Interview with former UN official Brian Urquhart (Part 2)

Sir Brian Urquhart, who celebrates his 94th birthday in February, is a living chronicle of a large chunk of 20th-century history.

Throughout his four decades of service to the United Nations, starting as one of its very first staff members and ending as an Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs, he also helped shape history-making moments. He was present for the birth of the United Nations in 1945, and was witness to many of the Organization’s – and the world’s – seminal milestones.

All of these easily amount to a front-row seat on history. But Sir Brian’s links to history go even further. As a youth, his experiences include attending a lecture given by Indian independence leader Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi while in primary school and taking part in the coronation of King George VI.

I think I’d like to be remembered as an exemplary international civil servant – if there is such a thing. No, take out exemplary. As a good international civil servant, because I think it’s very important.

As a soldier in World War II, he was involved in the surrender of German scientists working in nuclear research; he was one of the first Allied troops to liberate the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp; and he even helped Danish author Karen Blixen, of 'Out of Africa' fame, out of a predicament at the end of the war. To top it off, his role in 'Operation Market Garden' – one of the most well-known military actions of the later stages of the war – was immortalized in an epic film.

As Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said in a tribute message on the occasion of Sir Brian’s 90th birthday four years ago, “You have had an enormous influence on every Secretary-General. Even today, staffers everywhere seek to live up to your example. And you remain one of our wisest and staunchest advocates.”

Here, in the second installment of a two-part feature, UN News spotlights the experiences and views of Sir Brian throughout his decades of service with the world.

The then-Belgian Congo became an independent state on 30 June 1960, under the name of Republic of the Congo. Post-independence chaos, including an attempt at secession by the mineral-rich province of Katanga, led to a request for UN intervention, which the Security Council authorized over 13-14 July 1960.

“The violent interaction between the Belgian troops and the Congolese destroyed all hope of restoring calm and normality… We also had to help the new and totally inexperienced Congolese administration to take hold of the reins of government in a chaotic situation,” Sir Brian wrote of this perion in his autobiography.

Service in the Republic of the Congo was a hazardous assignment for UN staff. During the life of the United Nations Operation in the Congo (ONUC), there were 250 civilian and military fatalities.

Sir Brian’s first service in the African country was in 1960 as an assistant to Ralph Bunche, who was then serving as the Secretary-General's Special Representative in the Congo.

Ireland’s Conor Cruise O’Brien was then serving as the UN Representative in Katanga, but eventually left, partly due to threats against his life. In late 1961, Sir Brian replaced Mr. Cruise O’Brien in the sensitive position in the secessionist province.

Soon after his arrival in Elizabethville, as the capital of Katanga province was then known, Sir Brian was kidnapped and beaten by disaffected Katangese troops, coming close to being killed.

Thousands of soldiers from more than ten countries served with the UN Force in the Republic of the Congo, helping to restore order and calm in the country in relation to the breakaway province of Katanga. Here, a Swedish Army carrier crosses a bridge built by UN peacekeepers. (3 September 1963) UN Photo/BZ

Thousands of soldiers from more than ten countries served with the UN Force in the Republic of the Congo, helping to restore order and calm in the country in relation to the breakaway province of Katanga. Here, a Swedish Army carrier crosses a bridge built by UN peacekeepers. (3 September 1963) UN Photo/BZ

UN News: In the wake of Conor Cruise O’Brien’s departure from the post of UN Representative in Katanga, you said that it was a job that no one in their right mind would have wanted. Yet you took it. Why?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Well, there wasn’t any way that I wouldn’t take it! I was asked to take it by Ralph Bunche, who was my boss and in whom I had enormous confidence. We were in a hopeless mess at that time. The morale of that whole force had completely gone to bits. And we’d had to take Conor Cruise O’Brien out because he was in physical danger of being seriously damaged – and there wasn’t any way that you could say no. I wouldn’t have dreamt of saying no. I got kidnapped the second night I was there, actually, which was unfortunate.

UN News: In your kidnapping, you were alone and far from any help. How did you save yourself? Did that experience shake your faith and dedication to the UN?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Not at all! On the contrary, it made me anxious to get back and try to fix the situation. I was lucky because the colonel of the Gurkhas [serving as UN peacekeepers], S.S. Maitra, who was my great friend, was a fantastic soldier. The Gurkhas had this unbelievable reputation in Katanga. They were supposed to be able to cut people’s limbs off in mid-air with their kukris [a machete-like knife used by the Gurkhas], this kind of thing, but they were wonderful soldiers. So I really survived by saying, “You can kill me – but don’t think the Gurkhas will not come and get you if you do it.” Actually, since nobody had the foggiest idea where I was, it wasn’t true, but nonetheless it worked. And I really think it’s what saved me.

