Photographic Unit

British paratroopers moving through a damaged house in which they had sought shelter amidst the combat of Operation Market Garden. Photo: Army Film and Photographic Unit

UN News: The use of airborne troops as a fighting force was still in its infancy, with old airplanes and fairly rough training involved at that stage in its development. You have said that, deep down, you actually hated jumping out of airplanes. Yet, it led to a chance meeting with General Dwight 'Ike' Eisenhower when winds dragged you and other parachutists through a line of VIPs. What happened?

Sir Brian Urquhart: It was a big eye-opener for me. Eisenhower then was a completely unknown major-general. He was the first general officer of the United States to arrive in England.

Churchill wanted to display what the London Daily Mail insisted on calling “Britain’s airborne might” – which was about 2,000 somewhat disoriented people like me jumping out of very old aeroplanes, obsolete bombers in fact.

Everything was so weird in those days… what I reckoned without [was that] I was carrying two carrier pigeons in a cardboard carton around my neck, because they were our form of communication – we didn’t have radios because radios had all these valves and everything, and we couldn’t carry them in those days, it was not possible.

We [Sir Brian and other parachutists] went straight through the line of [watching dignitaries] and then I managed to disengage from my parachute and I couldn’t think what, so I stood up and saluted. The British were all furious. They said “bloody poor show” and that kind of thing, as if it was my fault that the wind was blowing at 45 miles an hour!

The general came running over. He said, “Are you alright, son?” I said yes. He said, “Why are you jumping in this wind!?” I said, “General, it was all laid on.”

And then he said, “What on earth is that thing around your neck?” I pulled one of these damned pigeons out and I said “this is to communicate to our headquarters that we’ve dropped safely.” I threw it in the air. The pigeon had definitely been air-sick because it fluttered to a nearby bush and sat there, looking at me and General Eisenhower with that awful way pigeons have and occasionally making rather awful noises and I burst out laughing – it was too much. And the general burst out laughing and then said, “I think the United States will have to do something about your communications” and left.

I never met him again, but what a guy! Everybody else was muttering about jolly poor show – it was sort of wonderful, very refreshing.

Sir Brian’s parachuting came to end in August 1942, when his parachute failed to open properly during a training jump. His plummet to the ground left him with broken bones, compacted vertebrae and internal injuries. Asides from agonizing pain, his recuperation included being found to have no pulse following three separate, unrecorded and maximum doses of morphine during a hospital transfer; and, being immobile, except for his head and arms, during months spent on his back and head down in a traction bed positioned at a 30 degree angle. After months spent convalescing, he returned to the Airborne Forces in April 1943.

UN News: Your extensive injuries didn’t make you want to reconsider returning to the Airborne Forces?

Sir Brian Urquhart: It made me want to go back! I was absolutely heartbroken because I thought I was going to miss one of the main events, which was actually the Dieppe Raid [a 1942 Allied forces attack on the German-occupied port of Dieppe in northern France], which was one of England’s best and most total disasters. I was quite lucky to miss that. But no, I was interested in getting back to it.

As a junior officer, Sir Brian was involved in helping plan Operation Market Garden – one of the largest airborne battles in history. Taking place in September 1944, the operation involved British and American airborne troops capturing key bridges at Arnhem, Nijmegen and Grave in the Netherlands, as part of a push to bring the war in Europe to a quick end. Sir Brian considered the plan to be “strategically unsound,” with the landscape where the parachutists landing in intersected by canals and causeways which would make support from relieving ground forces difficult to obtain. His views led to his being left out of the operation’s execution on medical grounds.

The first session of the United Nations General Assembly opened on 10 January 1946 at Central Hall in London. Here, Secretary-General Trygve, speaks at his installation ceremony. (2 February 1946) UN Photo/Marcel Bolomey

The first session of the United Nations General Assembly opened on 10 January 1946 at Central Hall in London. Here, Secretary-General Trygve, speaks at his installation ceremony. (2 February 1946) UN Photo/Marcel Bolomey

In his autobiography, Sir Brian wrote how the operation ended up with “more than 17,000 Allied soldiers killed, wounded or missing in nine days of fighting, no possible reckoning of civilian casualties, and all for nothing or worse than nothing.”

Since the end of World War II, there has been some controversy over the battle and its failure to succeed in its objectives.

Sir Brian was portrayed in the well-known 1977 film 'A Bridge Too Far,' based on the operation, although his name was changed to Major Fuller in order to prevent viewer confusion due to another personage with the same name of Urquhart.

UN News: How did Operation Market Garden affect you personally?

Sir Brian Urquhart: This was a hugely ambitious proposition. It had the most number of aircraft ever put into the air at one time, dealing with parachute tugs, fighter escorts and bombing sorties. It was, I forget, five or six thousand aircraft – it was enormous, it had never been done before.

The Germans had learnt not to do it in Crete. The Germans thought Crete was a disaster, even though they won, because they killed so many of their own people. And this was exactly what we did. I was certainly mindful of Crete when we were planning that operation.

Well, I’m sorry to say… before Market Garden, I was fairly arrogant, fairly opinionated and had great confidence in the higher authorities. After that, I lost all of these feelings. I thought I had not handled it very well, in persuading them to change the plan, which I failed to do. I certainly was not impressed by the British generals involved, mostly General (Bernard) Montgomery, who came into this plan out of the blue to finish the war in one fell swoop.

Any fool could see that it wouldn’t work – but we won’t go into that now, it’s very long. I just felt very badly that I had not managed… I was 26 years old and it was extremely unlikely that I was going to turn over a plan which had been approved by Churchill and (US President Franklin Delano) Roosevelt and everybody else.