A view of some of the refugees and the make-shift living quarters outside the city Elizabethville. (8 September 1961) UN Photo/BZ

A view of some of the refugees and the make-shift living quarters outside the city Elizabethville. (8 September 1961) UN Photo/BZ

Throughout the first decades of the UN’s existence, Sir Brian worked very closely with Ralph Bunche, an academic who had been active in the US civil rights movement and had been working in the US State Department when Secretary-General Trygve Lie had him come to the UN to oversee the Department of Trusteeship. He was awarded the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize for his mediation work in the Middle East. The two colleagues became close friends over the years. In addition to penning a biography of the UN’s second Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjöld, Sir Brian also wrote a biography of Mr. Bunche.

UN News: Your link to Dag Hammarskjöld is quite well known, perhaps more so than your ties to Ralph Bunche. Can you tell us about Mr. Bunche and his impact on the UN?

Sir Brian Urquhart: I first met Ralph Bunche just when I got into the Preparatory Commission in London in 1945. I was still in uniform because I didn’t have any civilian clothes. I remember my wife and I took him to the London Zoo on a Sunday because he didn’t have anything to do. I didn’t know it, but he was already a famous figure in the United States.

He was the original writer for what is now the civil rights movement. He had conducted, along with a few other people, a number of very successful, original civil rights demonstrations. He had written the first draft of An American Dilemma [full title: An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy] which is still the classic work on the problem of the negro in the United States. He was very modest, so he would never tell you he’d done anything. He was incapable of blowing his own horn, which is terrible. So I didn’t know any of this. And then, time went by and when [the UN’s second Secretary-General Dag] Hammarskjöld arrived, he took Ralph into his own office.

When I joined Ralph, I became his chief assistant. He was what was called the Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs [one of two officials in that role]. At that time, he had just got the Nobel Peace Prize for the armistice agreements in Israel and the five Arab states.

He was a very, very famous person and he didn’t like it. He wanted to go back to Harvard where he was a professor and kept on saying he was going to do it, but had just one more thing to do. And then Israel declared statehood and he was immediately sent to the Middle East to try to umpire the 1948 war between the Arabs and Israel. He became – when [Swedish UN mediator Count Folke] Bernadotte was assassinated – the mediator and produced this fantastic result. Ralph was a really, absolutely remarkable person, and he became my closest friend, as a matter of fact. That is the difference between him and Hammarskjöld… It took Ralph three years to get used to anybody and those three years were spent in testing you, by giving you really impossible things to do and then tearing up whatever you wrote or said or suggested as a result, and starting all over again. And if you got through that, you were in! And I realized this, fortunately, so I enjoyed it.

And I must say that we had a wonderful 20 years. Ralph, after Hammarskjöld, probably deserves more than anyone else for establishing a standard of international [civil] service. He minded passionately about [the role of] an international civil servant, to the extent that the United States said that Ralph was always much more resistant to anything they suggested, more than that from any other country. And it was probably true.

He was determined to be independent. He was, like Hammarskjöld, an intellectual with a fantastic capacity for seeing round corners into the future, for having alternative courses of action, for never being caught flat-footed. And he was also totally honest. He would never, ever tell anyone something that wasn’t true, which annoyed people at first but then they discovered that it was quite good, because it worked both ways.

I would say that, in his own way, Ralph was one of the most extraordinary people I have ever met and he taught me everything I know about politics and international affairs. He was absolutely remarkable and I wish that he was more remembered than he is. But that was hopeless. For example, Ralph wouldn’t allow anybody to publish that he’d written the first draft of An American Dilemma.

He tried to turn down the Nobel Peace Prize, which upset the Norwegians, but then they got Trgve Lie to order him to take it. I mean, he thought this all interfered with doing the job – the job was it. It wasn’t you. And everything you had went into that and anything that distracted was out, like good public relations or flattery or anything like that. He was a very remarkable person and also, personally, one of the most delightful, funny… he was a marvellous fellow.