Given his stance on Operation Market Garden, Sir Brian was shortly afterwards posted out of the Airborne Corps – at his request – and joined the chemical warfare branch of 21 Army Group Headquarters, then located in Brussels.

There, he was assigned to the newly established 'T' Force, set up to accompany advancing Allied troops into Germany and secure strategic intelligence assets such as industrial plants, laboratories and eminent German scientists. In this role, Sir Brian happened to be one of the first Allied troops to liberate the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in north-western Germany.

Towards the end of combat operations in Europe, Sir Brian discovered that because of his young age but long service, he could not be transferred to the theatre of operations in Asia and faced little chance of being demobilized soon.

Thanks to renowned historian Professor Arnold J. Toynbee – whom Sir Brian knew after having attended Oxford University with his son Philip – Sir Brian managed to secure a transfer to the Foreign Office Research Branch in London, which Professor Toynbee headed during the war.

Professor Toynbee recalled that Sir Brian had once spoken of his pre-war ambition to work for the League of Nations and told him that a friend of his – Gladwyn Jebb, a British civil servant and diplomat – had been appointed the Executive Secretary of the Preparatory Commission of the United Nations and was now recruiting.

Sir Brian lost no time in visiting Mr. Jebb, who soon appointed him as his private secretary – in the process becoming the United Nations’ second recruit.

Meeting in London between 16 August – 24 November 1945, the Preparatory Commission was charged with setting up the new body in accordance with the UN Charter, which was signed on 26 June 1945 in San Francisco, and came into force on 24 October that year.

Following his service on the commission, Gladwyn Jebb went on to serve as Acting UN Secretary-General from October 1945 to February 1946, until the appointment of the first Secretary-General, Trygve Lie.

UN News: As a child, you had dreamed about working for the League of Nations. You managed to become one of the first staff members of its successor, the United Nations. How did you feel about that?

Sir Brian Urquhart: I felt fantastically lucky. In the first place, it was literally three weeks after I got out of the army, thanks to Arnold Toynbee. I was working for a superb person to learn from: Gladwyn Jebb of the British Foreign Office, who was the Executive Secretary of the Preparatory Commission. He was really the first Secretary-General and he was absolutely outstanding. So I simply sat back for six months and learned. I was lucky – incredibly lucky.

UN News: What was the atmosphere like during those early days of the United Nations’ birth?

Sir Brian Urquhart: This is what most of us had been waiting for, for six years, and suddenly one was lucky enough to be working for this new world organization.

A lot of people there had been much worse off than I was during the war. They’d been in the resistance in their own countries, had lost people in the war. It was a sort of bitter-sweet occasion in some ways. London was a mess. It was a very grey, dismal, bashed-about city – food rationing and all that. It was very un-cheerful physical surroundings, [but] the atmosphere at the UN was very upbeat. I mean, [the Soviet Union’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Ambassador Andrei Andreyevich] Gromyko was the life and soul of the party; he made these wonderful jokes all the time. He was 37 years old. We had an outstanding group of people. I mean, we had Adlai Stevenson from the United States, [and Edwin R.] Stettinius, we had Ernest Bevin from the United Kingdom, we had Gromyko from the Soviet Union… a very distinguished group and there were still more or less under the spell of San Francisco – more or less.

The euphoria of the early days soon changed as the rivalries of the Cold War started to make themselves felt. In his autobiography, Sir Brian wrote that “the statesmanlike attitudes of the early meetings soon gave way to competitive point-scoring, and on many critical issues the level of debate sank to name-calling, polemics, and abuse, rendering a positive outcome precarious if not impossible. In 1946 these depressing tendencies were only just becoming to become apparent.”

UN News: Given the excitement of those early days, how did it feel to see this change come over the still-forming organization?

Sir Brian Urquhart: It was a terrible shock, actually. I have to say that I and my contemporaries were on the whole rather naïve. We really thought that – since we’d had no civilian experience in our adult life at all – that if governments said they were going to change and to do things differently in the future, then they would. Of course they didn’t. We went right back to square one. In fact, worse than square one because we were in a nuclear arms race by 1948, which was extremely dangerous.

The New York City Building, at the old World's Fair grounds in Flushing Meadows, served temporarily as the location for the General Assembly between 1946 and 1950, until the completion of the UN Headquarters complex in Manhattan. UN Photo

The New York City Building, at the old World's Fair grounds in Flushing Meadows, served temporarily as the location for the General Assembly between 1946 and 1950, until the completion of the UN Headquarters complex in Manhattan. UN Photo

The UN was a very cynical organization by that time. The Russians had “excommunicated” Trygve Lie over Korea. They wouldn’t talk to him. The McCarthy people [investigators looking into claims of Communist spies and sympathizers in the US federal government and elsewhere, as voiced by people such as US Senator Joseph Raymond "Joe" McCarthy] were running around the [UN] Secretariat trying to nail all the American members of the Secretariat as communists, which was very depressing, because people were frightened of them. A lot of people simply lost their jobs for no reason whatsoever. And I was disgusted by that. I thought it was terrible. And it was all very well for me to be supporting them, but it didn’t help very much – well, we could go into that at great length, but we won’t.

I actually became very sceptical about the UN at that point and then I, unfortunately, had a rather considerable disagreement with the first Secretary-General, whose personal assistant I was – we had a temperamental disconnect, we didn’t fit well together. And I left him in 1948 over various disagreements, including about the Middle East. I really was in limbo for three or four years and was seriously thinking about leaving and then, miraculously, out of the blue, this young Swede arrived.