Sir Brian was instrumental to the development of UN peacekeeping. As the Suez crisis of 1956 unfolded, the idea of a UN force was discussed by Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld and Lester Pearson of Canada, who headed the Canadian delegation to the UN from 1946 to 1956, and served as President of the General Assembly’s seventh session.

Mr. Pearson proposed and sponsored a resolution which created the United Nations Emergency Force – the UN’s first deployment of peacekeepers – to police the area involved. Sir Brian, one of the few people with extensive military experience within the UN Secretariat’s political offices, was heavily involved in assembling this first ever UN peacekeeping deployment and its subsequent development as a tool in international relations.

In his autobiography, he wrote that “the real strength of a UN peacekeeping operation lies not in its capacity to use force, but precisely in its not using force and thereby remaining above the conflict and preserving its unique position and prestige. The moment a peacekeeping force starts killing people it becomes a part of the conflict it is supposed to be controlling, and therefore, part of the problem. It loses the one quality which distinguishes it from, and sets it above, the people it is dealing with.” In 1988, the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded the 1988 Nobel Peace Prize to UN Peacekeeping Forces, noting that through their efforts they have made important contributions towards the realization of one of the fundamental tenets of the United Nations.

In addition, peacekeeping was the part of his job that Sir Brian loved more than any other and he felt a strong rapport with the 'blue helmets,' as UN peacekeepers became popularly known.

“Although, as their civilian chief, I had often had to prod or to restrain them, we had had, on the whole, the happiest of relationships, and I was very sad to leave them,” he wrote in his autobiography.

UN News: You were there for the birth and later development of UN peacekeeping operations in various locations. Some of those – like in Lebanon and Cyprus – are still there, decades after they started. What do you say to criticism that these are examples of how peacekeeping is not bringing about a peaceful conclusion to conflict?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Peacekeeping was never...a peaceful conclusion, it was for making the conditions for a peaceful conclusion. And if you had something like Cyprus, where the Cyprus problem is sort of national industry and sport by now, on both sides, it’s very difficult to do.

The question is whether it’s better to have Cyprus held in a state of more or less equilibrium but not solve the problem, or just getting out of there and letting the two sides fight it out, in which case the Greeks will lose. And I think that it’s no question, we have to stay there. The most amazing example of this is the [UN] observers in Kashmir, who the Indians would like to get rid of, [and] the Pakistanis will never allow to, because they indicate the problem is not settled.

UN News: You have described a UN peacekeeping force “like a family friend who has moved into a household stricken by disaster. It must conciliate, console and discreetly run the household without ever appearing to dominate or usurp the natural rights of those it is helping.” Do you think peacekeeping has maintained that incarnation today?

Sir Brian Urquhart: This is what it was like in the Cold War, when we would try to stop regional conflicts from setting fire to the east-west nuclear conflict, which was very important, particularly in places like the Middle East and Africa.

It is changing now because the UN now does much more complicated civilian-military operations inside countries. We used to be on the borders, stopping conflicts between nations. They were mostly border conflicts from the period of decolonization .

Now we’re inside countries dealing with political, human rights, humanitarian problems of all kinds, including… I mean in the Congo, we were virtually running the government of the Congo in 1960; something we’d never done before. And I think that this is the form that peacekeeping is taking. Kofi Annan once said that the United Nations is the only fire brigade in the world which only buys a fire engine after the fire has stared. Think about it. It’s a good point.

UN News: Like many who have followed in your steps, you have experienced violence during your service as a UN civilian peacekeeper. What do you make of the growing targeting of UN peacekeepers whereas once they were widely considered neutral players in a conflict?

Sir Brian Urquhart: This is very serious. You used to get shot at quite bit, but at least you weren’t officially targeted by a highly effective terrorist organization. I think this is a disastrous thing – I don’t know what can be done about that…

If you fortify all the UN headquarters, the UN people have less and less contact with the people they’re trying to help and then their performance will go down. For what it’s worth, our great good fortune was that you could walk out the door, wander down the street and talk to people. You can’t do that now and that, I think, is a very, very serious problem for anyone trying to help.

On the Security Council, Sir Brian wrote that “… as one who had watched the Security Council from the beginning I sometimes felt that only an invasion from outer space would be a sufficiently non-controversial disaster to bring the Council back to the great power unanimity that the Charter required in order to make the United Nations effective.”

UN News: What is your view on calls to reform the Security Council, on the grounds that it no longer represents the world we live in?

Sir Brian Urquhart: I think it’s terrible, but this is the problem of regional identity, isn’t it? Because if you’re going to have the Security Council more representative, you’re going to have to possibly have a permanent regional representative for each region, but who is the top [one] in each region? Nobody knows. Not in Latin America, not in Africa. For Asia, they’ve already got China but then there’s Japan. It’s a very complicated problem and unless they make it much, much larger, which I think would be probably very inefficient… I don’t know who is going to solve that. I don’t know what the solution to that is. People have suggested all sorts of complicated solutions, but they’re too complicated.

What you have to hang on to is the Council’s feeling that it has a serious mission which is over and above what nationality you are. If you can only get that – and I think to some extent it does have that now – I think a lot of the give or take on these recent so-called Arab Spring problems and problems in Cote d’Ivoire have had the makings of a kind of corporate responsibility in the Council itself, for actually trying to do something. That’s good. You couldn’t do that in the Cold War. It was impossible.

UN News: What role do you see for the UN in the 21st century, especially compared to when it first began in the late 1940s?

Sir Brian Urquhart: I would like to see it as a much more international organization than it is now. I mean, I think it’s nice for governments to be taking the initiative in the Security Council, for example, that’s fine. And they’re actually doing some very interesting stuff now with the responsibility to protect and everything.

I would like to see a much more solid international leadership, which would really look at problems which are going to affect the future completely. I already mentioned the so-called global problems like climate change and global warming, and certainly some of the effects of the population and communications revolution. I think the UN does have a huge role to play there, quite apart from its role in peace and security which I think it is making progress on.

I still think that the UN needs to have a standing establishment to do emergency things – at least a core establishment for peacekeeping, a core establishment for humanitarian rescue and so on. It’s beginning to get there but hasn’t gotten there and until it does that, it’s going to be regarded as second-rate, which is bad.

I think that it’s absolutely essential to have at the top of the organization – and after all, the Secretary-General is the only person chosen by all the members – you really need to have someone who is not only a leader, but an intellectual leader. And if governments don’t like that, they’ll get used to it. I mean, to look back to Hammarskjöld: Hammarskjöld’s first objection was to the American CIA coup in Guatemala – that was the first brush he had with a great power when he came to the office. The United States was furious. John Foster Dulles and Eisenhower: they were livid. But then they discovered that if you had somebody independent like that, he could go to China – with which they had no relations with – and negotiate 17 American airmen out of captivity because people in China knew the guy was independent!

This is what I would like to see … but we’re in different times now. And I think it would be a very great pity if the UN doesn’t play a much more active role in really getting after these long-term problems which governments often can’t face because they’re so busy with the short-term rigmarole that they don’t get ‘round to it.

Sir Brian was appointed Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs in 1974. The post had been vacant since the death of its previous holder – Sir Brian’s close friend and colleague, Dr. Ralph Bunche – in 1971.

“It meant a great deal to me to follow in Bunche’s footsteps, and I was also proud to have got to the top in the Secretariat under my own steam, instead of being a political appointee as most of my senior colleagues had been,” Sir Brian wrote in his autobiography. "What followed were busy years, particularly with events in Lebanon, Cyprus, the Middle East and Namibia."

In the wake of the UN’s 40th anniversary in 1985, Sir Brian decided it was time to retire. “Much as I loved the work and was dedicated to the organization, I had 40 years of fairly continuous pressure and enforced discretion, and I wanted a little freedom of action and speech before I got too old to enjoy it. I was also anxious to hand over in an orderly fashion to a properly designated successor,” he wrote.

UN News: You have had a very unique position in being able to observe Secretaries-General, from up close and afar, for all of the United Nations’ 66 years. In brief, your thoughts on Trgve Lie, the UN’s first Secretary-General?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Well, Trygve Lie, you know, actually says in his memoirs, “Why has this horrible job fallen to a labour lawyer from Oslo?” He was absolutely right. He didn’t want to be Secretary-General. He didn’t run for it. He wanted to be President of the General Assembly.

I liked Trygve very much. He was a very decent guy and if you think he did nothing, you’re now sitting in something he did do, which was to get the Headquarters. I mean, we were like the Flying Dutchman when we got to the United States; we were always moving from the gym in Hunter College to the gyroscope plant at Lake Success on Long Island, it was terrible. He got the UN settled in New York, which was absolutely essential. If we had gone and settled in some of those resort places that were offered, this organization would be dead. This is very important place to be. It’s a very abrasive hub of world affairs and that’s good for everybody.

UN News: Your thoughts on Dag Hammarskjöld?

Sir Brian Urquhart: I think Hammarskjöld was the most impressive international leader so far anywhere. He was quite remarkable and he was genuinely international and I think he was a person of some genius which has created this flame which is still running, more or less.

UN News: Your thoughts on U Thant?

Sir Brian Urquhart: U Thant was, in one way, the opposite to Hammarskjöld, but in a funny way, he was very courageous. It was U Thant who, during the India-Pakistan war – which was extremely serious because you had China, Russia and the United States involved – went there, and got it sort of put on hold. He took a very important initiative in the Cuban missile crisis, which I think greatly helped in the resolution of it. He never told anybody about it. But he also did something which nobody else did in the Cuban missile crisis, which was actually go to Cuba and sit on Castro’s head before Castro got something going, which really would have got the thing off to a nuclear start. I had a huge regard for U Thant. He was a Buddhist. He was a very highly moral person. He believed that it was more important than politics, which didn’t go down too well with diplomats. He was excellent. A good man.

UN News: Your thoughts on Kurt Waldheim?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Not my favourite Secretary-General, I have to say, but I also have to say that he was a dedicated worker – he worked like hell. I was running the peacekeeping business then and I must say that he was very supportive of what we did, and if you suggested a good idea to him, he would do his level-best to carry it out. And I think he got a very bad rap for all this business of denying he was in the German Army. It was a great pity. It did nobody any good. It was ridiculous. He didn’t need to do it.

UN News: Your thoughts on Javier Perez de Cuellar?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Javier, I think was much more effective than people ever realized. Like U Thant, he was a very quiet man at a very key period – after all, this was the end of the Cold War. It was very tricky. He was a cerebral person, he had very good people working for him. He was very, very good in dealing with the nightmare situation going on in the late 80s, and I think he will, in history, come out extremely well.

UN News: Your thoughts on Boutros Boutros-Ghali?

Sir Brian Urquhart: You know, Boutros Boutros-Ghali is somebody I knew very well before [he became the UN’s sixth Secretary-General]. He’s a brilliant, extremely likable, brilliant man – perhaps too brilliant for his own good in this kind of job. I don’t know how it was that he managed to become a factor in American electoral politics, but he did. They were determined to get rid of him. I think it was a shame, but I think he was a little too much of a prima donna to do this kind of job – and I say that as somebody who likes him very much. If you were going in to a competition on who you’d like to spend an evening talking with, then Boutros-Ghali would be right at the very top.

UN News: Your thoughts on Kofi Annan?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Kofi, you know, came from the Secretariat, like me. I think he did a remarkable job and he became quite an important public personality – which was important. He was very articulate. He had very, very good people working for him. He started quite a few ideas, notably the responsibility to protect, which he actually introduced in a speech in the General Assembly long before it became a sort of a fashionable thing. And that led to all these people studying it and it actually being endorsed by the Millennium Summit. I think he did a wonderful job. I think he had a terrible time over Iraq, where he was honest. That was very difficult and he managed to run right into Washington, DC.

UN News: Your thoughts on Ban Ki-moon?

Sir Brian Urquhart: I’ve always made a principle of never publicly commenting on the serving Secretary-General. The serving Secretary-General has enough to do anyway without jokers like me making neat remarks about them, so I’m not going to do that!

Following his retirement, Sir Brian has devoted himself to writing on international affairs, including the United Nations. In an editorial earlier this year, The Guardian newspaper described Sir Brian as “one whose life is an allegory of international co-operation…He was the anti-bureaucrat: plain-speaking and even once criticised for keeping too small a staff... He is a rare argument for the unity of the virtues and a mark of what the UN could and should be. He says sovereignty needs to be reconciled ‘with the demands of human survival and decency in the astonishingly dangerous world we have absentmindedly created.’ Governments should listen.”

UN News: In years to come, how would you like to be remembered?

Sir Brian Urquhart: I think I’d like to be remembered as an exemplary international civil servant – if there is such a thing. No, take out exemplary. As a good international civil servant, because I think it’s very important. Sooner or later, we’re going to have to develop it.

UN News: Looking back at your time at the UN, do you have any regrets about things that could have been done better?

Sir Brian Urquhart: If you were brought up as a Unitarian like me, you always have regrets! Of course, I think we could have done things better. But I’m not sure one needs to dwell on that too much. I think one has to dwell, when one gets old, first of all, on trying to leave something behind that’s of some use to other people. And I’ve tried to do that in by writing about Hammarskjöld, Bunche and indeed about myself, and also in a whole number of books on trying to reform the UN – which nobody has ever read, but that’s alright.

I think one needs to do that. It’s like what you say to people; you always think [afterwards] of something you might have said which was infinitely smarter. It’s the same in life. After the fuss has died [down] and you’ve somehow managed to muddle your way through some problem; you think, “God damn it, if only I’d thought of… !” or “If I’d just thought of so and so, he would have been just the person.” But it doesn’t happen like that.

UN News: What’s it like to be considered a living legend in international affairs and a link to a different time, or so many different times, in the UN’s history?

Sir Brian Urquhart: Well, in the first place, I’m very sceptical of remarks like this “living legend” business. Everybody’s a living legend to somebody! I mean, come on! I don’t want to be thought of as just a relic from an ancient time – although, I must say, sometimes I slightly feel that – but I think we all put our little footprint in the sand, and sometimes we push forward a plank to build a bridge to whatever it is in the future and all this stuff that people say in obituaries. You know, that’s nice, if you can do that. I would have loved to have been Picasso or something like that, but I wasn’t. I had a wonderful time working for the UN. It was quite difficult sometimes, but it was what I wanted to do. I was incredibly lucky in who I worked for and I was incredibly lucky in the jobs that I was given. You can’t really fault that. I don’t know that I had much to do with that, I was just very lucky. I loved the job, I believed in it. I still believe in it. What’s more fun than serving an organization like the UN?

Trygve Lie. UN Photo

Trygve Lie. UN Photo

Dag Hammarskjöld. UN Photo/ES

Dag Hammarskjöld. UN Photo/ES

U Thant. UN Photo/Yutaka Nagata

U Thant. UN Photo/Yutaka Nagata

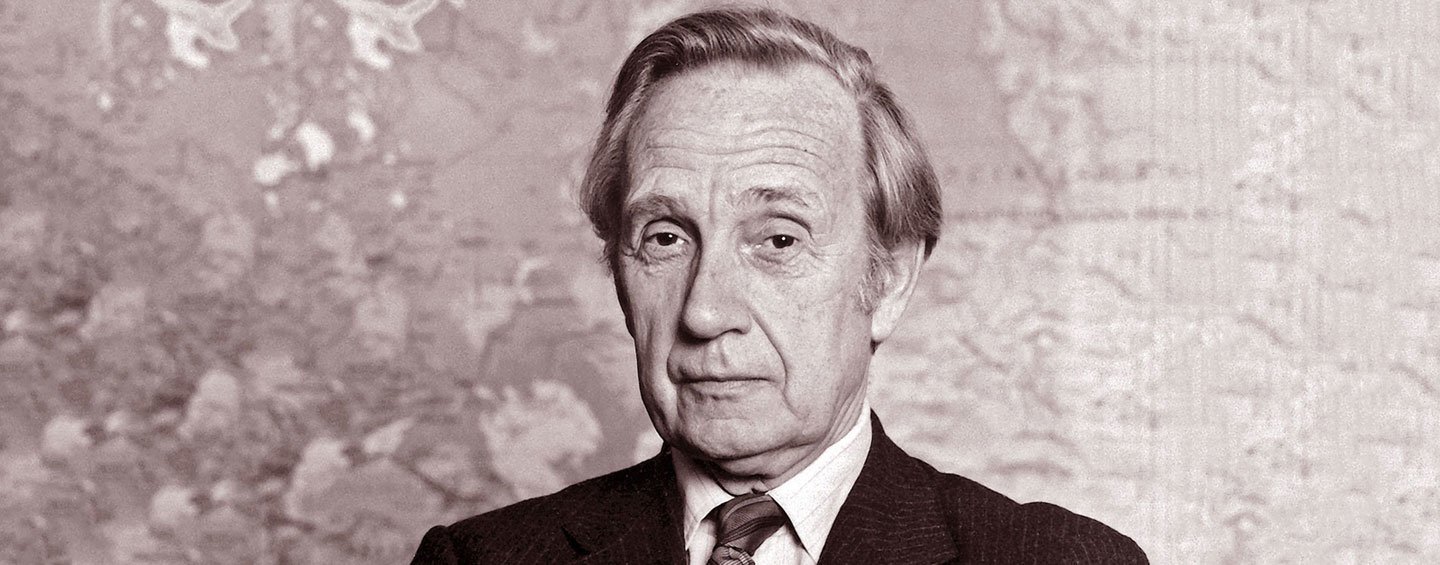

Kurt Waldheim. UN Photo/D. Burnett

Kurt Waldheim. UN Photo/D. Burnett

Javier Perez de Cuellar. UN Photo/Backrach

Javier Perez de Cuellar. UN Photo/Backrach

Boutros Boutros-Ghali. UN Photo/Milton Grant

Boutros Boutros-Ghali. UN Photo/Milton Grant

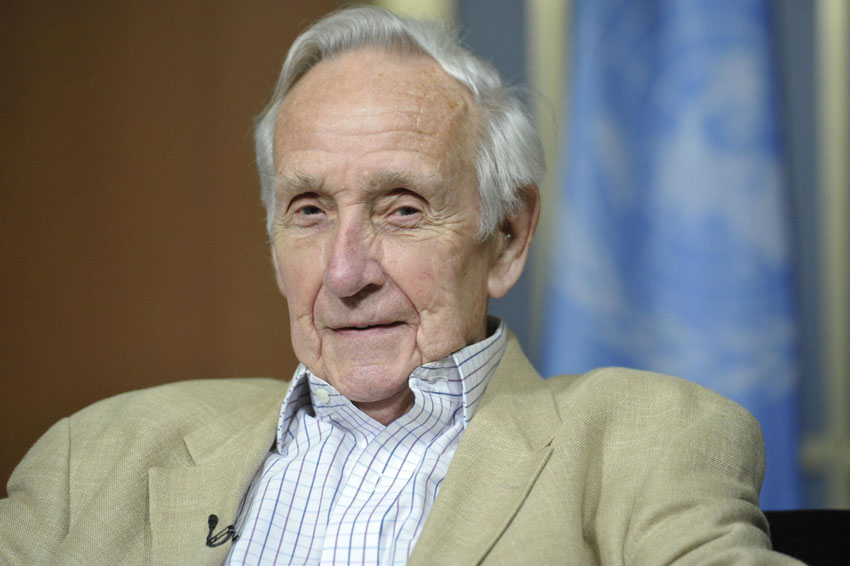

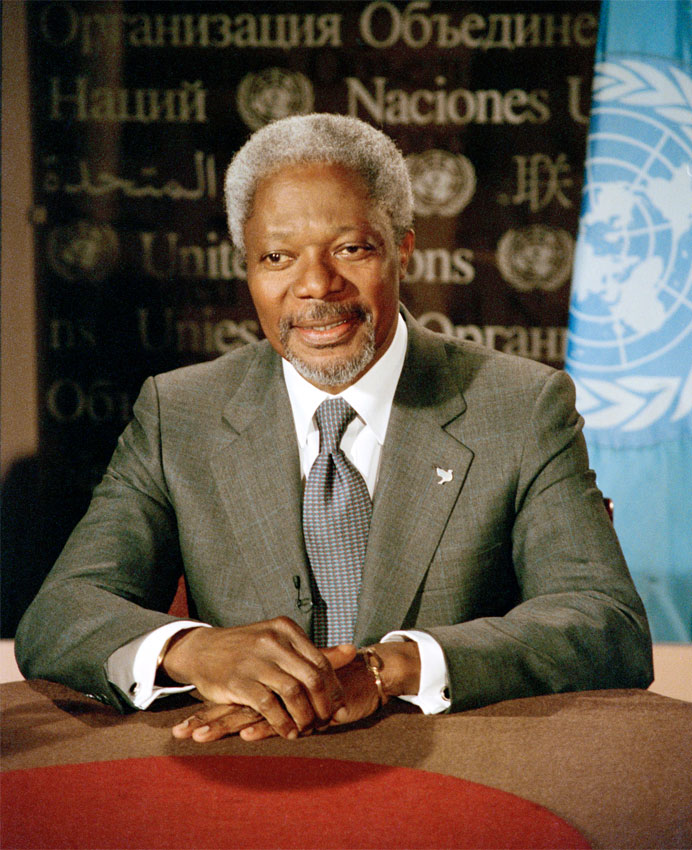

Kofi Annan. UN Photo/John Isaac

Kofi Annan. UN Photo/John Isaac

Ban Ki-moon. UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe

Ban Ki-moon. UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe